Wole Soyinka: Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth review – sprawling satire of modern-day Nigeria | reviews, news & interviews

Wole Soyinka: Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth review – sprawling satire of modern-day Nigeria

Wole Soyinka: Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth review – sprawling satire of modern-day Nigeria

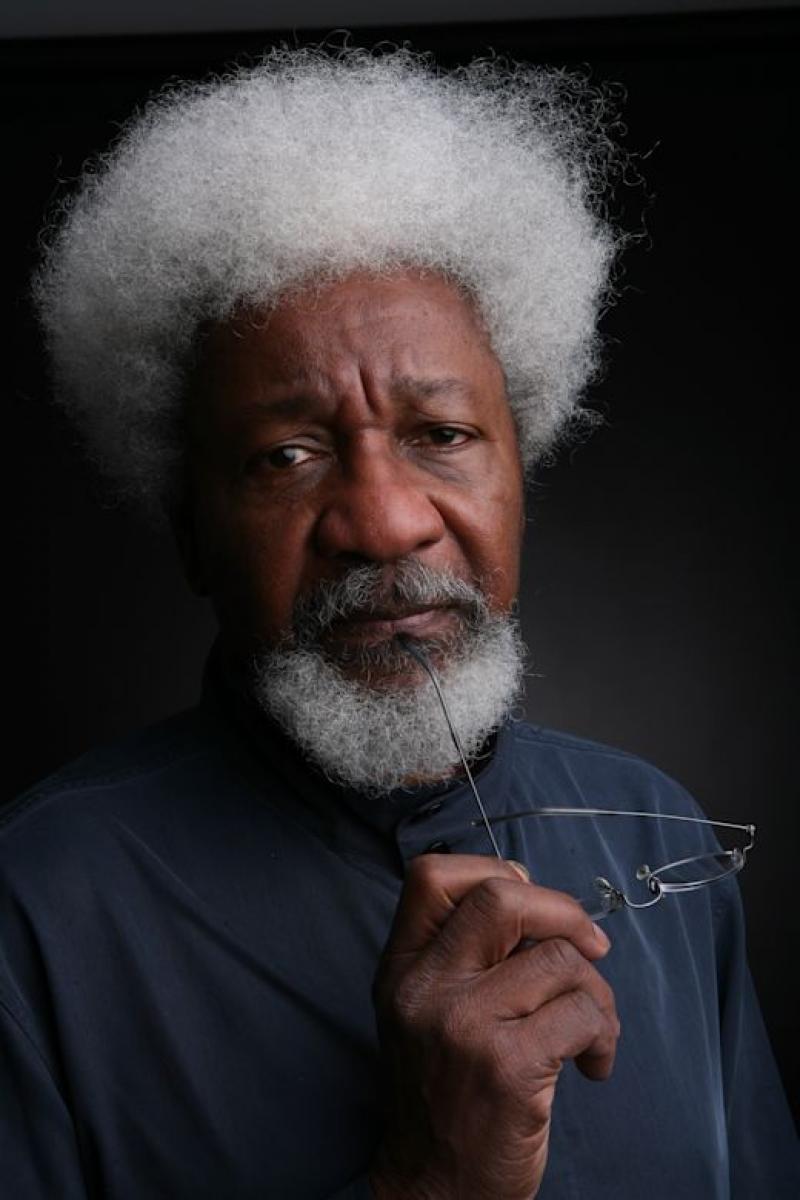

The Nobel Laureate ends a 48 year wait for his third novel

Eight-years passed between the publication of Wole Soyinka’s debut novel, The Interpreters (1965), and his second, Season of Anomy (1973). A lot happened in the interim.

