Mlima's Tale, Kiln Theatre review - simple, powerful tale about the rape of Africa | reviews, news & interviews

Mlima's Tale, Kiln Theatre review - simple, powerful tale about the rape of Africa

Mlima's Tale, Kiln Theatre review - simple, powerful tale about the rape of Africa

Lynn Nottage’s 2018 play gets an exquisite staging with moving performances

The work of the double Pulitzer-winning Black American dramatist Lynn Nottage has thankfully become a fixture in the UK. After its award-winning production of Sweat, the Donmar will stage the UK premiere of her Clyde’s next month, and MJ the Musical, for which she wrote the book, arrives in the West End in March 2024.

But not to be missed right now is her 2018 play Mlima’s Tale at the Kiln. Out of a magazine article about the ivory trade, Nottage has spun a Brechtian yarn of corruption and mendacity, minus the Verfremdung and with a surprising number of laughs, that suggests a whole world of illicit trading. It starts when two Somali poachers track Mlima in a Kenyan national park. Mlima has “seen 48 rains” and is one of the last “big tuskers" in the continent, hence a protected national treasure. What happens to this giant beast’s tusks traces a chain of corruption from the Maasai to a sumptuous apartment in downtown Beijing.

Reading the piece on the page, you sense that its impact is poignant enough: what director Miranda Cromwell and her set designer Amelia Jane Hankin have created onstage, however, will move many to tears.

