Levit, LPO, Jurowski, Royal Festival Hall | reviews, news & interviews

Levit, LPO, Jurowski, Royal Festival Hall

Levit, LPO, Jurowski, Royal Festival Hall

Exhilarating gloom in the young Rachmaninov's First Symphony redeems hazy Scriabin

If Brahms’s First Symphony has long been dubbed “Beethoven’s Tenth”, then the 23-year-old Rachmaninov’s First merits the label of “Tchaikovsky’s Seventh” (a genuine candidate for that title, incidentally, turns out to be a poor reconstruction from Tchaikovsky’s sketches by one Bogatryryev).

The evening’s first half can be more quickly dispatched in words than it felt in performance, at least in the case of the piano concerto. Credit to Jurowski for programming an early work by Poland’s greatest composer before Lutosławski and Penderecki, Karol Szymanowski (funds available from the Polish Cultural Institute didn’t go amiss, either). His Concert Overture of 1906 sounds like a tone-poem in search of a programme. Its hero is no pale shadow of Strauss’s Don Juan, but has no comparably fine melodies to unfold, either, and careers towards the brass-heavy doominess of another, justifiably less well known Strauss protagonist, Macbeth, before the final victory flourishes. Jurowski plunged in with sharp-edged swagger, LPO horns rampant, but there was never a moment when this didn’t sound like imitation Strauss.

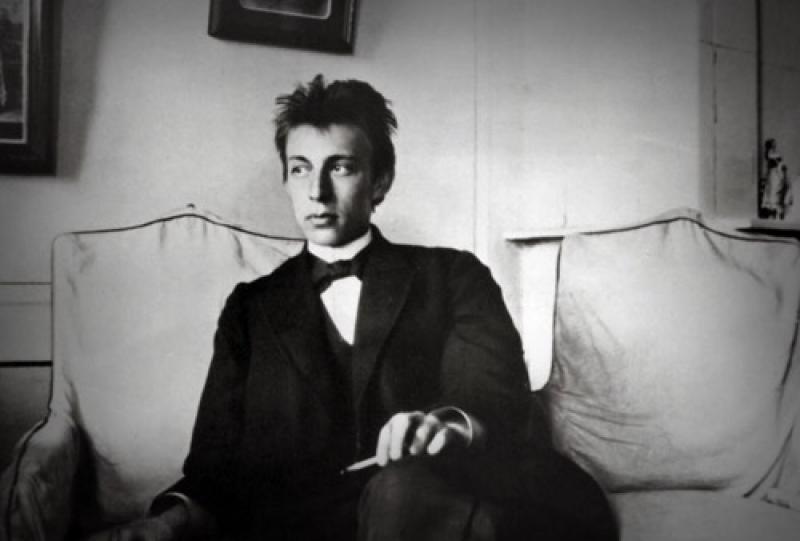

Previous live performances of Scriabin’s early concerto, premiered in exactly the same year as the Rachmaninov symphony (1897), left me with the impression of trim proportions and an unexpected virginal candour in the central theme and some of its variations. Those were beautifully introspective in the hands of the LPO strings, and Igor Levit’s subtle filigree could be heard here as it couldn’t elsewhere. The pianist (pictured below) came with glowing recommendations, but rarely did his contribution shine through, sounding more often like optional overlay; when the heavily-pedalled thunder did break out, it sounded approximate. The Bach encore felt mannered and glacial to me.

Enter blood and thunder again after the interval with the twists and Dies Irae-like descents of Rachmaninov’s opening. “Vengeance is mine, I will repay, saith the Lord” is the epigraph of both the symphony and of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina: I have my own fancy, kindly referenced in Andrew Mellor’s spot-on programme note, that we’re dealing here not only with Rachmaninov’s own Anna, Lodyzhenskaya, another married woman, but simultaneously with Tolstoy’s hectic heroine. Or so the feverish glitter and the careering towards catastrophe of the astounding finale, as exciting as the last of the Symphonic Dances at the end of Rachmaninov's life, would lead me to believe.

Enter blood and thunder again after the interval with the twists and Dies Irae-like descents of Rachmaninov’s opening. “Vengeance is mine, I will repay, saith the Lord” is the epigraph of both the symphony and of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina: I have my own fancy, kindly referenced in Andrew Mellor’s spot-on programme note, that we’re dealing here not only with Rachmaninov’s own Anna, Lodyzhenskaya, another married woman, but simultaneously with Tolstoy’s hectic heroine. Or so the feverish glitter and the careering towards catastrophe of the astounding finale, as exciting as the last of the Symphonic Dances at the end of Rachmaninov's life, would lead me to believe.

Whatever the impulse, the symphony is an astonishing technical display (how bizarre that Rachmaninov wanted it suppressed), a mining of only two themes which propel all four movements. And propulsion was the keynote here after a suitably dark and broad introduction which set up hope that was not to be disappointed for its hellish apotheosis at the end of the symphony. Peter Sparks’s clarinet kicked off full-toned woodwind which would dominate the languishing, feminine second subject and its painful extension, with Janacek-like oscillations, in the slow movement (hauntingly employed at length, incidentally, in a little gem of a Swiss film, Garçon stupide). Above all what kept ponderousness at bay was the focused tone of the brass ensemble, which now boasts possibly the best trumpets, trombones and tuba on the London scene. But there was exquisite lightness in the ghost-scherzo, too, rounded off with Jurowski’s masterly touch.

In the hair-raising peroration, the most effective and rounded tam-tam crashes I’ve ever heard – shades of Tchaikovsky’s “death” in his Sixth Symphony – fused gut-wrenchingly with orchestral groans. Like all the great Russian masters, Rachmaninov – with a “v”, please, not the French/American “ff” as this festival, perhaps due to its sponsors, insists – knows how to horrify and exhilarate at the same time. No wonder the younger members of the audience who are now so much a part of the LPO concert scene rose instantly to their feet.

- Next concert in the LPO's Rachmaninoff: Inside Out series is on 21 January (his one-act opera The Miserly Knight)

- Broadcast for the next month on the BBC Radio 3 iPlayer

rating

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Comments

Sounds like we should be

Sounds like we should be hearing Rachmaninov's First Symphony a lot more than we do (I've suppressed my American "ff"). Certainly, based on this review and my own small experience of Jurowski conducting, I'd love to hear it conducted by him. One speculation on the suppression of the symphony is that he couldn't bear to think about the disaster of its premiere, though you would know far better than I what the truth might be. If there's any truth to it at all, however, based on this report, it sounds like vengeance is certainly Rachmaninov's.