Aftermath: Art in the Wake of World War One, Tate Britain review - all in the mind | reviews, news & interviews

Aftermath: Art in the Wake of World War One, Tate Britain review - all in the mind

Aftermath: Art in the Wake of World War One, Tate Britain review - all in the mind

Otto Dix’s prints at the heart of ambitious survey of British, French and German artists’ inter-war work

Not far into Aftermath, Tate Britain’s new exhibition looking at how the experience of World War One shaped artists working in its wake, hangs a group of photographs by Pierre Anthony-Thouret depicting the damage inflicted on Reims.

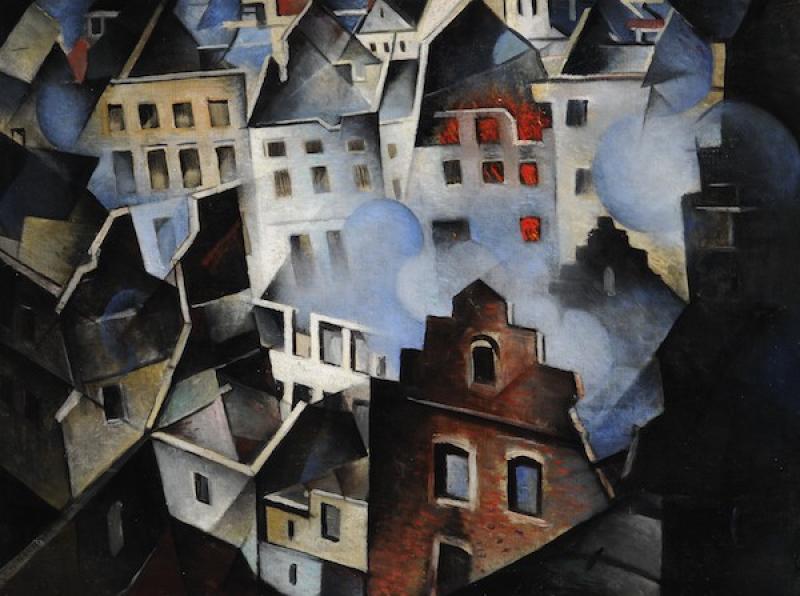

In one photograph the cathedral crouches like an abject creature, low and painful behind a foreground strafed with chimneys, gutters and bed steads poking like unseemly viscera from precarious slopes of bricks. Shutters hang in blind windows, their eyes blown out, dead. In another photograph, he looks up at the cathedral’s roof from the transept. The roof has collapsed in patches leaving vaulted arches intact but plastering blank patches of dull sky over soaring space carrying the memory of lost bricks. The impression is of a caved-in skull seen from the inside, madnesses crowding out the mental architecture. In its combination of unblinking honesty, psychological symbolism and stark metaphor it captures some of the divergent ways in which British, French and German artists responded to the unprecedented devastation of war, which this exhibition sets out to survey.

Clearly a survey of the art that grew from the interwar years is considered relevant in the present time of fractures and demagogues

Historically-focused exhibitions are strange beasts, hard to balance. Historical detail can overwhelm or under-embellish the art on display, which itself may end up as a strange congeries of unrelated pieces or a strict corral of overly-laboured points. Aftermath, which is ordered roughly chronologically and, according to Tate Britain Director Alex Farquharson, uses the war as “a lens by which to understand the key interwar period”, aims to present how the war shaped artists’ work, choice of subject matter, and their thoughts on what art could or should do. In that it brings together an impressive array of work from Britain, France and Germany which encompasses artists’ work in oil, stone, linocut and collage, and takes in along the way architectural plans, Michelin guides to the war-torn towns and postcards, the exhibition gives a broad overview of the post-war and inter-war period.

But with such divergent work, the message of the exhibition often takes precedence over the work – pieces’ individual complexities can be flattened as they are subsumed to a larger collective point. So the room dedicated to Surrealism and Dadaism is both clever (the Max Ernst corner shows the source material from a series of photocollages) and a little ungracious because the pieces’ collective point is to foreground technique over subject: collage and automatic painting are showcased because in a world of broken images they naturally become suitable means of representation. Another more general criticism is that the issue of differences in aesthetic heritage between artists from different countries feels thinly covered, even though it plays a crucial role in the way artists worked during and after the war.