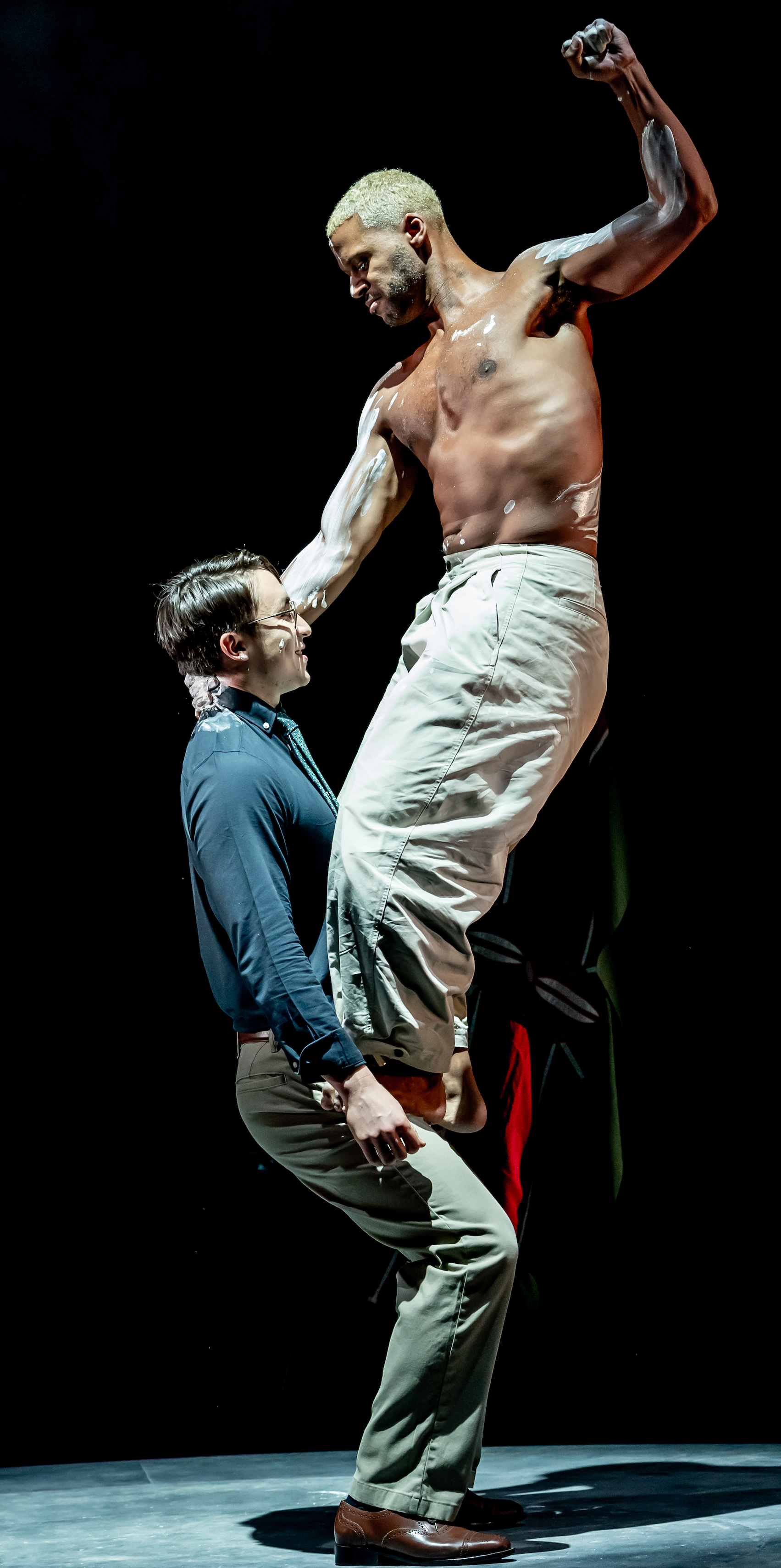

The first stage picture is a thin grey curtain, behind which can be seen the shadow of a tall figure. This is the actor-dancer embodying Mlima, Ira Mandela Siobhan, who emerges through the curtain, a regal bare-chested man with a sonorous voice, at home in the savannah though aware he is being tracked. When the poachers appear, the poison they shoot into his side starts to work, but they have to despatch him with an axe – an act no less shocking for being mimed.

These are poachers motivated by hunger. Geedi (excellent Natey Jones, in the first of six roles) is already concerned that they have killed the great beast known as “Mountain” and will be tracked themselves when they try to sell on the ivory. But their boss is a local cop, Githinji (Gabrielle Brooks), who will at least give them a good price for these exceptional tusks, they are sure.

But Githinji, too, is alarmed at their kill and mindful of how the spoils will be pursued. He promises the park warden, who has lost one of his prime tourist attractions, that the tusks will be given a respectful burial and the killers found; the two poachers are duly rounded up. The promise of respect is an empty one,

But Githinji, too, is alarmed at their kill and mindful of how the spoils will be pursued. He promises the park warden, who has lost one of his prime tourist attractions, that the tusks will be given a respectful burial and the killers found; the two poachers are duly rounded up. The promise of respect is an empty one,

The wheels of corruption turn round, from the bribable ship’s officer in Mombasa who puts the tusks on the manifest without the captain’s knowledge, all the way to the rich Beijing socialite looking for a “statement piece” for her new apartment.

Mlima is there throughout, a shadow warrior as he promised his beloved mate Mumbi. Siobhan is almost permanently onstage; he listens in on duplicity being plotted, bristles when lies are told, rises up imperiously when maltreatment of African wildlife is being discussed, calls to the spirits of other dead elephants as his tusks leave his homeland. With a corruptible Chinese embassy official (Pui Fan Lee), he performs a tango. Each person he has contact with gets smeared with white paste, or sometimes white dust, like a mark of shame. Somehow he manages to suggest the elephant’s tusks with just his outstretched arms.

The austere beauty of this production can’t be overstated. There are minimal props – a strip light for an office scene, boxes with lumps on for the ivory shop’s wares – but mostly it is a thing of shadows and silhouettes on two sets of gauze curtains, which are pulled across to change scenes by the four actors populating all the parts. Lighting changes shift the tone – blood red at the back of the stage when Mlima is dismembered, for example – and a small raised revolve on one side of the stage is regularly used to set him apart from the other actors.

Hanging portentously overhead is a huge lumpy object wrapped in grey plastic, suggestive of a consignment, but also doubling as the shape of an African elephant’s head when it’s behind a gauze. It is a constant reminder of things being bound up and shipped out, trade that isn’t just ivory but a whole continent of resources, a portion of it now owned by the Chinese.

There is a distinctive sound world here, too, gently noodling Afrobeat guitars as we wait for the start that switch to savannah sounds and then beautiful singing voices. One belongs to Brooks, who gives out a sound that’s part note, part howl in the scene where she and the other elephant spirits throng around Mlima, bewailing their fate. Spine-tingling.

The four actors are tirelessly effective, switching a hat or coat and reappearing as a totally new character, each with an immediate characteristic or verbal quirk. Brandon Grace moves with ease from the white Kenyan director of wildlife (pictured above with Siobhan) to the soignée Beijing shopper, while Pui Fan Lee is an indelibly authentic Vietnamese customs official, her cap set at a jaunty angle, as if to suggest his maverick tendencies, then a jazzily suited guest at the unveiling of what has become of Mlima. (Siobhan, Jones, and Brooks, pictured below)  In the final moments, Mlima returns centre stage, now covered in swirls of white paste to suggest the carving on his tusks, and moves into an extraordinary shoulder-rolling, whirling dance (the superb choreography throughout is by Shelley Maxwell). He addresses Mumbi, and the audience, with rising panic. His last word is “RUN!” Political theatre is definitely not dead, but not often this affectingly and effectively staged.

In the final moments, Mlima returns centre stage, now covered in swirls of white paste to suggest the carving on his tusks, and moves into an extraordinary shoulder-rolling, whirling dance (the superb choreography throughout is by Shelley Maxwell). He addresses Mumbi, and the audience, with rising panic. His last word is “RUN!” Political theatre is definitely not dead, but not often this affectingly and effectively staged.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

Add comment