Athol Fugard - Falls the Shadow, Sky Arts 1 | reviews, news & interviews

Athol Fugard - Falls the Shadow, Sky Arts 1

Athol Fugard - Falls the Shadow, Sky Arts 1

Documentary on South African playwright is involving, informative - and incomplete

Athol Fugard's 80th birthday is being marked by four major productions in New York this year, two of which have come and gone. How has the London stage honoured this 11 June milestone in the life of the South African playwright for whom the personal and the political have become inextricably linked across the years?

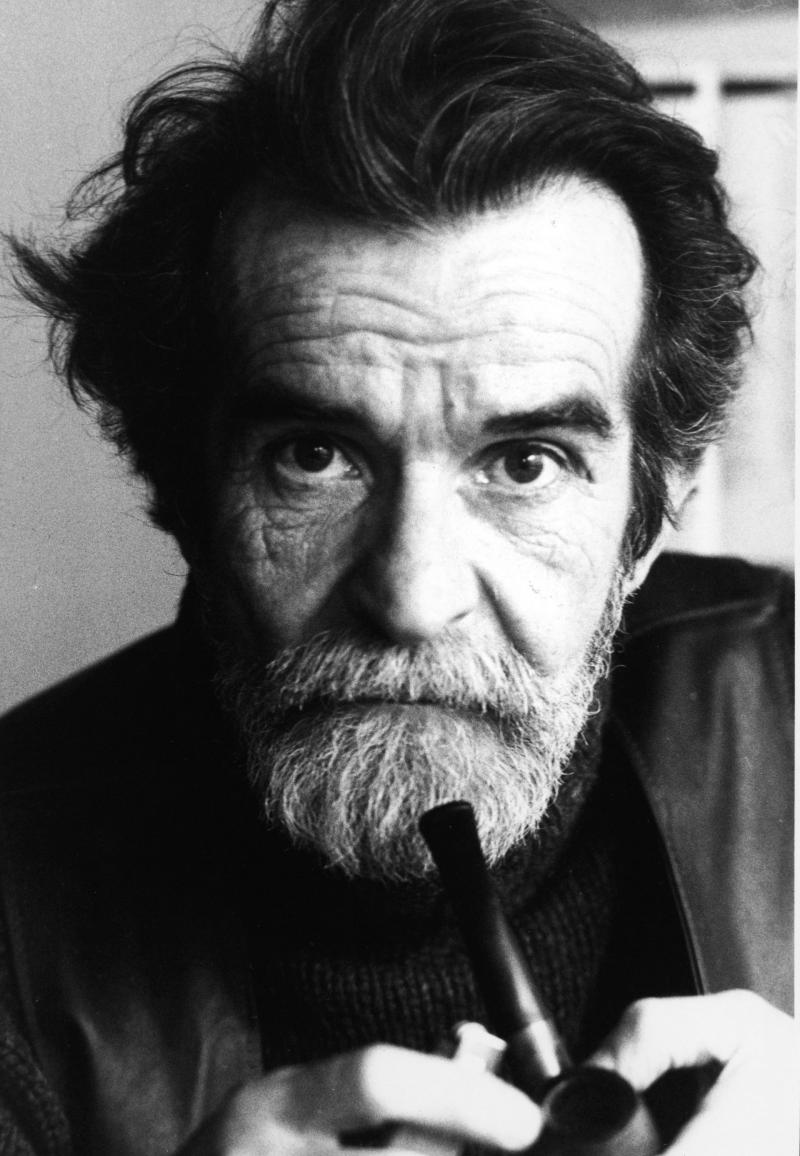

That might seem a strange charge to level at a documentary running more than two and a quarter hours that folds Britain, America and, of course, South Africa into its humane and capacious embrace. But for all that Falls the Shadow illuminates an unwavering and merciless political critic whose dramas reveal a surpassing empathy as well, Palmer's decade-spanning narrative says too little about the Fugard of late, not to mention this writer in the here and now. This lapse is especially marked given that much of the contemporary footage of Fugard in all his lined and wizened splendour was shot at the Signature Theatre, the invaluable Off Broadway company that right now is midway through a three-play sequence of his work. (And one visual gaffe: a mock-up marquee of one of his plays renders the great Ruby Dee as Ruby Lee.)

You want to know the origins of such seminal Fugard texts as Blood Knot, Sizwe Bansi is Dead, The Road to Mecca, and "Master Harold" ... and the Boys, the last of which received its incandescent world premiere at the Yale Repertory Theatre during my student days in Connecticut? (Indeed, Fugard received an honorary doctorate from Yale in 1983, as, for what it's worth, did Meryl Streep.) You get all that and more besides, the celluloid footage from Mecca especially illuminating given that the screen version, co-starring Fugard, Kathy Bates, and the late Yvonne Bryceland, is all but impossible to locate (pictured above: Rosemary Harris and Carla Gugino in the recent Broadway revival of the same play: photo, Joan Marcus).