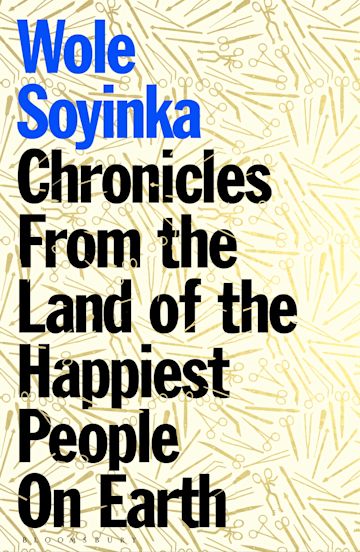

Consider, then, how much has transpired during the forty-eight years wait for Soyinka’s third novel, released this year. Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth (2021) condenses nearly five decades’ worth of brewing anger and activist sentiment into a dense and sprawling text, which loosely assumes the shape of an amateur detective drama. The Land in question is a slapstick caricature of Nigerian society in several degrees of chaos, its landscape one of “elephant-trap potholes”, “military-assisted police extortion checkpoints”, and “kamikaze drivers drugged to the gills on all brands of affordable hallucinogens”. It is a world of surface over substance: under the rule of the “People on the Move Party” (POMP), daily life revolves around a barrage of Orwellian celebrations of false virtue, including “Yeoman of the Year” and “P.A.C.T.” (the “People’s Award for the Common Touch”), with nominees such as the politician who once drank from a calabash, and another, “Ubenzy’, whose name has been self-styled after Mercedes Benz: “the status symbol after independence before the motor car was displaced by the private jet”. This is satire, with a thin veil.

Amid the vice, the plot of Chronicles revolves around the mysterious “Human Resources”, a black-market organisation dealing in the trade of human spare parts, with ties to a web of high-profile figures including the shadowy preacher Papa Davina, and the prime minister, Sir Godfrey Danfere. There is a sleuth on their tail, however: the surgeon Dr. Kighare Menka, a reluctant member of Nigeria’s celebrity class, on account of his work tending to the victims of a Boko Haram massacre. Menka is approached by a group of representatives from Human Resources, in the hope that he will contribute to their supply. Refusing, he instead commits himself to the unveiling their crimes. In this, Menka is aided by his “bosom friend”, the effusive engineer and entrepreneur Duyole Pitan-Payne – yet another to enjoy celebrity status, following his recent appointee to the United Nations.

When Soyinka was presented with the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1986, he became the first African laureate in the process. For those unfamiliar with the achievements of this celebrated poet, playwright, and novelist, however, Chronicles offers a poor sample of Soyinka’s work. Menka’s investigation falls through almost as soon as it has begun – an indication of insurmountable effort required to recover Nigerian society, but resulting also in a novel that boasts a surprising lack of direction, despite the hundreds of pages given over to description and context. Along the way, characters fall into irrelevance, others are kept frustratingly distant by prose that is unnatural, even disorientating. Consider this line, commenting upon a funeral procession: “It would appear that it was not merely stentorian grieving that proved contagious among that motley assemblage of the bereft”. Nor even can basic descriptions escape Soyinka’s thesaurus: Menka’s face, he tells us, is “lightly scarified”. Insignificant in isolation, yet the frequency of these moments is relentless. Their sum is to disrupt all readerly momentum, leaving Chronicles with the feel of a thing unfinished.

When Soyinka was presented with the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1986, he became the first African laureate in the process. For those unfamiliar with the achievements of this celebrated poet, playwright, and novelist, however, Chronicles offers a poor sample of Soyinka’s work. Menka’s investigation falls through almost as soon as it has begun – an indication of insurmountable effort required to recover Nigerian society, but resulting also in a novel that boasts a surprising lack of direction, despite the hundreds of pages given over to description and context. Along the way, characters fall into irrelevance, others are kept frustratingly distant by prose that is unnatural, even disorientating. Consider this line, commenting upon a funeral procession: “It would appear that it was not merely stentorian grieving that proved contagious among that motley assemblage of the bereft”. Nor even can basic descriptions escape Soyinka’s thesaurus: Menka’s face, he tells us, is “lightly scarified”. Insignificant in isolation, yet the frequency of these moments is relentless. Their sum is to disrupt all readerly momentum, leaving Chronicles with the feel of a thing unfinished.

This is not to say that Chronicles roams without merit. Death announces itself into the novel like “a sinkhole opened up in the midst of a crowded intersection”, precipitating a welcome shift in focus away from Soyinka’s Nigerian satire, and towards a more nuanced assessment of the tensions that inhere between local traditions and culture and an imperious West. It is the latest chapter in a career-long engagement with such themes, and a reminder of the work that secured Soyinka's place at the high table of contemporary writing.

- Chronicles of the Happiest People on Earth by Wole Soyinka (Bloomsbury, £20.00)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Add comment