Orson Welles: The Great Disruptor | reviews, news & interviews

Orson Welles: The Great Disruptor

Orson Welles: The Great Disruptor

A major BFI retrospective marks the centenary of the director's birth

No-one could joke about the tragic aspect of Orson Welles’s career, the fact that his inestimable promise had only been partially realised, better than Welles himself. Once, when asked about the outrage following his panic-inducing radio adaptation of War of the Worlds, the director quipped, “I didn’t go to jail. I went to Hollywood.” And that was punishment enough.

Welles, the boy wonder turned studio pariah, who nevertheless has more truly great films to his name than most filmmakers, was born 100 years ago: the BFI is marking the centenary with the retrospective Orson Welles: The Great Disruptor. One can see how tempting this title was for the season, for Welles certainly shook things up when he arrived in Hollywood in 1939 – with his personality, his ego, his ambition, his talent, all at a mere 25; even as an outcast wandering the world making films piecemeal, with next to no money, his very existence was a constant reminder of a way of making films, and of a determined artistic integrity that was anathema to the studio system that spurned him.

But “disruptor” only evokes part of Welles’s legacy; it also involves inspiration, innovation, magic and wonder. It’s not for nothing that Citizen Kane has spent its lifetime at or near the top of “greatest ever” lists; and it’s not for nothing that Richard Linklater has called Welles “the patron saint of indie filmmakers”.

The two-month season at the BFI Southbank, now underway for July and August, features a wide-ranging selection of Welles’s output, including the canonised classics – Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons, Chimes at Midnight; lesser seen titles such as The Trial, Journey into Fear, Mr Arkadin and The Immortal Story; and two films in which he appeared but did not direct, The Third Man and Jane Eyre.

The two-month season at the BFI Southbank, now underway for July and August, features a wide-ranging selection of Welles’s output, including the canonised classics – Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons, Chimes at Midnight; lesser seen titles such as The Trial, Journey into Fear, Mr Arkadin and The Immortal Story; and two films in which he appeared but did not direct, The Third Man and Jane Eyre.

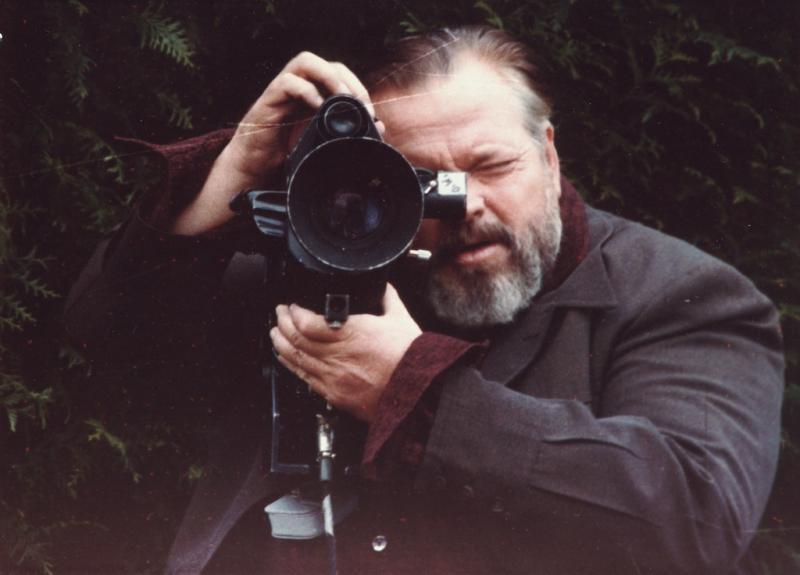

There are also some highlights of his work in television, notably Around the World With Orson Welles from 1955, a travelogue that Welles wrote, directed and hosted. And alongside a 1982 Arena programme about the great man is a new documentary, Magician: The Astonishing Life and Work of Orson Welles, which includes revealing and entertaining interviews with Welles, plucked from over half a century. Talks during the season include one by actor and Welles biographer Simon Callow, on the director’s Shakespeare adaptations.

One particular treat is the recently discovered Too Much Johnson, 40 minutes of film that Welles shot in 1938 – two years before Citizen Kane. Welles planned the film, which features his frequent collaborator Joseph Cotton (pictured above) as a philanderer pursued across New York by a cuckolded husband, as an element of a theatre play he was directing at the time. Prophetically, it was never used, and subsequently disappeared.

A few years ago we didn’t know that Too Much Johnson existed. The BFI retrospective and this film’s place in it reminds us that a career marked by unfinished projects, tied up in complications over materials and rights, seemingly lost, isn’t quite done with us. With Welles, we can still wonder what else lies around the corner.

