Stuart Jeffries: Everything, All the Time, Everywhere - How We Became Post-Modern review - entertaining origin-story for the world of today | reviews, news & interviews

Stuart Jeffries: Everything, All the Time, Everywhere - How We Became Post-Modern review - entertaining origin-story for the world of today

Stuart Jeffries: Everything, All the Time, Everywhere - How We Became Post-Modern review - entertaining origin-story for the world of today

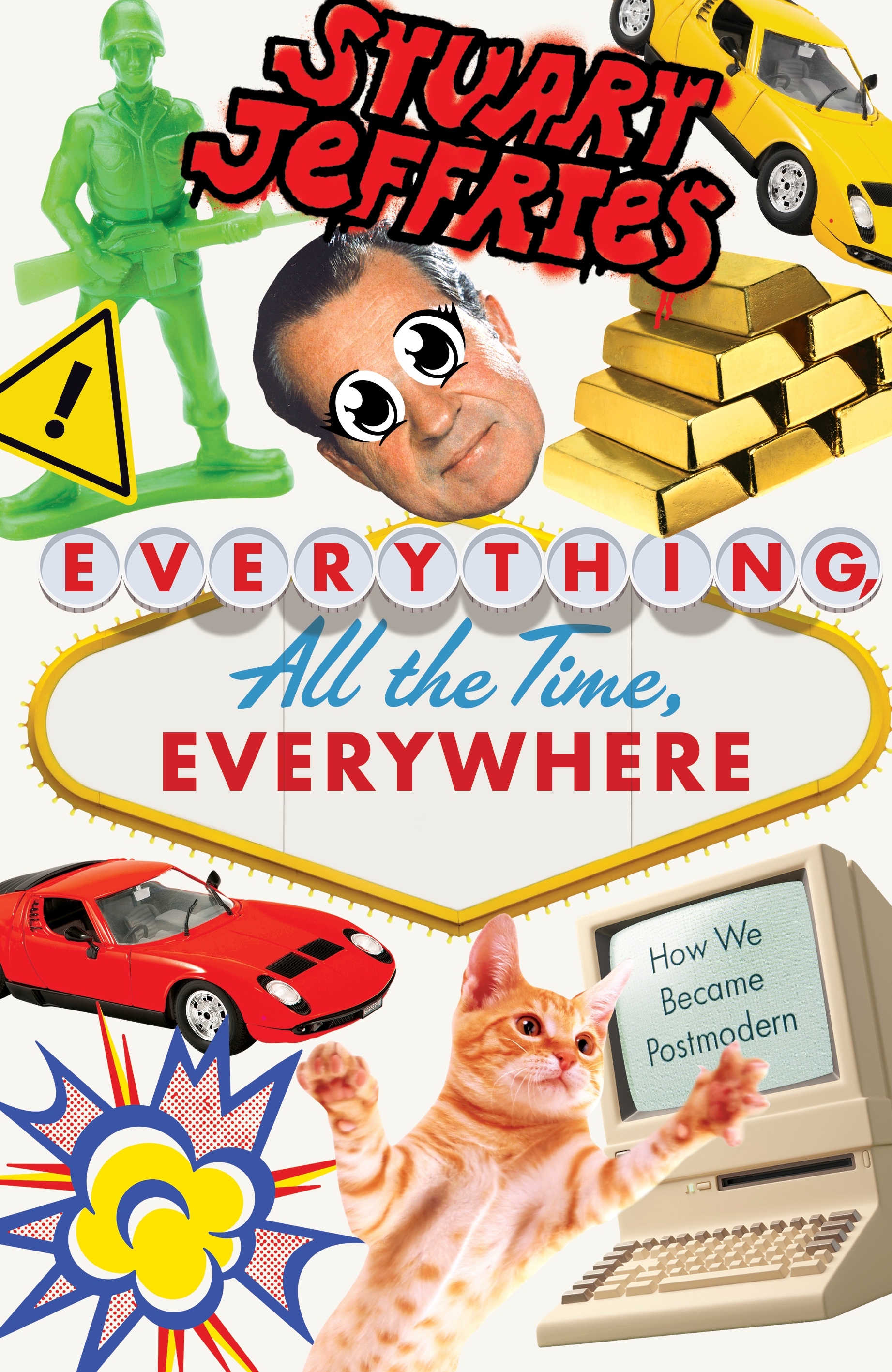

The author of 'Grand Hotel Abyss' covers everything from Margaret Thatcher and Sid Vicious, to Jean Baudrillard and Grand Theft Auto

In his 1985 essay “Not-Knowing”, the American writer Donald Barthelme describes a fictional situation in which an unknown “someone” is writing a story.

“From the world of conventional signs,” Barthelme writes, laying out for the reader this story being written, “he takes an azalea bush, plants it in a pleasant park. He takes a gold pocket watch from the world of conventional signs and places it under the azalea bush. He takes from the same rich source a handsome thief and a chastity belt, places the thief in the chastity belt and lays him tenderly under the azalea, not neglecting to wind the gold pocket watch so that its ticking will at last awaken the now-sleeping thief.” Then, Barthelme continues, “he borrows a pair of seniors, Jacqueline and Jemima, and sets them to waking in the vicinity of the azalea bush and the handsome, chaste thief".