But even if the pre-war context of these artists lacks body, the afterlife of (particularly German) works tracks an interesting path through the exhibition. Ernst Barlach’s bronze, The Floating One, 1927/1987 (pictured right) was presented to Gustrow cathedral as a memorial for the dead but later melted down by the Nazis (the moulds were not destroyed and the bronze hanging from the ceiling was cast from these in 1987); Georg Schrimpf’s Swineherd, 1923, is quite sickeningly sweet but was admired by the Nazis for its obvious derivation from the German Romantic tradition. John Hartfield’s photomontage After Twenty Years!, 1934, juxtaposes a line of skeletons hovering like spirits above ranked children bearing guns in military formation, a sad and sinister image.

But even if the pre-war context of these artists lacks body, the afterlife of (particularly German) works tracks an interesting path through the exhibition. Ernst Barlach’s bronze, The Floating One, 1927/1987 (pictured right) was presented to Gustrow cathedral as a memorial for the dead but later melted down by the Nazis (the moulds were not destroyed and the bronze hanging from the ceiling was cast from these in 1987); Georg Schrimpf’s Swineherd, 1923, is quite sickeningly sweet but was admired by the Nazis for its obvious derivation from the German Romantic tradition. John Hartfield’s photomontage After Twenty Years!, 1934, juxtaposes a line of skeletons hovering like spirits above ranked children bearing guns in military formation, a sad and sinister image.

Yet though the exhibition can feel overly dutiful, eddies of inspiration enliven the necessary pedestrianisms. While the room dedicated to memorials feels staid – if not drearily compulsory – its vitrine examines the warped ways people sought solace in an unrecognisable world. While official monuments focused in on anonymous men and mass memorial, the depth of individuals’ grief and bafflement caused them to turn to unorthodox means of quieting their losses. The photographs displayed were taken by Ada Deane who claimed they depicted spirits hovering above mourners gathered at Whitehall on Remembrance Day 1922. Such was their traction that before being revealed as hoaxes, many people had already come forward claiming to recognise their relatives’ spirits. It’s a reflection on how the deep weird calm after years of mass slaughter was just as strange as war. Whether war or peace was normal was no longer the question because all versions of reality were deeply strange.