As well as appearing in the BFI season, Magician: The Astonishing Life and Work of Orson Welles opens in selected cinemas UK-wide on 3 July, and Touch of Evil from 10 July.

Below, theartsdesk's film writers select some of their favourites from Welles’s career.

Citizen Kane (1941)

Citizen Kane (1941)

How does a film made in 1941 continue to retain such a hold on cinema folklore? One answer may be that few films have demonstrated the narrative possibility, technical invention, wit, imagination, bravura, mystery and romance of the medium – all of that, and more – so completely as Citizen Kane.

Welles and his co-writer Herman J Mankiewicz may have based their man on the yellow press baron William Randolph Hearst (and suffered for it), but their investigation of Kane’s life is so much more than biography – it’s a detective story and an existential mystery, an assembly of fractured memories and differing perspectives that creates what Borges called “a labyrinthine without a centre”. And to capture this on screen, Welles and cameraman Gregg Toland used a plethora of cinematic tricks – deep focus photography, expressionistic lighting, low-angle shots and complex interiors, montages and dissolves. None of these were new; the revolution was that Welles combined them all, the whole arsenal, as if nothing seemed more natural.

This rich mix results in one memorable scene after another, each rambunctiously acted by Welles and his Mercury Players from the theatre, the whole fuelled by Bernard Herrmann’s superb soundtrack. Welles rewrote the book on filmmaking so dazzlingly that Citizen Kane has rarely been emulated. When you watch the film, even today, everyone from Kurosawa to Tarantino falls into line. Demetrios Matheou

The Magnificent Ambersons (1942)

The Magnificent Ambersons (1942)

Orson Welles’s follow-up to Citizen Kane traces more fatalistically than Booth Tarkington’s elegiac source novel the decline of an upper-class Midwestern dynasty and its ritualistic enjoyment of sleigh rides, balls, cotillions, all-day picnics in the wood and serenades. Even the feebly upbeat ending shot by Robert Wise and the criminal slashing of 44 minutes in the director’s absence couldn’t deprive The Magnificent Ambersons of masterpiece status.

Welles built a mythic story of loss – as if expanding a world akin to that in Charles Foster Kane’s snow globe – from his intermittent voiceover narration, the montage-style editing, Bernard Herrmann’s music, Stanley Cortez’s lyrically ominous tracking shots in the Ambersons’ increasingly shadowy house, and the superlative performances of Joseph Cotten, Dolores Costello, Tim Holt, Anne Baxter, Agnes Moorehead (pictured above, with Cotten), Ray Collins, Richard Bennett and Everett Sloane. It’s a film about a young woman’s tragic spurning of her lover, her pampered son’s ruinous possessiveness, her unloved sister’s curdling, and it’s about the automobile befouling the pristine snowscapes and turning dear, old, turn-of-the-century Indianapolis into a city of ghosts. Graham Fuller

The Lady From Shanghai (1947)

The Lady From Shanghai (1947)

Despite his long fall from grace in the Forties, Welles continued to make incredible films. And there was clearly something in the air: a year after Hawks’s cryptic noir classic The Big Sleep, Welles made his own indecipherable but hypnotic noir, dubbed by one critic “the weirdest great movie ever made”.

Welles made the film purely for the money, but typically went about it with gusto and a determination to do things his own way. Shanghai was one of the first major Hollywood films to be shot almost entirely on location; he set out to shoot the entire film without close-ups, until Columbia boss Harry Cohn insisted. And he showed what he thought of studio image-making when, in the wake of Gilda, he had his femme fatale Rita Heyworth’s famous red locks shorn and dyed platinum blonde – Cohn was apoplectic, but the actress (pictured above, with Welles) was never more beautiful, or more effective.

Not surprisingly, Cohn put Welles’s edit through the wringer. But what survives is mesmerising, a humid, half-crazed waking dream whose stand-out scenes include the romantic tryst in the aquarium, the chase through San Francisco’s Chinatown, and the hall of mirrors sequence, all the more potent when we know that Welles and Heyworth were, in real life, estranged husband and wife. “The only way to stay out of trouble is to grow old,” sighs Welles’s hero at the end, “so I guess I’ll concentrate on that.” Demetrios Matheou

Touch of Evil (1958)

Touch of Evil (1958)

After a decade in Europe where he'd made a handful of interesting but less-than-classic films, Welles was keen to make a Hollywood comeback, though he initially signed on to Touch of Evil as an actor only. It was at the insistence of Charlton Heston, playing Mexican drug enforcement officer Mike Vargas, that Welles also got to direct. The source material wasn't promising – Welles adapted an existing Paul Monash screenplay without bothering to read the Whit Masterson novel it was based on – but from it he fashioned a thrilling vortex of expressionist, existential noir.

