Varèse 360°, Southbank | reviews, news & interviews

Varèse 360°, Southbank

Varèse 360°, Southbank

20th-century hellraiser still delivering the goods

For those of you who think that classical music ends with Mahler - or Brahms just to be on the safe side - that the musical experimentation of the past 60 years was some sort of grim continental joke, an extended whoopee cushion of a musical period that seemed to elevate the garden-shed accident into some kind of art form, you have two people to blame: Adolf Hitler and Edgar Varèse.

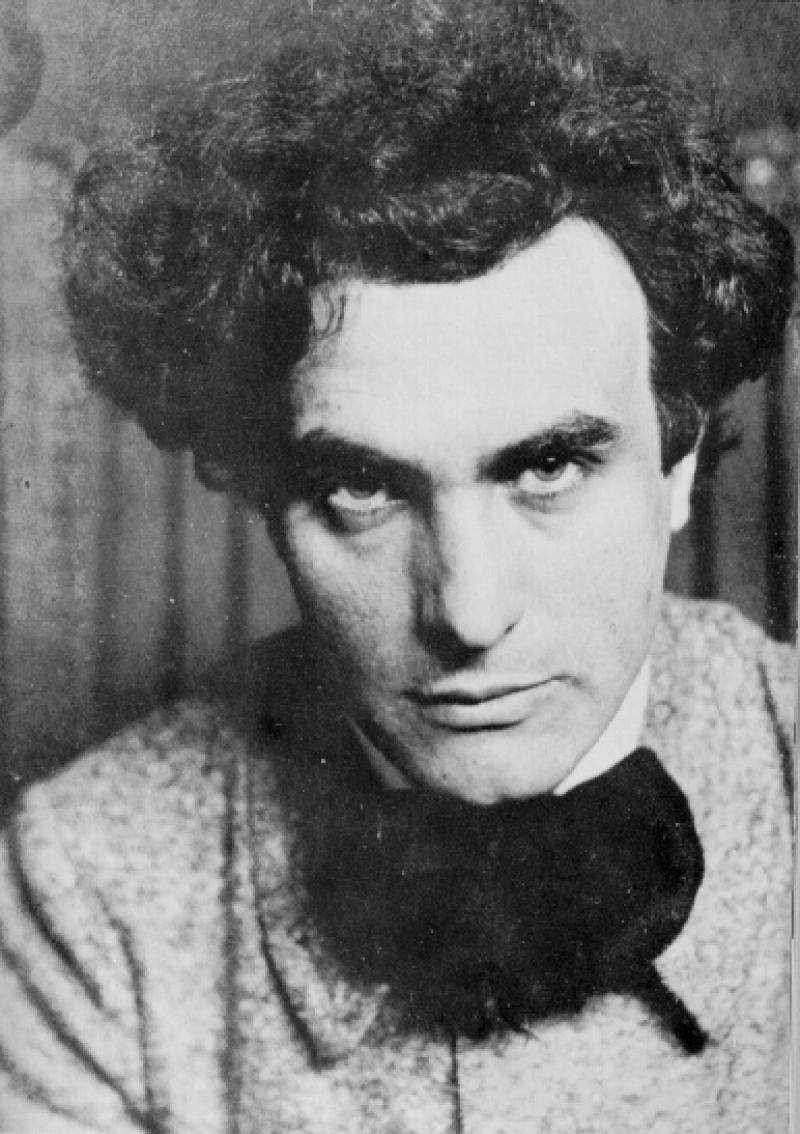

Hitler's influence we shall come to another time. Edgar Varèse's impact was on display this weekend at the Southbank's retrospective, Varèse 360°. Everyone from Frank Zappa to Harrison Birtwistle have doffed their caps to his ideas and ways. The Southbank were showing off his compact oeuvre (all his works can be squeezed onto a double-CD box set), highly prized but seldom performed, over three concerts.