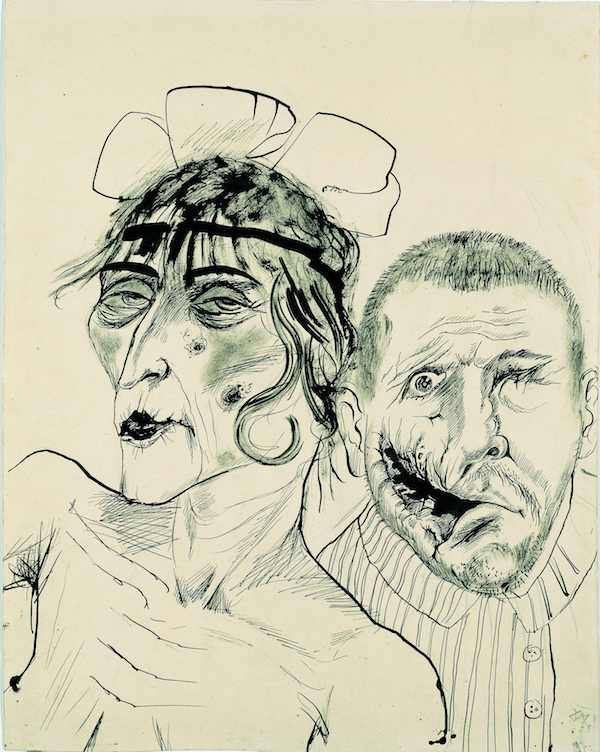

People, even, didn’t look the same. The purpose of portraits by surgeon-turned-artist Henry Tonks was to chart the effectiveness of innovative reconstructive surgery at Aldershot and Sidcup hospitals. The resulting portraits are not only touching but equally matter-of-fact about the disfiguring injuries permanently inflicted on each human subject. These men carried the war on their faces and in their bodies; each limp was a reminder of what could not be forgotten. And they carried the war in other ways too. Striking plaster sculptures by Marc Leriche and Louis François Carli of men suffering from episodes of mental trauma (respectively Astasia-abasia Psychogenic Tremor, 1917, and Sculpture of Soldier with Shell Shock, 1917) bear clear clinical witness to how psychological injuries took physiological form, contorting sufferers into grotesque shapes and fixed postures of fear. The terrors of the mind couldn’t be repressed so nor could they be denied – it’s as if reality had given reign to nightmare.

People, even, didn’t look the same. The purpose of portraits by surgeon-turned-artist Henry Tonks was to chart the effectiveness of innovative reconstructive surgery at Aldershot and Sidcup hospitals. The resulting portraits are not only touching but equally matter-of-fact about the disfiguring injuries permanently inflicted on each human subject. These men carried the war on their faces and in their bodies; each limp was a reminder of what could not be forgotten. And they carried the war in other ways too. Striking plaster sculptures by Marc Leriche and Louis François Carli of men suffering from episodes of mental trauma (respectively Astasia-abasia Psychogenic Tremor, 1917, and Sculpture of Soldier with Shell Shock, 1917) bear clear clinical witness to how psychological injuries took physiological form, contorting sufferers into grotesque shapes and fixed postures of fear. The terrors of the mind couldn’t be repressed so nor could they be denied – it’s as if reality had given reign to nightmare.

And to an extent this was more widely true, too: veterans were everywhere, begging, unable to work, mutilated. In some ways the War Widows, 1916, depicted by Dorothy Brett had it easier for losing their men than learning to live again with the tortured ghosts of the men they had once called their husbands. Artists were attuned to this gathering sense of interiority – particularly in Germany. Heinrich Hoerle’s lithographs Friendly Dream and Man with the Wooden Leg Dreams from his Cripple Portfolio, 1920, directly represent unconscious interior states by drawing on aspects of fairy tale but are clearly the result of deep commitment to social and political principles. Otto Dix’s War: Skin-Graft, 1924 likewise works on multiple levels. The etching depicts a man’s cranium – half of which has received a graft – nightmarish in its anatomical protrusions and protuberances; but it might depict his hellish whirling thoughts, or stand for the pain of the general experience of war. The individual here can stand for many. It’s this growing appreciation of individuals’ subjective mental experiences and the subconscious that recurs as a refrain later in the exhibition – greatly changed but still recognisable. In one corner, three landscapes hang at right angles to three female portraits (pictured above). Pastoral reflects personal: the landscapes address different ways in which a place might contain, express or heal the horrors it bears, while the portraits consider how women – marked too by the war, but differently from the men who fought – moved into modernity with new fashions, bearings, new psychological theories and types of work. The war changed things permanently. By 1925, women made up a third of the industrial, agricultural and administrative workforce in Germany and old class certainties had been given a stir; as Fernand Léger noted, “My new comrades were miners, labourers, artisans who worked in wood or metal. I discovered the people of France.”

It’s this growing appreciation of individuals’ subjective mental experiences and the subconscious that recurs as a refrain later in the exhibition – greatly changed but still recognisable. In one corner, three landscapes hang at right angles to three female portraits (pictured above). Pastoral reflects personal: the landscapes address different ways in which a place might contain, express or heal the horrors it bears, while the portraits consider how women – marked too by the war, but differently from the men who fought – moved into modernity with new fashions, bearings, new psychological theories and types of work. The war changed things permanently. By 1925, women made up a third of the industrial, agricultural and administrative workforce in Germany and old class certainties had been given a stir; as Fernand Léger noted, “My new comrades were miners, labourers, artisans who worked in wood or metal. I discovered the people of France.”