Welles is barely recognisable as the crippled and reekingly corrupt cop Hank Quinlan, a sweating gargoyle sunk in Stygian shadow. The setting, a Mexican border town called Los Robles, is a kind of surreal purgatory in a sinister no-man's land, peopled with a repertory company only Welles could have assembled – Marlene Dietrich, Akim Tamiroff, Zsa Zsa Gabor, an unbilled Joseph Cotten. The opening extended tracking shot has entered Hollywood mythology, as has Dietrich's enigmatic requiem for Quinlan, while many viewers may chiefly remember the provocative scene of Janet Leigh in her underwear. Naturally, Universal Pictures butchered Welles's edit, but nothing could stop Touch of Evil. As the screenwriter George Axelrod put it, "the film went from being a flop to a classic without passing through success." Adam Sweeting

Chimes at Midnight (1966)

Chimes at Midnight (1966)

“If I wanted to get into heaven on the basis of one movie, that's the one I would offer up,” Orson Welles said in a 1982 interview about Chimes at Midnight. He thought it his best film, as well as his favourite, and considered it his most personal, too: it’s certainly tempting to see Welles the rebel in Falstaff, but also the director's younger self, riling at his wastrel father, in Prince Hal.

Welles first approached Shakespeare’s history plays in the 1930s on the American stage, but he didn’t reach Chimes... until 1960, in Ireland, in his final stage production. When it came to the film, shooting in Spain in 1964-65 was typically improvisational; Welles even fibbed to his Spanish producer that he was making a more bankable film, an adaptation of Treasure Island. Sound quality suffered under such circumstances, but the black and cinematography is marvellous, and editing rarely more inventive than in the celebrated Battle of Shrewsbury scenes, which tapped anti-war sentiments of the time. The supporting cast – Keith Baxter as Hal, John Gielgud as Henry IV, Jeanne Moreau (pictured above, with Welles) and Margaret Rutherford – is first-class, but this is gloriously Welles’s film; his Falstaff is played for real tragedy, far more than the comedy we more frequently associate with the fat knight. Tom Birchenough

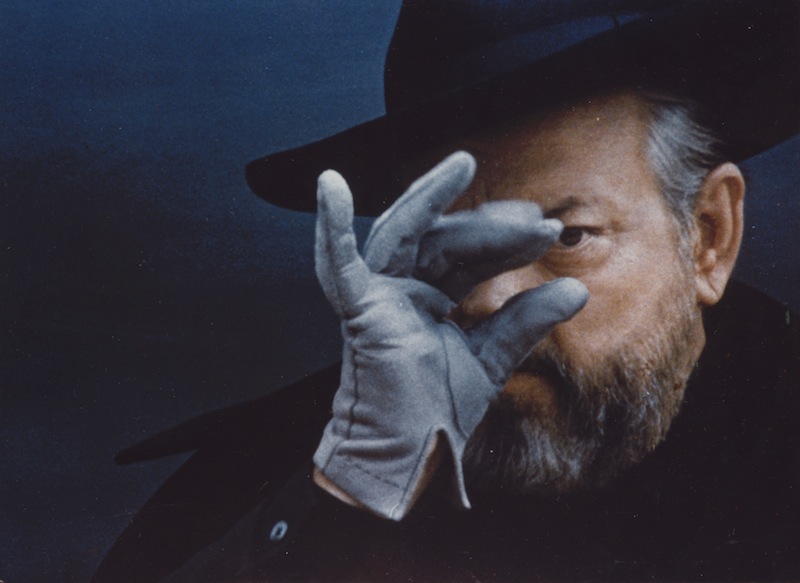

F For Fake (1975)

F For Fake (1975)

For his last film, Welles used his fondness for tall tales, misdirection and sleight of hand to dazzlingly compensate for the usual lack of funds. With someone else’s documentary footage about master art forger Elmyr De Hory as raw material, and his young girlfriend Oja Kodar as his provocative star, Welles conjured a playful yarn about art’s unreliability. The director pops up in the editing room, in Ibiza, and holding forth – puffing cigars and eating hungrily – in a favourite Paris haunt. Howard Hughes and Picasso find themselves in Orson’s web, often spun from thin air. Bookending a career that began with Citizen Kane, F for Fake is a brilliant confidence trick; and brilliance, confidence and trickery were Welles’s qualities which rarely ran dry. Nick Hasted

Overleaf: watch the trailer for Magician: The Astonishing Life and Work of Orson Welles

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

Add comment