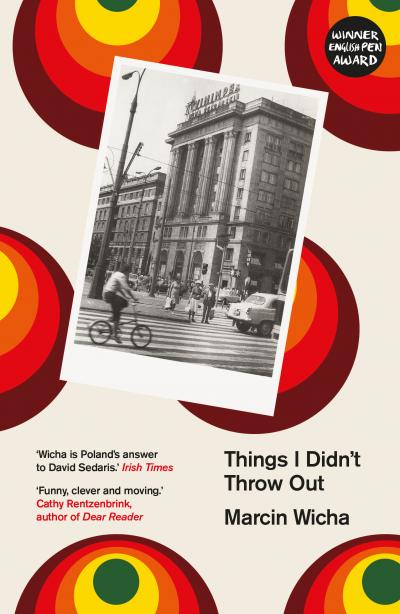

Marcin Wicha: Things I Didn’t Throw Out review - the stories told by stacks of stuff | reviews, news & interviews

Marcin Wicha: Things I Didn’t Throw Out review - the stories told by stacks of stuff

Marcin Wicha: Things I Didn’t Throw Out review - the stories told by stacks of stuff

Connecting a mother's helpless love of things with questions of presence and personhood

Marcin Wicha’s mother Joanna never talked about her death. A Jewish counsellor based in an office built on top of the rubble of the Warsaw Ghetto, her days were consumed by work and her passion for shopping. Only once did she refer to her passing, waving her hand around her apartment and asking Wicha: “What are you going to do with all this?”

Later, the bereaved Wicha sifts through “all this”: black binders full of recipes clipped from magazines, chargers for old phones, inflatable headrests, yellowed newspapers and ballpoint pens. The stacks of stuff remind him of past conversations, and Joanna’s voice returns to fill the emptying room. Things I Didn’t Throw Out is a sharp and funny memoir about a Polish family living through the 20th century, but it is also about the fragments that people leave in our lives in both their words and their objects.

In his cult work of theory Art and Agency (1998), the anthropologist Alfred Gell put forward an interpretation of art as a record of presence. Gell proposed that art is not a symbol or a sign, but contains the remnants of people’s actions, and – therefore – should be considered part of the social field rather than the aesthetic. The implication of his work is that people do not just consist of their bodies, but are also present in the marks they leave on the material world. Gell called this idea “distributed personhood”. He explained “[a] person and person’s mind are not confined to particular spatio-temporal coordinates but consist of a spread of biographical events and memories of events, and a dispersed category of material objects, traces and leavings”.

By writing Johanna’s biography through her “objects, traces and leavings”, Things I Didn’t Throw Out is an experimental study of personhood as it is distributed through stories, memories and personal possessions. A storehouse of anecdotes, the book is strikingly reminiscent of Natalia Ginzburg’s Family Lexicon (1968), an autobiographical novel about Ginzburg’s extended family set against the rise of fascism in Italy between the 1920s and 1950s. Family Lexicon is made of noisy family scenes where sayings, jokes, put-downs and songs are repeated, each time acquiring a further layer of meaning. In the preface, Ginzburg described these phrases as “our Latin, the dictionary of our past, they’re like Egyptian or Assyro-Babylonian hieroglyphics.”

By writing Johanna’s biography through her “objects, traces and leavings”, Things I Didn’t Throw Out is an experimental study of personhood as it is distributed through stories, memories and personal possessions. A storehouse of anecdotes, the book is strikingly reminiscent of Natalia Ginzburg’s Family Lexicon (1968), an autobiographical novel about Ginzburg’s extended family set against the rise of fascism in Italy between the 1920s and 1950s. Family Lexicon is made of noisy family scenes where sayings, jokes, put-downs and songs are repeated, each time acquiring a further layer of meaning. In the preface, Ginzburg described these phrases as “our Latin, the dictionary of our past, they’re like Egyptian or Assyro-Babylonian hieroglyphics.”

When Wicha’s extended family gets together in Things I Didn’t Throw Out, they also rehash the past, sharing “the golden oldies, stories recited year after year, like prayers” (including the one “About how in Spain the bread is all crust”). The characters in the anecdotes appear briefly: they speak one line or do something funny, then disappear. “An anecdote is a single point”, Wicha observes. “Our [family] history consisted of dispersed points.” This creates a sprawling family memoir, where the tiny fragments of people long gone are re-animated at the dinner table, given new life through their preservation in collective memory.

Ginzburg well understood that any family is created from friction, conflict, and contrast. In Things I Didn’t Throw Out, tension, too, is a vital part of the family language. Joanna’s husband Piotr is quiet, steady and unmoving; Joanna is not. She is witty and precise, and delights in any opportunity to create an argument with a clerk, shop worker or receptionist. She teases her son constantly. Whenever Wicha brings up a schoolmate that he does not like, Joanna makes a point of saying that he is “a lovely boy”.