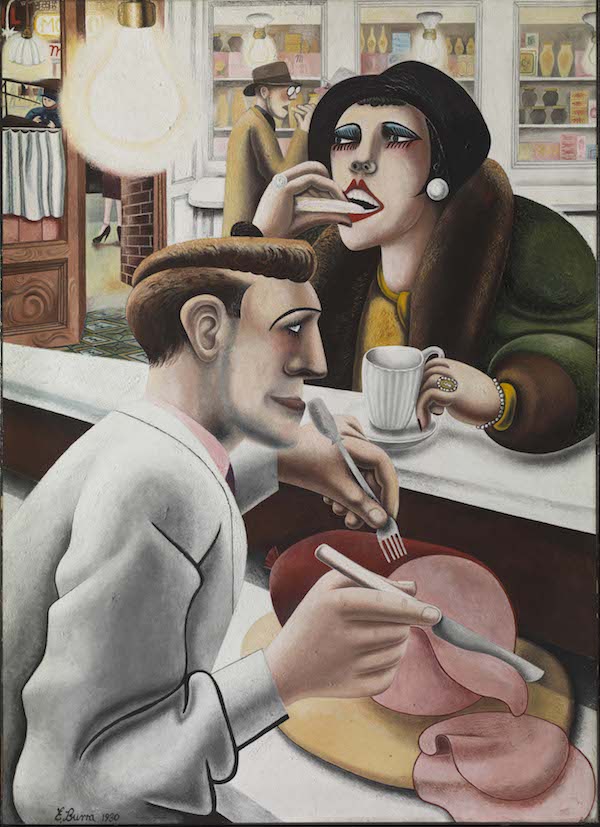

But perhaps the most potent way in which these new theories affected the inter-war years was in pleasure and entertainment. A portrait by Jeanne Mammen of Valeska Gert, 1928/9, a German Jewish artist whose experimental performances examined how the human body responded to sex, death, accident and orgasm, depicts her in an uplifting welter of pleasure, her throat long and face uplifted. Beneath tarantuline hair her eyes and brows are blissful black lines slicked across youthful skin. She’s surrounded by an excitement of gauze and wears a sexy clementine slip; she’s louche, embodied and ravishingly decadent. Nearby hangs Glyn Warren-Philpot’s Entrance to the Tagada, 1931-2, which affords us a glimpse into the Parisian cabaret, and Edward Burra’s The Snack Bar, 1930 (pictured above) in which a woman tucks with relish into a late-night snack while the waiter carves a decadent haunch of ham. Dancing, eating, loving and feeling to excess – in a word, hedonism. Why not when the end of the world had already happened?

But perhaps the most potent way in which these new theories affected the inter-war years was in pleasure and entertainment. A portrait by Jeanne Mammen of Valeska Gert, 1928/9, a German Jewish artist whose experimental performances examined how the human body responded to sex, death, accident and orgasm, depicts her in an uplifting welter of pleasure, her throat long and face uplifted. Beneath tarantuline hair her eyes and brows are blissful black lines slicked across youthful skin. She’s surrounded by an excitement of gauze and wears a sexy clementine slip; she’s louche, embodied and ravishingly decadent. Nearby hangs Glyn Warren-Philpot’s Entrance to the Tagada, 1931-2, which affords us a glimpse into the Parisian cabaret, and Edward Burra’s The Snack Bar, 1930 (pictured above) in which a woman tucks with relish into a late-night snack while the waiter carves a decadent haunch of ham. Dancing, eating, loving and feeling to excess – in a word, hedonism. Why not when the end of the world had already happened?