You want to know the origins of such seminal Fugard texts as Blood Knot, Sizwe Bansi is Dead, The Road to Mecca, and "Master Harold" ... and the Boys, the last of which received its incandescent world premiere at the Yale Repertory Theatre during my student days in Connecticut? (Indeed, Fugard received an honorary doctorate from Yale in 1983, as, for what it's worth, did Meryl Streep.) You get all that and more besides, the celluloid footage from Mecca especially illuminating given that the screen version, co-starring Fugard, Kathy Bates, and the late Yvonne Bryceland, is all but impossible to locate (pictured above: Rosemary Harris and Carla Gugino in the recent Broadway revival of the same play: photo, Joan Marcus).

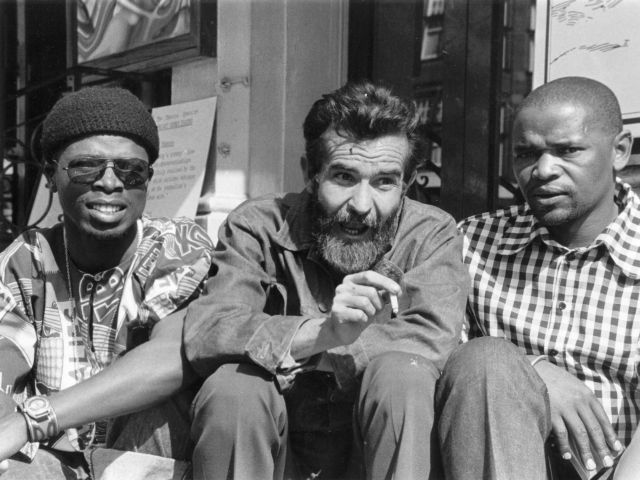

What you won't find is much analysis of the shifting sands of Fugard's work post-apartheid, as an authorial conscience once defined by the enemy has had to adjust its horizons accordingly, the results on often rending if less globally acclaimed view in plays like The Train Driver, My Children! My Africa!, and Valley Song: none of those titles is afforded more than a cursory glimpse, if that. The film's more pressing concerns have to do with the landscape that shaped Fugard's defiant poetics, literally so in the imposing severity of the Karoo desert, and politically via an abhorrent government-backed policy that meant, for instance, that John Kani and Winston Ntshona could share Broadway's 1975 Tony Award for Best Actor for two Fugard plays even as they had absolutely no standing as people, let alone artists, back home; upon their return to South Africa, both men were promptly arrested (pictured below: Kani and Ntshona frame a youthful Fugard).

Archival footage mixes highlights from various Tony ceremonies (Fugard's Lifetime Achievement Award last year included) with shocking reminders of his homeland's toxic past. It's more than a little jolting in 2012 to come across the country's one-time prime minister, Hendrik Verwoerd, and his assessment of apartheid as "a policy of good neighbourliness", or to see a white South African from that era speak of his black countrymen as "only just come down from the trees". The Sharpeville massacre in 1960 and subsequent desecration of Cape Town's District Six resound poignantly today, the latter now home all these decades on to the city's Fugard Theatre, which opened its doors early in 2010. (The playhouse was commissioned by Eric Abraham, the South Africa-born impresario who also co-produced Palmer's film.)

Archival footage mixes highlights from various Tony ceremonies (Fugard's Lifetime Achievement Award last year included) with shocking reminders of his homeland's toxic past. It's more than a little jolting in 2012 to come across the country's one-time prime minister, Hendrik Verwoerd, and his assessment of apartheid as "a policy of good neighbourliness", or to see a white South African from that era speak of his black countrymen as "only just come down from the trees". The Sharpeville massacre in 1960 and subsequent desecration of Cape Town's District Six resound poignantly today, the latter now home all these decades on to the city's Fugard Theatre, which opened its doors early in 2010. (The playhouse was commissioned by Eric Abraham, the South Africa-born impresario who also co-produced Palmer's film.)

Abraham joins Kani, Ntshona, Janet Suzman and James Earl Jones among the eloquent interviewees who explain how it is that Fugard has become the most performed playwright in the world after Shakespeare, a statistic put forth at the programme's opening that I admit was news to me. (A shame that Danny Glover, for one, didn't partake, given his profound association with Fugard over time.) But Palmer finishes, as he must, with an aggrieved close-up on the man himself, who is heard expressing sorrow at the limitations of the artist and at his feelings of betrayal by the far-from-utopian South Africa that now exists. Fugard's despair, in turn, must be set against the bequest of a show that encourages our thanks for the wisdom and the work, neither of which shows signs of abating any time soon. With that in mind, can we have a sequel?

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

Alien: Earth, Disney+ review - was this interstellar journey really necessary?

Noah Hawley's lavish sci-fi series brings Ridley Scott's monster back home

Alien: Earth, Disney+ review - was this interstellar journey really necessary?

Noah Hawley's lavish sci-fi series brings Ridley Scott's monster back home

Add comment