Family stories acquire their own history through the ways they are created, re-told and inflected by the emotional tone of the interactions they accompany. In Things I Didn’t Throw Out, Wicha handles more conventional political history with great delicacy. World War Two, the Holocaust, communism and its end in 1989 all happen on the edges. Time moves slowly and strangely around Joanna; it is creaking, almost tectonic. For much of the 20th century, Polish people, especially Jews, lived with curbs on their political agency. Given this context, it makes sense that Wicha favours the language of ecology to describe change over time. Joanna’s bookshelves show a “geological cross-section” of coloured spines spanning the 40s to the 90s. Polish people’s indifference to communism wears down the regime “like sand”. “Politics, our ... English weather,” Wicha quips after one visit to Joanna.

Instead, the weather comes into Joanna’s Warsaw apartment indirectly. Things pour into the house and accumulate in cabinets. Leafing through Joanna’s files of recipe clippings from the 60s (a period of supply shortages in the communist economy), Wicha finds recipes for Czech cabbage pie, Swedish apple pie and Swiss casserole with Emmental cheese. By contrast, the final page in the book contains a list that reads: lasagne, mozzarella cheese, fennel, pears with grana cheese – all the new offerings of post-Soviet era capitalism. To read Things I Didn’t Throw Out through the theory of “distributed personhood” is to perceive how the things Joanna cooked and ate reveal her thinking process: her creative adaptation of Poland’s unfolding political history into the daily acts of living.

For Joanna, a room full of stuff represents a place where her family has all of their needs met

In the crevices and corners of the apartment, time is not always on the advance. In the bottom of one drawer, it has stopped: Wicha finds an unopened packet of sugar distributed as part of the American aid efforts after the liberation of Warsaw in 1944. Joanna’s helpless love of things, and her reluctance to throw anything away, might make her a hoarder. In Possessed: A Cultural History of Hoarding (2021), Rebecca L Falkoff observes that the definition of “hoarding” hinges on whether or not the hoarder’s consumption is “rational” according to the logic of capitalism. Certainly, when Wicha attempts to sell Johanna’s books, he is unsuccessful. The Warsaw book buyers that he approaches see no element of curation, nothing to make the contents of her bookshelves a conscious “collection” rather than a random accumulation.

Yet, there are other logics that direct how Joanna consumes, and therefore, how she thinks. In one passage, Wicha recalls:

“I’m working on my immortality”, she’d say. She was composing others’ memories so that one day the children would realise that the hours spent in her flat, among illustrated books and films on VHS, were their only moments of perfect calm.

By constantly adding to her apartment, Joanna attempts to author her own legacy, intentionally planting memories of herself in the minds of others. What is more rational than the need for love, security and safety? Things I Didn’t Throw Out is brilliant because it presents an account of consumption (perhaps hoarding) that privileges psychic and emotional needs – both of which quietly drive markets through dreams, fantasies and desires. For Joanna, a room full of stuff represents a place where her family has all of their needs met, in a cocoon away from the weather outside.

Still, families are made up of silences as well as stories, of empty spaces where things ought to be. As Wicha conducts his archaeology of Joanna’s life, he inevitably unearths what has been buried. Throughout Things I Didn’t Throw Out, Wicha’s Jewish family make little mention of the Polish concentration camps: Auschwitz, Treblinka and Majdanek. In fact, their Jewishness is deliberately elided. Making fun of his Polish people’s reticence on the subject of Jewishness, Wicha introduces Joanna as having “the, ahem, look. The look of someone of, ahem, ahem, descent”.

Only when Joanna is sick in bed at the end of her life does the Holocaust surface. She is gripped by anxieties surrounding the administration on which the persecution of Jews relied: the lists, documents, trains, pushing crowds and the abandoned “bundle[s] with remnants of belongings”. This revelation throws Joanna’s love of shopping into greater relief. As a young boy, Wicha accompanied Joanna on shopping trips where she showed pig-headed determination when it came to tracking down rare goods, and artfully took on shopkeepers reticent about their stock. Perhaps, in shopping, Joanna had found a system that she could play with and over which she had a level of control.

Things I Didn’t Throw Out is a book about making sense of history, both the personal and political. It argues that when you live with tragedy and loss, all you can do is to make a home out of the detritus left behind: the leavings and fragments of those who have been lost.

- Things I Didn't Throw Out by Marcin Wicha, translated by Marta Dziurosz (Daunt Books, £9.99)

- More book reviews and features on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Comments

The memoir is engaging and

The memoir is engaging and perceptive, catching Joanna's feisty and combative nature. Wicha captures the close connections as well as the tensions in family life with affection and humour. The desperate shortages in communist society;the traumas of Polish and Jewish experience in WW2; the shame (and shamefulness) of ant-semitism and its re-emergence in the 60s ; the small but heroic defiance and personal resilience of Joanna (alongside her vulnerabilities) are all explored with insight and humour. If anything, all the more devastating for the understated and deadpan presentation. Ultimately the material detritus alongside the fragments of memories are all that remains - as Wicha writes "that's all". But even then, it doesn't define the person (as he says in his introduction ). I found this a moving, engaging and informative memoir, infused with Wicha's love for his mother. Well worth sharing with others - so thanks for posting the review. So sad to learn that Martin Wicha died recently.

one point though: Why "Polish concentration camps"? Fact is that they were set up by rage occupiers i.e. the Nazi Party or, if you want to apportion nationality to the camps, Germans.