Democracy, Old Vic | reviews, news & interviews

Democracy, Old Vic

Democracy, Old Vic

A welcome revival of Michael Frayn's complex portrait of political compromise and personal treason

You might not think that a drama about German parliamentary politics in the 1970s would be of great urgency today. But when Democracy, Michael Frayn's play about Willy Brandt and the Günter Guillaume spy scandal, first opened in 2003, Brits swiftly discerned links with another charismatic politician, the first left-wing leader in decades, while across the Atlantic the womanising German Chancellor looked very much like Bill Clinton.

Brandt ended his first speech after being elected Chancellor in 1969 with the famous promise, quoted repeatedly in the play, that he intended to "dare more democracy". He would receive the Nobel Peace Prize for his Ostpolitik, which took one of the first steps towards ending the Cold War.

There's an awful lot of ground to cover in a narrative spanning five momentous years

With his irreproachable wartime record and instinct for the common touch he was immensely popular. Rainer Werner Fassbinder ended The Marriage of Maria Braun, his 1979 film about the deep compromises running through post-war Germany, with a series of portraits of Chancellors which suggested a direct lineage from Hitler to Helmut Schmidt. One face was missing from the rogues' gallery: Willy Brandt's.

But Brandt was also a flawed hero: indecisive, depressive and prone to heavy drinking and womanising. Guillaume, his close personal aide who turned out to be a Stasi spy, was to be his downfall. It's this episode which occupies Frayn's multi-layered play, revived at the Crucible Sheffield earlier this year and now transferring to the Old Vic.

In a 2003 interview the writer reflected that Brits were chiefly interested in the Nazi era of German history. Since then things have changed somewhat and films such as Goodbye Lenin, The Baader Meinhof Complex and, especially, the Oscar-winning The Lives of Others have piqued people's curiosity about Cold War Germany on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

So today's audiences may bring a greater level of expectation to the show. All the same, there's an awful lot of ground to cover in a narrative spanning five momentous years. Dense with political exposition and short explanatory scenes, the opening scenes have the scent of a John Le Carré thriller. But this production, by Paul Miller, at times feels like heavy going, with much static declamation and high-level smoking by serious grey-haired men standing around in grey suits. And, set within Germany's very different political Gestalt, the coalition theme (Brandt's party had formed a precarious alliance with the Liberal Democrats) sounds only very vague topical echoes.

But Democracy is in part a comedy and the joker in the pack is Guillaume, "Berlin meatball", as Brandt describes him and cheery general factotum ("No job too big or too small"). With his glasses, moustache and bushy hair, he resembles a Germanic Groucho Marx; all that's missing is the cigar. Rummaging in filing cabinets, playing catch with top-secret dossiers, he scoots and loops indefatigably around the corridors of power in his ill-fitting suit. While he comments on proceedings in asides either directly to the audience or to his Stasi spymaster, Guillaume, in Aidan McArdle's virtuoso performance, seems to emerge early on as the play's main character.

But Democracy is in part a comedy and the joker in the pack is Guillaume, "Berlin meatball", as Brandt describes him and cheery general factotum ("No job too big or too small"). With his glasses, moustache and bushy hair, he resembles a Germanic Groucho Marx; all that's missing is the cigar. Rummaging in filing cabinets, playing catch with top-secret dossiers, he scoots and loops indefatigably around the corridors of power in his ill-fitting suit. While he comments on proceedings in asides either directly to the audience or to his Stasi spymaster, Guillaume, in Aidan McArdle's virtuoso performance, seems to emerge early on as the play's main character.

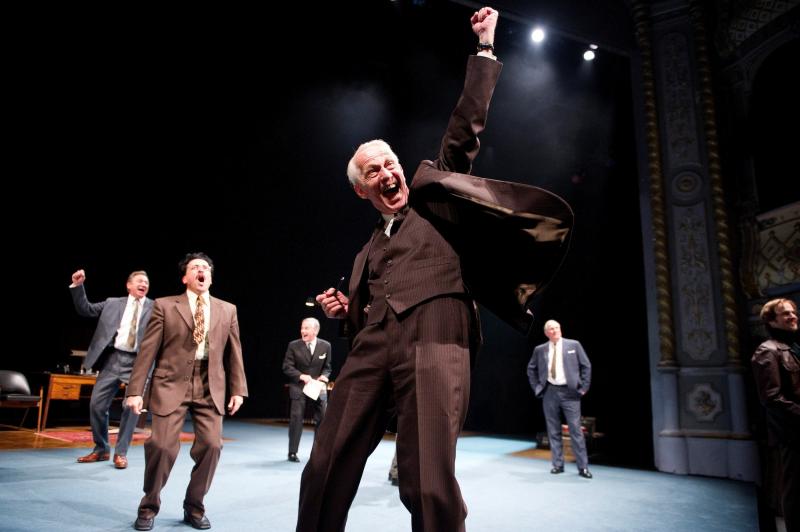

By contrast Patrick Drury (pictured above with McArdle) doesn't nail either Brandt's big physical presence or personal charm and the production feels rather decentred until the two men's first big scene together a good half hour in. And their relationship really comes into focus in the second half, which begins with a joint family holiday in Norway with Brandt, his Norwegian wife and son, plus the trusted aide with his own wife and son.

Just as the families mirror each other so, it turns out, do the two men, each scarred by the sense of having been let down by an absent father (Brandt was illegitimate and never met his; Guillaume's was a Nazi who committed suicide after the war). In a key conversation freighted with resonance and ambiguity, they acknowledge their similarities and Brandt speaks of his own spying activities during the war, even as he now strongly suspects his confidant is spying on him.

Democracy, by the way, has no female characters - other than a brief voice-off - though the presence of women is everywhere palpable. But it's certainly not a two-hander. Among the sharply-etched, gossiping and back-stabbing mandarins around Brandt are David Mallinson as a dyspectic and envious Helmut Schmidt, Chancellor-in-waiting, William Hoyland as the avuncular, pipe-smoking, devious Herbert Wehner and Richard Hope as a bungling head of security.

rating

Buy

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

The Producers, Garrick Theatre review - Ve haf vays of making you laugh

You probably know what's coming, but it's such great fun!

The Producers, Garrick Theatre review - Ve haf vays of making you laugh

You probably know what's coming, but it's such great fun!

Not Your Superwoman, Bush Theatre review - powerful tribute to the plight and perseverance of Black women

Golda Rosheuvel and Letitia Wright excel in a super new play

Not Your Superwoman, Bush Theatre review - powerful tribute to the plight and perseverance of Black women

Golda Rosheuvel and Letitia Wright excel in a super new play

Cow | Deer, Royal Court review - paradox-rich account of non-human life

Experimental work about nature led by Katie Mitchell is both extraordinary and banal

Cow | Deer, Royal Court review - paradox-rich account of non-human life

Experimental work about nature led by Katie Mitchell is both extraordinary and banal

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

Born with Teeth, Wyndham's Theatre review - electric sparring match between Shakespeare and Marlowe

Rival Elizabethan playwrights in an up-to-the-minute encounter

Born with Teeth, Wyndham's Theatre review - electric sparring match between Shakespeare and Marlowe

Rival Elizabethan playwrights in an up-to-the-minute encounter

Add comment