theartsdesk Q&A: Composer James Dillon | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Composer James Dillon

theartsdesk Q&A: Composer James Dillon

As Glasgow awaits his epic new work, the controversial Scot sets the world to rights

Glaswegian James Dillon (b 1950) is one Britain's most critically acclaimed living composers. Early detours as a drunken and drug-taking wastrel gave way to what he calls "musical terrorism". By which he means his blistering career as one of the most intoxicating and uncompromising of the New Complexity school of composers.

Last year we met and chewed the musical fat on the Eurostar, returning to London from another one of Dillon's foreign premieres, The Leuven Triptych. (He claims more than 70 per cent of his works are premiered abroad.) He spoke to me about the conservative hand of the British musical mafia, the neglect of his music by reactionary British institutions, the dangers of Minimalism (and acid and consumerism), the Nazism of the rock concert and conducting Russian pigs. I felt like I was with Lenin and we were about to storm St Petersburg - or at least the Royal Festival Hall.

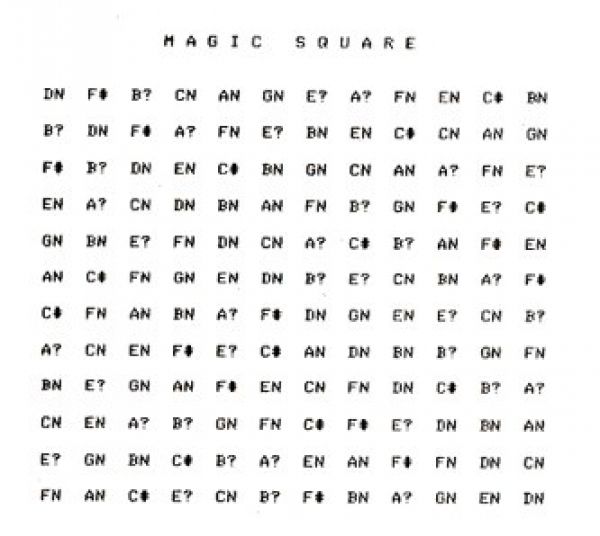

IGOR TORONYI-LALIC: I was talking to Sir Peter Maxwell Davies recently and we discussed his use of magic squares [a numerical way of generating and ordering music that was used by 12-tone composers; a sample square is pictured right]...

JAMES DILLON: Oh God.

[Laughs.]

Do you use any system like that?

No. I use much more complex systems than magic squares. I'm fascinated by certain things like chaos theory. God, magic squares. They're so cute those things. [Laughter.] There's no doubt that you can build up a certain complexity with these things. It all depends on how you're applying them. When I first started studying music seriously, magic squares were everywhere. And I vowed I'd never touch them. I hate anything that becomes fashionable. Maxwell Davies anchored himself to these damned things for like 30 or 40 years or whatever. And the results half the time seem dreadful to me.

For some people, the music that is built on magic squares or, as you mention, in your case, chaos theory, provides too much rupture too early.

Hm. Do you think that matters?

Well it doesn't matter to me because I've put in the work. But I imagine most people would respond more to process music - Spectralism or Minimalism - which starts somewhere familiar and then ruptures that familiarity.

I would like to test your theory. I've had good experiences... You're alluding to a debate that is going on about new music. Is it accessible blah blah blah? I think most of that debate is complete bullshit. First of all, rarely does an uneducated audience ever get exposed to this music. They're spoon-fed crap from this age... Music is the strangest of the arts in the sense that most people feel that they know what music is even though they have no musical training. But they wouldn't say the same thing about painting and writing. Partly that's to do with the fact that music is around us. It's ambient and it's everywhere. It's in shops. It's in lifts. It's coming out of the radio constantly. It's background sound in TV programmes. And most of what they hear most of the time is a very narrow band-width of the music that exists. It ranges from light pop to quasi-heavy pop. There are certain kinds of music that play a very dangerous game. They verge on pop music. Minimalism is an obvious example, Philip Glass etc.

There are a lot of crap performances of modern music: mediocre, under-rehearsed, half-digested, that should never be put before the public

How is that dangerous?

Dangerous in that it reinforces this consumerist linkage with the music. In other words, in the end, there is a kind of discourse built around this music which suggests that it is somehow more popular because it approximates to a consumerist culture, ie pop music. I don't know how one tests this. Because even popular music is not popular. One of the most interesting statistics I saw about 15 years ago - you're too young - it was declared that the Spice Girls were the biggest pop group in the world. But I read this article on the plane, and it was saying that the Spice Girls don't make any money from CD sales; they make money from merchandising themselves. You know: TV, controlling their photos. It was about all of the paraphernalia around them. So one has to question what popular is. When some of these bands go on the road, the sheer cost of the spectacle going on, the sums don't add up. When you put these spectacles on in stadiums with 25,000 people, people are there because they get wrapped up in that hysteria, in the publicity and propaganda.

We live in this subcultural world in contemporary music. I don't necessarily think this is such a bad thing. I don't know if you've ever been to Strasbourg. Two years ago they played my piano concerto there. Strasbourg is one of the best festivals in Europe. It was played to 3,500 people who paid through the door. The audiences are there when people perform me at the Proms. I know they're not there for me exclusively but... It's difficult. Contemporary music has a constituency that is very spread out globally. I think people still think in old-fashioned ways: bums on seats through a particular theatre. But even if one looks at the South Bank, they can't generate audiences and they try every gimmick under the sun. The whole notion of popular music is dangerous in the sense that it generates a kind of artificial comparison, an artificial discourse.

So do you believe that someone who was educated in Modernist music from the day they were born would accept it?

One can't generalise like this. You can't fool anybody, educated or uneducated, with inauthentic performances. There are a lot of crap performances of modern music: mediocre, under-rehearsed, half-digested, that should never be put before the public. I'm sure if you put people into that audience last night, even those who knew nothing about the music would have been won over by the energy of it. They might not have understood the language but that doesn't matter because sometimes that's how we respond to the music. We respond on so many levels. I genuinely believe that the discourse around the categorisation of music and its accessibility is simplistic. Way, way too simplistic. What we need is less performances but more high-quality performances. And that's right across the board in all music.

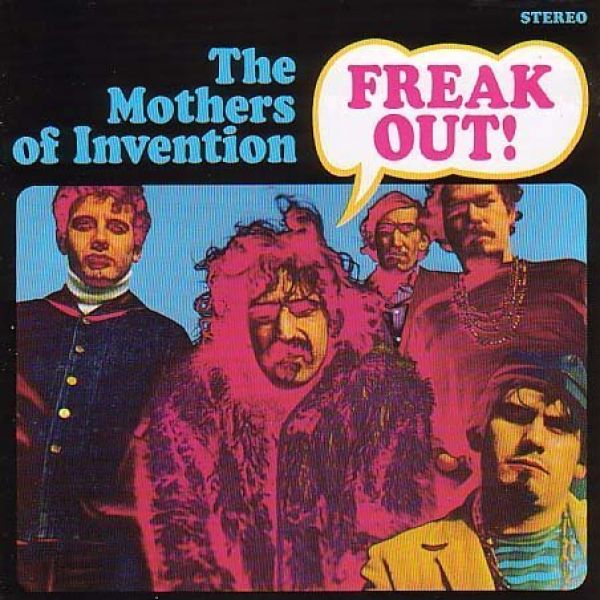

I discovered Varèse from the back of Freak Out! by Frank Zappa. I thought he was a blues singer or something

So how does one become a composer? What was your first exposure to classical music?

That was at school like most people. I had Rachmaninov rammed down my throat. I eventually learnt to love Rachmaninov but while I was at school I hated it.

Same. I came back to him through the Fourth Piano Concerto.

For me it was the Second Symphony. I grew up at the time when rock music was at its peak. You talk about Maxwell Davies but for me the best British music at that time was The Beatles, The Kinks, The Stones, The Small Faces, The Who etc. I was part of that as a teenager at school. But when I was 19 I discovered Webern and Stravinsky. I became fascinated by Webern's Five Bagatelles. I couldn't work it out. I hadn't heard anything like it. It seemed either that there was something lacking in my education or that this guy was kind of, like, nuts. I investigated it. I discovered that there was a Second Viennese School. From Stravinsky I discovered Varèse. That's not quite true actually. I discovered Varèse from the back of Freak Out! by Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention (pictured left). It mentions Varèse and I was kind of curious because I thought he was a blues singer or something.

I had been living in Cornwall, hanging out on the beach and doing gigs in pubs, taking a lot of drugs, and acting kind of like I was going to kill myself

You were in a band at that time. What did your fellow band members think of you and your investigations? Were they exploring the same things?

I was betwixt and between at that point when I discovered Webern. There was a lot of change of personnel in the band. I couldn't quite place some of the ideas I was having. I hated progressive rock for example, ie Yes and Genesis and all that kind of stuff. I thought it was so very phony.

Sort of Spectral music in some ways?

Hm. Yes, no. All music is Spectral really, it's just some people like to call it Spectralism because they like the label that's stuck to them because they then have an identity. "Separate me from the rest of the crowd!" It's bullshit. There are only four Spectral composers anyway (Gérard Grisey, one of the founding fathers of Spectralism, pictured right), all the others are just fakes.

So...

So I started. How do I put it? I cut myself off from that world completely. I moved to London. I had been living in Cornwall, hanging out on the beach and playing, doing gigs in pubs, taking a lot of drugs, and acting kind of like I was going to kill myself. I got quite ill.

How did you find yourself on that path?

Well I didn't go to music school. When I was 19 or 20 I knew that I was not cut out to go to university. I'd already done a year at art school and I never turned up. Most of the time I was drunk. I moved away from home. I was hanging out in folk clubs in Glasgow and a lot of drinking went on. And I could never handle drink. Which meant I was always drunk [laughs]. I cut myself off completely. I moved to London. I didn't know anyone in London at all. I met a girl and we moved in together and she straightened me out.

Was she a musician?

No, she was a computer scientist.

That might have been useful?