In his readiness to “take” and “borrow”, Barthelme’s fictionalised author resembles Lance Taylor, better known as Afrika Bambaataa, founder of the Zulu Nation. Inspired by the 1964 film Zulu, Bambaataa started out as a DJ in New York’s Bronx, sampling “from Caribbean soca, African music and even German electronica” as he sought to deliver an eclectic edge to his bloc party throwdowns. Bambaataa, according to Stuart Jeffries’s latest book, Everything, All the Time, Everywhere: How We Became Post-Modern, was a purveyor of “postmodern-pastiche”, churning out new music from the “junk, rubble, aerosol cans and old records”, or whatever else happened to be lying around, transforming the old and straightforward into something new, subversive, and originally un-original. In so doing, Bambaataa displayed an attitude towards music akin to that which Robert Venturi, along with his wife and partner Denise Scott Brown, brought to architecture: “a resource to be plundered, a supermarket of styles” from which the pair returned “with trolleys full of material to rebuff modernist aesthetics”. The task of the artist, for Brown and Venturi, was to liberate art from the shackles of a single mode, an ethos on full display in their design for the Sainsbury Wing of London’s National Gallery.

“The world enters the work as it enters our ordinary lives, not as world-view or system but in sharp particularity,” Barthelme went on to write in "Not-Knowing". It is with such particularity that Jeffries proceeds. Bambaataa and Venturi are unlikely partners; their conference here is symptomatic of Everything’s bricolage of conventionally "high" and "low" culture that is itself postmodern. Each of Jeffries’s chapters select three more examples from postmodernism’s diverse portfolio as the journalist and author pieces together a sort of chronological origin-story for the world of today, giving rise to such intriguing juxtapositions as Margaret Thatcher and Sid Vicious, or Chris Kraus and Grand Theft Auto. It is a story that begins in 1972, with the collapse of the Bretton Woods system. Referred to as the “Nixon Shock”, the policy decisions taken by the American president eradicated the basis for Keynesian economics, precipitating the “globalised, hyperconnected world” we know today and, in the privilege given to transnational capital flows, Jeffries argues, “destroyed the social-democratic egalitarianism of advanced industrial nations”.

“The world enters the work as it enters our ordinary lives, not as world-view or system but in sharp particularity,” Barthelme went on to write in "Not-Knowing". It is with such particularity that Jeffries proceeds. Bambaataa and Venturi are unlikely partners; their conference here is symptomatic of Everything’s bricolage of conventionally "high" and "low" culture that is itself postmodern. Each of Jeffries’s chapters select three more examples from postmodernism’s diverse portfolio as the journalist and author pieces together a sort of chronological origin-story for the world of today, giving rise to such intriguing juxtapositions as Margaret Thatcher and Sid Vicious, or Chris Kraus and Grand Theft Auto. It is a story that begins in 1972, with the collapse of the Bretton Woods system. Referred to as the “Nixon Shock”, the policy decisions taken by the American president eradicated the basis for Keynesian economics, precipitating the “globalised, hyperconnected world” we know today and, in the privilege given to transnational capital flows, Jeffries argues, “destroyed the social-democratic egalitarianism of advanced industrial nations”.

In his previous book, Grand Hotel Abyss: The Lives of the Frankfurt School, Jeffries turned the spotlight onto the human side of some of the 20th century’s most obscure intellectuals, and in doing so made their concepts legible. Here, he faces the opposite task: in holding a mirror to a familiar world, Everything looks to reveal hidden complexities. The economic paradigm that Nixon inspired is as integral to Jeffries’s account of postmodernism as is Madonna’s Like a Virgin (1984) or Jeff Koons’s "Rabbit" (1986). Ours is a “schizophrenic” era, of one-click ordering and instant gratification, of Deliveroo drivers and zero-hours contracts. It is also an era, following the works of Barthes, Foucault and Lyotard, of “language games”, in which fixed meaning is absent, and the so-called “meta-narratives” of history and science are refuted, supplanted instead by a plurality of competing, equally valid claims. Another former president, Donald Trump, is not so much a cause of this postmodern dystopia as a symptom: who, in the shape of 1980s New York, found a city as “amenable” to him as was that of Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho (1991) to the violent sexual fantasies of its protagonist, Patrick Bateman. Shifting between matters real and virtual in this way, Jeffries showcases a natural ease that ensures Everything is eminently readable, without eliding the difficulties that are so key to its intrigue – whether grappling with the complexity of Derrida’s “metaphysics of presence” or recounting the debates between queer and feminist theories.

Barthelme, although absent from Everything’s account of postmodernism, exhibits in the distancing effect of his writer-conceit the irony that is, to Jeffries, the movement’s “go-to rhetorical stance”. But "Not-Knowing" concludes not without Barthelme first shedding that rhetoric, stepping out from behind the veil to praise literature’s “meliorative” powers, its aim “finally to change the world”. Jeffries likewise concludes his mediation with an afterword but, entitled “Ghost Modernism”, it charts in a different direction, away from the fiction of playful pluralism to a real world defined by a diminishing state, increasing corporate control, and self-willed technological domination. “What was supposed to be a jaunty antidote to modernist solemnity,” he writes of Islington's colourful Highcroft council estate, “has become sad, like a cake left out in the rain.” It is in the sadness of our contemporary world, one stripped of its “thoughtfulness and kindness”, that Jeffries finds postmodernism’s defining legacy. Everything is not a message of hope, only an answer to a question: how did we get here?

- Everything, All the Time, Everywhere: How We Became Post-Modern by Stuart Jeffries (Verso, £20.00)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Jessica Duchen: Myra Hess - National Treasure review - well-told life of a pioneering musician

Biography of the groundbreaking British pianist who was a hero of the Blitz

Jessica Duchen: Myra Hess - National Treasure review - well-told life of a pioneering musician

Biography of the groundbreaking British pianist who was a hero of the Blitz

Comments

You reference the 'Brutalist

Hi Ian,Thanks for your

Hi Ian,

Thanks for your comment. It is indeed an error. Jeffries compares the declining fate of the Highcroft estate to crumbling brutalist concrete, but the estate itself is not brutalist. The correction has been made.

Best,

Daniel