Excitement came from the off with Ionisation, scored for 13 percussion, the first piece to be scored for percussion alone. A ritualistic dance, thrilling to see live, Ionisation is a fanfare to the primordial past and the distant future. It is in many ways an ideal candidate - if we ever needed one - for a Martian national anthem. There's not much of a theme to speak of but there is an abundance of ceremonial weirdness. The smacking pulses, the blocks of maraca, the tubular bell spray (a gravity-less sound somehow), the almighty dissonances, capture, more wholly than any other 20th-century work, the shock of the new. Atherton's band of beaters, moving at a slow, assured, processional pace, stilled the hall into a trance.

But excitement came not just to the ear but to the eye. Before the videowork of Cathie Boyd kicked in, one could happily sit in awe watching these bizarre musical animals congregate and disperse. This was a Serengeti-like display of exotica from the London Sinfonietta. A fantastic fragment of a work, Dance for Burgess, written in the 1940s for a film, seemed to smash through ideas of linearity while still engaging with dance forms. And then there was the extraordinary Déserts, Varese's great breakthrough electronic work, in which a truly bestial orchestra - ever gaining in rhythmic and textural intensity and density - meets a creaking, leaking, fizzing tape, the musical soul of the inanimate.

Of course, interesting instruments do not necessarily beget interesting pieces. And not every offering of Varèse's tiny output worked quite so well. There was Ecuatorial from 1934, perhaps the most outlandishly scored of all his works (it includes a solo bass voice, eight brass, piano, organ, two cello theremins and six percussion), and the most crummy. Its period effects couldn't even be rescued by the stentorian efforts of the great Sir John Tomlinson. And Nocturne, his song for soprano, orchestra and bass choir, fared little better in the hands of Elizabeth Watts and her clown faces.

It's the danger of Varese's genius. Much of it hovers on the edge of madness and mess. When the romantic vision goes right - which is most of the time - it's irresistibly fresh. When it doesn't, it can be more than a little baffling. Still, even in bafflement there is always something of interest in the textures and the methods he deploys to generate movement not through thematic or harmonic development, but through textural jump-cutting (from dry to wet to dusty, say), which was to prove so influential on succeeding generations.

The weekend led up to a climax on Sunday night in the shape of his cataclysmic Amériques (1922), which was being performed by the National Youth Orchestra under Paul Daniel. We were getting the premiere of the original 1921 version, a fascinating draft for what it suggests about his lost late romantic works, but less interesting as a variant on the 1922 version. It includes many moments reminiscent of the old world - wet stringed passages, moments of out-and-out Debussyian fancy, lyricism, an opening straight out of the Rite - that Varèse excises from his later, more violent final version. With these incongruities, this Amériques fell short of the equally gigantic orchestral work, Arcana, which proved to be a more tight and propulsive Leviathan.

The outing of this early Amériques was fascinating nonetheless, particularly when followed up by an encore of Debussy's Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune (summoned up by 17-year-old Joshua Batty, more magically, more subtly than I have ever heard before), which showed how small a step it was from the cumulative blocks of Debussy to those more crazed ones of Varèse - a step encapsulated by his move to New York in 1915.

Sadly, I missed a Sinfonietta performance of his greatest works, the finely whittled-down gems of Intégrales, Octandres and Offrandes from the 1930s, so I move on to a word of praise for the brilliant Cathie Boyd, who was given the impossible task of setting Varèse's aural explosions to film. Wisely, modestly, she kept her hands off many of the works - unlike Gary Hill in the original Amsterdam version of this show, whose efforts were rewarded with expletives and catcalls from a disappointed audience.

Simple lighting effects alone were used for some pieces. The abstract little films of familiar and alien surfaces - a jungle (perhaps), a glassy surface, a laboratory, a rusty railing, all enticingly on the verge of focus - that made it to the walls of the Queen Elizabeth Hall and Royal Festival Hall were models of understatement and refinement: delicate, subtle and inflected with enormous textural variety. They were the perfect complement to the music - never imposing, always adding - a model of filmic interaction that others should take note of.

- Book tickets for the rest of the London Sinfonietta season

- Check out what's on at the Southbank Centre

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Comments

...

...

...