It wasn't [laughter]. Theoretically it should have been but we couldn't talk about things like that. We'd always end up arguing because I always thought I knew more than I did.

So then you went down to Cornwall. Was it a hippy commune?

Kind of. I wouldn't call it a hippy commune because we hated hippies at the time, even though everyone else called us hippies. I was moving around people's places. Staying in different places. It was a very, very acidy scene. One of the biggest pushers was Lord Eliot. He runs Port Eliot. He used to hang around Cornwall in a Gypsy caravan, selling acid. It was a way, way-out scene. But if you are a small build like me your constitution packs in after one... [descends into laughter]. Mind you, all the big guys died of heroin. I escaped all of this.

None of the drug-taking helped you to, as the cliché would have it, open your mind?

You can't romanticise it. I don't know if you've ever taken acid but if you take an acid trip, the minute you start getting high, you also start getting worried. When are you ever going to come down? So you spend about 50 per cent of the time enjoying it, and about 50 per cent of the time thinking, shit, not me, I don't want to end up as one of those acid heads with holes in my brain! So I don't know about mind expansion. We do that all the time anyway. We daydream. So I don't know. I don't have any romantic attachment to that notion. Timothy Leary was an utter idiot but he had interesting ideas. So what do you do? How do you discuss that rationally?

And you started to teach yourself composition?

I didn't go to school. I settled down in London. I had the problem of how do I earn a living. I began to take private lessons with people, with Punita Gupta on Indian music. I went to see her initially to understand Indian rhythm. I thought I understood it but I didn't. And she insisted I play tabla. I spent a year with her. Although she was a sitarist not a tabla player but she knew all the talas [the Indian rhythms] so she would sing them to me and I had to repeat them back to her.

When was this?

1972, must be.

And by then did you know you wanted to compose?

1971, I was really lucky to catch Boulez's Roundhouse concerts. I steeped myself in that stuff. I heard some very fine performances of Kagel, Stockhausen, Varèse. So I was bidden.

I'm not very keen on hypnotics, which is why I gave up acid

A lot of people start by mastering conventional harmony. Did you do that legwork?

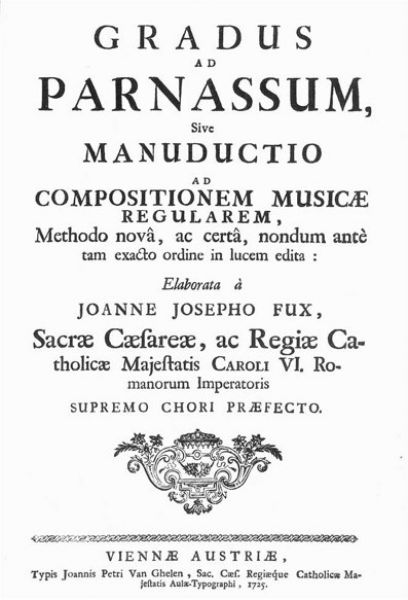

I don't know if I mastered it. I suddenly found myself endlessly at home. I did Fux's Gradus ad Parnassum (pictured left). It was a discipline for me. I had this nagging thing that I have to learn this. I can't neglect it, because some day I'm going to be confronted by it.

And did you also study Rimsky-Korsakov and Schoenberg etc?

Rimsky's Principles of Orchestration? Not really.

Was that not useful?

It is probably useful to some extent but instrumentation is a very strange thing. And I've discovered this through teaching it myself. Orchestration class is one of the classes I teach now [at the University of Minnesota, where Dillon is the Professor of Composition]. The kind of thing you can't teach is a feeling for instruments. Reading about them is not interesting in itself. You really just have to learn what these things sound like and what they might be capable of, where their boundaries are as instruments. And that just comes through familiarity as much as anything else. Some people have a feeling for instruments and some don't. Some see musical material almost divorced from instruments and the sounds they make. Other composers are interested in the internal architecture of the instruments itself as much as the so called abstract musical material.

Listen to the Royal National Scottish Orchestra perform Dillon's La Navette at this year's Proms:

Did you bring in anything from your pop and rock background?

I was fascinated by the act of performance as a visual spectacle in itself. Not in the sense of the camp, heavy-metal spectacle, wiggling your bum in the air and all that. In the sense of the intensity of a situation. I've felt a lot of contemporary performances have lacked a certain real tension in the air. When it happens it's amazing, particularly with acoustic instruments, with the aid of volume.

Composers who start out in rock and pop are usually drawn to Minimalism. Why was there no fascination in Minimalism for you?

I'm not very keen on hypnotics, which is why I gave up acid. They render you mindless in the end. There's something essentially both ideologically and politically dangerous about it. They involve a lack of internal critic, expressed partly in the lack of rupture. Though, I love very early Terry Riley. The stuff from the mid-1960s: In C, the keyboard studies, those things are amazing. Or his own albums, things like Persian Surgery Dervishes (below). Stuff he made himself on a little cheap analogue organ. He sat on the floor and just improvised. But he would layer it. I like that. The thing I did like about that early stuff was the phase structures. I was interested in phase. That also came from the fact that I played electric guitar. And I was interested in phase in terms of electrical processes.

Listen to an excerpt from Terry Riley's Persian Surgery Dervishes (1970):

You also got into Dowland. How?

I switched from guitar to lute. It was a discipline thing. I wanted to calm my ears down after all this electrical amplification. I wanted more and finer control of my fingers. Renaissance church music was easy for me because up to the age of 13 I was an altar boy in the Catholic church. So all the Catholic church music was in my head. It was a strange memory. I walked away from the Catholic Church but I still have an attraction to it, its ritual and its musical corps.

What did your parents think of your journey into this recherche classical world?

My father's dead. My mum found herself educating herself. She become fascinated.

Were they musicians?

I come from a family of jazz musicians. I have an uncle who had a band called the Chicagonians in Glasgow. Annie Ross is my mother's cousin. She sang with Dizzie Gillespie. There used to be a trio called Lambert, Hendricks, Ross, a skat trio, famous for technical dexterity.

Listen to Lambert, Hendricks, Ross's 1959 song "Cloudburst":

And your mum would come to contemporary concerts and enjoy them?

Well, she comes to mine [laughs]. I don't know if she goes to anyone else's. I don't think so but... Most of my family are from Scotland and that's why I defy to accept this notion of what's accessible or not. For them it's as strange a world as listening to Mongolian music or the music of the bushmen of Kalahari. But they sense when something's authentic. They sense when there's an authenticity about the performance itself. There's an intensity. There's an engagement. Even if they don't understand the language, they like the noise it makes, to quote Thomas Beecham.

I didn't come from that world of privilege, of knowing every grant available, of having your family know everybody on every jury. That's why I decided to study on my own

Dillug-Kefitsah (1976) for solo piano was your first official composition. What a great opening to your compositional career. Was it a distillation of years of work?

A lot of early work was withdrawn. I started too ambitiously. I started writing very big pieces and I didn't really have the technique to do it. With Dillug-Kefitsah I wanted to strip everything away and start again.

What does Dillug-Kefitsah mean?

It's Hebrew for hopping and skipping. It comes from a text, The Book of Splendours, by a medieval Jewish Kabbalist based in Spain called Abulafia. He wrote this book and he talks about the Dillug-Kefitsah. It's basically the same thing as Freudian free association. Freud didn't come from nowhere; he came out of a long Jewish tradition of dream interpretation. In the medieval period it was very common for Jewish dream interpreters to move from village to village and they would make a living out of telling you what your dreams were about. So hopping and skipping was a term he applied to a notion for a mental process of creation. He tries to systematise it and, like a lot of Kabbalists, he gives you instructions.

And then you were invited to Darmstadt [the mecca for contemporary classical music] in 1982. Your star rose very quickly. You became associated with the New Complexity group. A label that you don't like.

Well, I gave an interview in 1984 with Richard Toop. And he wrote this article called Four Facets of New Complexity. And I kind of regret it. Because if you read between the lines of my interview, you can already see I'm resisting a lot of what he's putting to me. And I refused for example to participate in giving him an analysis of my other pieces. I told him, "You're a theorist, analyse it yourself." So there was already tension there. But since then there's been this broad brushstroke. And it means that, particularly in Britain, which has struggled to really embrace Modernism, there's a big target. One can write them off as one group. A group that must almost be involved in some sort of sect. "They must be no good because they want to bring the whole "cowpat" tradition to its knees!"

Listen to Dillon's Second String Quartet performed by the Arditti Quartet:

But by then there was no need to be reacting against the "cowpat" tradition was there? By the 1980s that was long gone?

Well, mentally I don't know if it was. People were writing in different styles.

In interviews at the time you say that you were reacting against things that you were angry about in certain ways. Which things?

Well, the dominant school in Britain at the moment was the Manchester School.

So you were even rejecting the British Modernists?

I wasn't attracted to them sonically. I didn't like their sound.

Not even Birtwistle?

No, absolutey. I have an admiration for him because of his resilient refusal to make nice music, shall we say, but I find it very dissonant. Dissonant not in the reactionary sense of the word. I mean in the sense that it has material that deliberately or not lies alongside each other in a way that I find aurally uninteresting. It's dissonant in that sense. I was never concerned about that.

When I was 20 I really wanted to study with Messiaen. I discovered Messiaen about a year after Stravinsky. And I didn't know how you did that. I didn't come from that world of privilege, of knowing every grant available, of having your family know everybody on every jury. Politically it was anathema to me. And I didn't know how you did it. That's why I decided to study on my own. I was forced to. In retrospect I'm glad. Because it gave me independence. The system is very little to do with teaching; it's to do with networking. And I despise that whole world.

It's a dangerous thing to say. You say that in Britain and people will spend five years taking revenge. You know one small slippage of the language and they'll screw you

Do you acknowledge some of the points that Toop made about your music in that essay: the dense notation, for example or...

I can't deny that. Complexity for me lies in other places. It's something to do with the depth of thinking behind something. Complexity is going to have an uncontrollable element. There's going to be a certain noise in any kind of complex system. It's one of the defining features of a complex system. It's non-linear. Noise is non-linear. If you take that to another level, there is also not a one-to-one correlation between the way you think and the music that you produce. Because that's also non-linear. One goes through a labyrinthine process to create it. Which is why I suppose I was trying to force Toop to analyse something because I wanted him to reveal what he thought about the process, beyond, "Oh my god, black pages!" (A score by New Complexity composer Brian Ferneyhough picture above right.)

But were you deliberately trying to make things difficult for performers? Because that's what people like Toop are suggesting.

No. And even Ferneyhough probably regretted ever suggesting that somehow this music is engaged with the struggle and energy because it is continuously thrown back at him. I was looking for an endless intensity that means that you rarefy the musical space so much that it does involve a certain complexity of learning. And there's a heavy price to pay for that. One of the things that New Complexity isn't given credit for is that they were willing to pay that price. You're not going to get as many performances. For example, there's a very famous composer-conductor, same generation as me - you work it out - who, every time I bumped into him in Kilburn High Road, would go, like a mantra, "Oh James, when are you going to write something that we can do in two rehearsals?" Why would I want to? I'm not desperate for performances. I'm engaged with the project. It means that you make sacrifices. Anyway, I've always been sustained by being outside Britain. The BBC is the only place that has been consistent with me musically. All the other established institutions in Britain have not been interested.

Do you think that's because of the label?

It's a combination of the label and I don't know if my personality helps. I probably come across as intolerant - I'm not sure if that's the right word because I don't think I'm intolerant. I can feel forces trying to put me in a space I don't want to be. So I'll dismiss it. It can cause me certain problems. This has usually been done by non-musical people who have agendas.

Many people will be surprised that you don't like Birtwistle and Maxwell Davies?

No, no, I didn't say I don't like it. I just wasn't interested. That's already a dangerous thing to say. You say that in Britain and people will spend five years taking revenge on it. I'm serious. That's how it is. One small slippage of the language and they'll screw you.

But my point is that they're Modernists. And if New Complexity was about anything it was about reinvestigating the Modernism of total serialism, wasn't it? So it's odd you weren't interested in them.

Some people looked at it that way. It certainly wasn't that for me. I don't even think it was that for people like Chris Dench (pictured left). I knew him before all this broke in the early 1980s. He was interested in too many things for it to be just about integral serialism. I've always been fascinated by certain aspects of the sciences and also the other arts. And Dench is similar in that way. And so what you end up with is something that approximates to being alive today. We are being bombarded with everything; we have access to everything. [One philosopher] talked about reducing the world to these endless lists and irrefutable tables. That's the world we have. So what do we make of that? Does it all become relativism? Do you still believe in some meaning in all this somewhere. The meaning comes down in the end to some small nuanced human contact. Whether it's the contact of the finger on a fingerboard making a small adjustment of sound or whether it's a human gaze. There's still meaning there.

What people might not understand is how you make your musical judgements at the early stages of composition when you're putting ideas through the number crunchers...

That was only for last night. I was playing around with typical Renaissance games in the way that Guillaume Dufay would have.

But a Romantic composer would find a tune and decide whether it's pretty or not. What is the equivalent process for you?

I am also looking for a tune. But my definition of a tune is not the same as Richard Strauss's. Regardless of how much I like his tunes.

What is that definition, and how do you expect the audience to understand what that definition to be?

It's more about in-tune-ness. If you know what I mean.

The world is not England for me. It's not dictated by England for me. It never has been

Can you explain that?

It's tied up with this thing that I was talking about. You can't fool an audience with a bad performance. When an audience becomes genuinely engaged - and you can feel it in the room - an audience that's really concentrating and that you have under your spell, an enchantment goes on. It's a very mysterious process how one moves an audience in that way. And I don't know if you can really explain it.

So to drag it down to the simplest level, you will be faced with sequences of notes. How do you decide which one to use and which one to discard?

Do you know Robert Graves's definition of intuition? He calls intuition "a memory of the future". A bit like that. I don't know where it comes from but I recognise something and - most of the time - I know what I'm looking for. I feel it. I smell it. I taste it.

So actually quite similar to the way Strauss would have done it, too.

Exactly. That's what I mean when I say I'm still searching for a tune.

Listen to James Dillon's piece for piano solo, Dragonfly, played by Ed Cohen at this year's Proms:

But you're not doing the Maxwell Davies thing of putting folk tunes through a number cruncher?

No. But I do systematise things when I need to. Any interesting piece of music will be a strange balance between a certain abstraction and something much more mysterious. The ratio between those two things varies from piece to piece, even from moment to moment. Sometimes I might layer something that is absolutely mathematically worked out and at other times I'm making deviations, creating a layer that is making deviations from that mathematical layer. Very few things, regardless of what Plato says, exist in the world that are pure. The world is full of impurities which is why it is so endlessly fascinating.

At the moment there are a lot of composers who seem to be composing audience-friendly stuff. Not just the Minimalists. There are people like Judith Weir, whose works have narrative, and Julian Anderson, who has tonal and chant ideas in there. And they're winning audiences and winning friends.

Are they?

Well, I think so.

Well, you're making that statement as if it's a reality and I think it has to be questioned. These are people who are very well, how to put it... they're embraced by the establishment. But are they winning audiences in France and Germany and Italy and Spain? The world is not England for me. It's not dictated by England for me. It never has been. Musically it hasn't. We don't live in that kind of world any more. And my terms of references when I was 20 or 21 were Stockhausen, Xenakis and Messiaen (Xenakis and Messiaen pictured above right), so naturally I began to develop a language that had something to do with their work. I wasn't going to become a little Messiaen or a little Stockhausen but it has something to do with them.

But your brand of Modernism seemed to have it's moment...

[Laughter] And now it's fucked.

Well, recently at the Barbican when they asked various composers to write works for Handel's anniversary, they asked three film composers and three Minimalists: Nico Muhly, Sir John Tavener and Michael Nyman. There wasn't a single Modernist composer. I mean I can understand why someone like you might not respond to Handel but...

Actually I love Handel's operas. I did an opera a couple of years ago [Philomela (2004)] that was heavily influenced by Handel's operas and the Baroque in general.

The journalist said that they were absolutely disgusted by the way the orchestra were yawning in the middle of this performance of my piece. But that happens every time you have an orchestral concert so I didn't even notice it

In what way? Formally or structurally?

Structurally, yes. It's a set of mise en scènes which are tableau-like conflations. It works backwards in a fairly traditional Baroque sense of narrative. The Baroque interests me because of the function of ornamentation in music. I'm fascinated by ornamentation. Ornamentation for me is like a particular type of movement, a flutter. I love it. I don't think ornamentation is something of a surplus. And I've always been fascinated by how you deal with it in a structural way rather than merely as decoration.

Listen to Dillon's solo flute piece, Sgothan:

The flutter in Boulez is everything in many ways.

Yes. That's probably a good example.

What happened with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra? The allegation was that the orchestra behaved disrespectfully during a performance of your work Via Sacra (2000).

First of all, I don't know what you read but most of it is crap. It had nothing to do with what happened. What happened was that I went to a performance in Glasgow of Via Sacra conducted by...

Alexander Lazarev (pictured left).

Lazarev - something Freudian there in forgetting his name. And the performance was routine. Nothing more nor less. But that was as much to do with other factors and the music is complex. These orchestral players usually do too many concerts. And all of a sudden they have to find time to practise [laughs]. That doesn't come into the equation. They usually just turn up.

But I don't blame the orchestra at all. For me it was a routine orchestral concert. I got home, the phone was ringing. It was a guy from The Daily Telegraph or something. What had happened in the meantime was that two reviews had come out in The Scotsman and the Glasgow Herald. And a journalist, not me - it was nothing to do with me; no one had talked to me - had said that they were absolutely disgusted by the way the orchestra were yawning in the middle of the performance, the way they were lying back, laughing and talking to each other. But... [laughter] that happens almost every time you have an orchestral concert so I didn't even notice. I just thought, well, this is what happens - in particular with certain orchestras that don't play much new music, and the RSNO really don't play much contemporary music. So this guy says to me, what did I think about the disgusting behaviour of the orchestra? And I told him that it happens all the time. He goes off and does his copy and he adds bits to it and another newspaper picks up on it and changes it a little but more. And before you know it I was condemning Lazarev! I did say he was unfriendly. Which he was. When I came into the room, he didn't even acknowledge me.

A Russian manner maybe?

Russian pig more like [laughter]. But you know the first thing you should do is say, "Ladies and gentlemen, this is the composer," if nothing else. And I'm standing there like a lemon: does he want me to stand at the front or in the hall? He didn't care. He just wanted to get on with it. Eventually half way through he spoke to me for the first time. That already colours the way an orchestra looks at you. If the conductor has a disrespect, the orchestra have a disrespect. So eventually the story gets to The New Yorker and changes into something else completely.

You could make a film of one of these stadium rock concerts and it would look like Leni Riefenstahl's film of the Nazis

Part of the problem is the way that modern music has decided to withdraw from the symphonic orchestral world and set up its own ensembles to perform its music. How are orchestras meant to understand new music if they don't play it?

You can look at the orchestra in different ways: the orchestra as a museum, as a potential for sonic space, as a memory bank. For me I'm still fascinated by putting together a hundred musicians and exploring that space. You can deal with certain kinds of sonic beams, as Varese said, and projection of sound that you can't play with unless you are working with electronics. And the problem with electronics is that it sounds like shit.

There was a very fine electronic prom of Stockhausen a few years back. It can sound good if it's done well.

But Stockhausen was still working with analogue sound. Analogue sound is so much better than digital. I've tried to work as much with analogue as possible but it's very difficult these days. People don't maintain the equipment.

Modernist composers have sometimes been their worst enemy. Milton Babbitt's (pictured right) essay, "Who Cares If You Listen?", argues that composer-academics should withdraw from public life and that their art should be treated the same as science. I flip and flop on the matter. In some ways it seems a convincing argument.

But we are an emotional art.

You do think that?

Music is an emotional art. You can't deny that.

Someone like Babbitt might have.

But I don't think he'd deny this though. What is buried in the word emotion? Motion. Movement. Sound moves. It's changing. It's an emotional art. The terminology gets distorted with accretions of Romantic nonsense and of course Babbitt was confronting that. These things need to be taken within the moments in time and not as gospel. Babbitt has never particularly interested me as a composer. I don't think he's a bad composer, particularly when you compare him against those other American serial composers; he comes across as interesting. But I'm going to take what he says with a pinch of salt. I know from first-hand experience that he also takes what he says with a pinch of salt. He has a Jewish sense of humour. It's everyone else that doesn't take it with a sense of humour, particularly the reactionary forces in the world.

At any level, do you regret the way that your music has gone in being so complicated and perhaps inaccessible?

I don't think about my music like that. I just move on. Whatever you do is a rich mixture of calculation and mystery. I can't have regrets about something I don't think about. And I don't think about music in that way. It's what I do. I'm a craftsman in sound and I work with my hands. And obviously my brain.

I don't know if all of the New Complexity shared this but there was a notion that if we submit to this "new simplicity", we're surrendering to this consumerist world

But the bands that you talked about that you liked when you were young were commercially successful.

But we don't live in that world any more. People underestimate what a change 40 years has made. First, The Beatles come at a point - it's quite a coincidence - where it's been 15 years since the invention of tape. 1950 is the beginning of tape as a recording medium. 15 years and it reaches a certain level of maturity. There's social factors that expose The Beatles to Elvis Presley etc. But it was also just when Britain was beginning to get over war and money was flowing. Drugs came into it. The history of mechanically recording sound since then has been one of complete and utter decline as far as I'm concerned. Decline in the sense of the populace's relationship with music, which became more and more virtual and less and less real. So it's a very short period. Four or five years. 1966 to 1970. Also in America Led Zeppelin and Captain Beefheart are doing fascinating, really alchemical things with sound. But by 1970 studio engineers had taken over. Multitracking comes in in a big way. 16 track. 32 track. It became so technical. The bands are subject to whatever this engineer feels like he's going to do.

Forty years later we don't live in that era. Part of my walking away from that world was that I knew that it was going to become less interesting. Subsequently for me - and it's a difficult thing to say about your generation - but the last gasp was punk, the Sex Pistols, The Clash, where they really wanted to politically spit in your face. They wanted to say society's fucked, we're all fucked so somebody's got to wake up. Of course the Sex Pistol's propaganda was, "We hate these fat rock stars," referring to Bowie and Glam Rock. But in a curious kind of way I felt instinctively I was walking away from this world. I instinctively felt that part of my work had to have a certain resistance in it, resistance to the way sound was becoming obliterated by recording processes and accelerated by the process of technology.

People bought into that propaganda from the Darmstadt School, and those polemics of Boulez, the talk of bringing the opera houses down. It was silly

The mental danger of a concert was being moved also by more and more spectacular events, where the audiences were almost watching things on TV they were so far away from the stage in these enormous stadiums with their bike shows and firecrackers etc. What was that experience? If you filmed one of those stadium rock concerts, where everyone's asked to put their lighter in the air, it would look like Leni Riefenstahl's film of the Nazis. I find it chilling to watch, truly chilling, because it's about the manipulation of the populace. And they're so easily manipulated by the most banal nothingness, crap. I don't know if all of the New Complexity shared this but there was a deliberate notion that somehow if we submit to this new simplicity, or what [someone] called the "new simpletons", then we're surrendering to this consumerist world.

But throughout history all the music that you like has been commercially pretty successful?

I don't know what you mean by popular. You can't really talk about popular in the modern sense of the word until the late industrial age. Did Bach have an audience? He had a congregation. Did he have an audience? Not in the sense that Handel did. Why are we only now discovering 50, 60, 70 Vivaldi operas that haven't been done for 300 years? Conditions are so different now. You're not comparing like with like. If you talk about popular today you're talking about mass audiences and a mass mindset, which is the tail-end of propaganda and advertising campaigns and massive forms of indoctrination through subliminal means of technology.

But people do want to hear music afresh. And I'm subject to this interest in so-called authentic performances. I think contemporary music shares much more in common with the Baroque period than anything in between, in the sense of the saturation of sound and the complexity of levels.

Except things are codified for the first time in that period in a unidirectional way.

Of course Rameau wrote his Traite de l'harmonie so this is the beginning of so-called functional tonality. But it's not until the mid-19th century with the establishment of the academies and conservatoires that everything begins to be closed down. Technique is defined. And what do you have in modern music? "Extended technique". Who's to say what's been extended?

Yes, they're just sounds.

Exactly. Many of these are secret sounds that instrumentalists know themselves but never get the chance to play in that repertoire. And this is the repertoire that students use to define what repertoire means. The world we live in today has been defined by the academies, which was everything that people like Gustave Courbet was fighting against.

But one theory as to why that early-20th-century period is so exciting for us today is that it provides the familiar and unfamiliar in satisfying quantities. Whereas after this, the idea of rupture takes hold.

People bought into that propaganda from the Darmstadt School [where Dillon, pictured left, taught from 1982 to 1992] and those polemics of Boulez, the talk of bringing the opera houses down and starting afresh and reconstruction and forgetting history. It's silly. These were statements that were meant to shock and they should be taken that way. I still go back to the idea: is it a good or a bad work? Boulez has written two or three good works. Stockhausen's the same. I don't think that changes too much. We talk about The Firebird or Pierrot Lunaire or Ionisation, these pioneering works. But there's a lot of garbage as well. And partly why this early-20th-century period still fascinates is because a lot of things that have been broken up haven't been resolved yet. If it is possible to resolve them at all. Language has become diffracted. There's something more lively to that, more lifelike in that it parallels the complexity of living today. Whereas people tend to listen to Brahms or Rachmaninov, sadly, to escape. It depends on what you think the function of art is. Art has in some ways replaced religion which means it's not simply entertainment. It's trying to approximate to some spiritual emotion. That was the detritus that Darmstadt tried to deny. My generation were left with the mess after that. Do you go into a sort of retreatism or do you say, "No, why am I still fascinated about aspects of this music?" That was my starting point.

But for many the journey to appreciating modern music is a long one.

To understand this music on different levels you really have to know something about classical music, it's true. You need to absorb certain things. But to get it, even if you don't know why you're getting it, it's not necessary. And it's possibly true of all music. I know people who can't stand Baroque music. Cannot stand it. And yet they listen to the whole of the 19th century and possibly even modern music. I'm also aware that I'm one of those people who doesn't think of music in terms of style. Either it has this visceral quality or it's got a cerebral attraction that fascinates me. I don't think we're always consistent. And neither do I think we should be consistent.

- Book tickets to the Glasgow Concert Halls world premiere of James Dillon's Nine Rivers

- Find James Dillon on Amazon

- Check out the rest of the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra's season

- Check out the rest of the season at the Glasgow Concert Hall

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

BBC Proms: Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - defiantly introverted Mahler 5 gives food for thought

Chief Conductor in Waiting has supple, nuanced chemistry with a great orchestra

BBC Proms: Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - defiantly introverted Mahler 5 gives food for thought

Chief Conductor in Waiting has supple, nuanced chemistry with a great orchestra

Dunedin Consort, Butt / D’Angelo, Muñoz, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tedious Handel, directionless song recital

Ho-hum 'comic' cantata, and a song recital needing more than a beautiful voice

Dunedin Consort, Butt / D’Angelo, Muñoz, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tedious Handel, directionless song recital

Ho-hum 'comic' cantata, and a song recital needing more than a beautiful voice

Classical CDs: Dungeons, microtones and psychic distress

This year's big anniversary celebrated with a pair of boxes, plus clarinets, pianos and sacred music

Classical CDs: Dungeons, microtones and psychic distress

This year's big anniversary celebrated with a pair of boxes, plus clarinets, pianos and sacred music

BBC Proms: Liu, Philharmonia, Rouvali review - fine-tuned Tchaikovsky epic

Sounds perfectly finessed in a colourful cornucopia

BBC Proms: Liu, Philharmonia, Rouvali review - fine-tuned Tchaikovsky epic

Sounds perfectly finessed in a colourful cornucopia

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: A Mass of Life, BBCSO, Elder review - a subtle guide to Delius's Nietzschean masterpiece

Mark Elder held back from blasting the audience with a wall of sound

BBC Proms: A Mass of Life, BBCSO, Elder review - a subtle guide to Delius's Nietzschean masterpiece

Mark Elder held back from blasting the audience with a wall of sound

BBC Proms: Le Concert Spirituel, Niquet review - super-sized polyphonic rarities

Monumental works don't quite make for monumental sounds in the Royal Albert Hall

BBC Proms: Le Concert Spirituel, Niquet review - super-sized polyphonic rarities

Monumental works don't quite make for monumental sounds in the Royal Albert Hall

Frang, Romaniw, Liverman, LSO, Pappano, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - sunlight, salt spray, Sea Symphony

Full force of the midday sea in the Usher Hall, thanks to the best captain at the helm

Frang, Romaniw, Liverman, LSO, Pappano, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - sunlight, salt spray, Sea Symphony

Full force of the midday sea in the Usher Hall, thanks to the best captain at the helm

Elschenbroich, Grynyuk / Fibonacci Quartet, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mahogany Brahms and explosive Janáček

String partnerships demonstrate brilliant listening as well as first rate playing

Elschenbroich, Grynyuk / Fibonacci Quartet, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mahogany Brahms and explosive Janáček

String partnerships demonstrate brilliant listening as well as first rate playing

BBC Proms: Akhmetshina, LPO, Gardner review - liquid luxuries

First-class service on an ocean-going programme

BBC Proms: Akhmetshina, LPO, Gardner review - liquid luxuries

First-class service on an ocean-going programme

Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mania and menuets

The Hungarians bring dance music to Edinburgh, but Fischer’s pastiche falls flat

Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mania and menuets

The Hungarians bring dance music to Edinburgh, but Fischer’s pastiche falls flat

Comments

...

I have written bad things