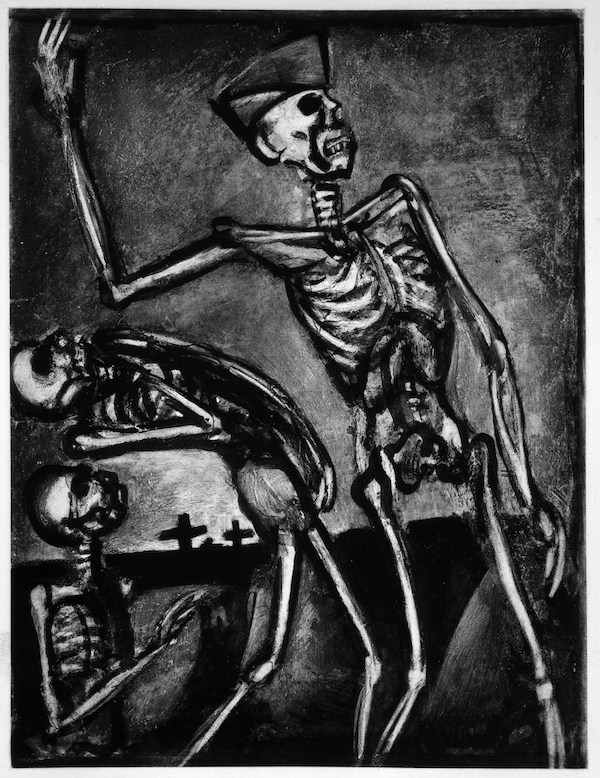

Beneath this hectic carnival remains threat. The swell of calm didn’t last long, and this is perhaps why the dark heart of the exhibition is a light-controlled room containing four print series, pyrrhic warnings against the repetition of horror on such a scale. Three line the walls (Max Beckman’s Hell, 1919; Käthe Kollwitz’s War, 1922; Georges Rouault’s Misery and War, 1927, pictured below) while Otto Dix’s magnificent print series War, 1924, takes up four vitrines set in a square in the centre of the room. The etchings draw from his own memories and, as a series, contain narrative possibilities that other pieces cannot. They move nimbly between registers – from realistic reportage to the deeply surreal – and for this they touch every aspect of the exhibition, from what happened on the battlefield to how people wanted to remember those years (and how they forgot them). Two depict without flourish, sentimentality or pity dead men up close; the ritualistic Dance with Death Year 1917 (Dead Man Heights), 1924, remains for all its gore carnivalesque; the fear graven into the eyes of pedestrians fleeing a street buzzed by a bomber is as direct as reportage photograph; while a moonscape of craters breaks into the gathered night, figureless and sterile.

Aftermath is an enormous, ambitious exhibition and clearly a survey of the art that grew from the interwar years is considered relevant in the present time of fractures and demagogues (there is free entry for veterans and serving members of the armed forces). Its weakness lies in its vast scope – which is also paradoxically its strength. Moving from room to room feels very much like moving from one argumentative point to another, but on the other hand this control allows for the exhibition to unfold itself in an easily-followed coherent manner. A theme returned to again and again, however, is how trauma on such a grand scale became the prompt for paying attention to the importance of the mind – how dramatically psychological states could insert themselves into the world because they are in fact part of it.

Aftermath is an enormous, ambitious exhibition and clearly a survey of the art that grew from the interwar years is considered relevant in the present time of fractures and demagogues (there is free entry for veterans and serving members of the armed forces). Its weakness lies in its vast scope – which is also paradoxically its strength. Moving from room to room feels very much like moving from one argumentative point to another, but on the other hand this control allows for the exhibition to unfold itself in an easily-followed coherent manner. A theme returned to again and again, however, is how trauma on such a grand scale became the prompt for paying attention to the importance of the mind – how dramatically psychological states could insert themselves into the world because they are in fact part of it.

This hits full force in Dix’s Nocturnal Encounter with a Lunatic, 1924. Behind the grinning skeletal figure welters a devastated landscape. Roof beams splay skyward as spatchcocked carcass ribs and the pale star of a dead man drapes over a deeply scored ground. Nothing is alive but the madman, and even that is doubtful, for his eyes are empty beads of light and this is his deadened mind’s landscape. This landscape is inflicted on Dix, who relays it and inflicts it on us. Decades on, people no longer carry this war inside them, but for the madman, this was no fleeting vision: this blasted landscape was the reality in which he lived. The horror is that war happened again, so soon.

- Aftermath: Art in the Wake of World War One is at Tate Britain until September 23

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment