And so John Adams’s residency with the London Symphony Orchestra reaches its finale – a brisk allegro of a concert with a cheeky coda in the form of the composer’s latest orchestral work, Absolute Jest. One of contemporary music’s most articulate advocates, Adams here swapped pen for baton in a beautifully programmed concert that took a postmodern road-trip across 20th century musical America, guiding listeners along the highways of Copland’s Appalachian Spring and Ives’s Country Band March and off-road for Elliott Carter’s Variations for Orchestra.

Ives’s Country Band March is an irrepressible concert opener – a joyous, big-as-Texas musical grin that is far too busy smiling to remember what irony is. By rights this vignette on provincial music-making should be insufferably smug, but there’s so much affection, so much first-hand knowledge mixed in with the mockery that even cue-missing, note-splitting, small-town musicians can join in this joke at their expense. The LSO gave everything Adams asked of them, romping into head-on collisions and sidling their way niftily out of disasters, in a slapstick routine where every pratfall got its laugh.

There was no faulting the persuasive dynamism of the St Lawrence members, nor the LSO’s textural nuance

Copland’s Appalachian Spring is a world away in temperament, but shares Ives’s magpie fascination with America’s musical history, climaxing memorably in a set of variations on the traditional Shaker hymn, "Simple Gifts". In its original chamber scoring the ballet has a translucent clarity of texture which Copland’s full orchestral treatment struggles to sustain, but which can be more than compensated for by the generous, swinging collisions of strings and brass in the initial Allegro and the later bride’s dance. Despite Adams’s poised tempos, the former was more scrum than dance thanks to the determination of the LSO brass to play behind the beat (shades of Ives), before seemingly waking up and getting ahead of everyone. Rustic trombones, defiantly refusing to play legato, completely missed the transfiguring point of their variation, but some delicate works from flutes, clarinet and strings helped us cling to Copland’s narrative.

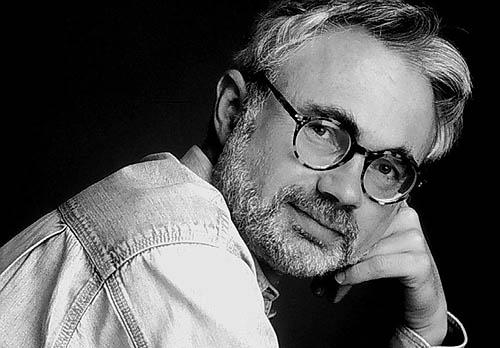

The death of Elliott Carter (pictured right) last November left American contemporary music without its eldest and most distinguished statesman. In an almost 80-year career this impossibly prolific composer produced a catalogue of large-orchestral works, but is still much more likely to be represented in this country by his chamber compositions. A chance to hear his ecstatic, contrarian Variations for Orchestra is rare, and if the wilful complexity of their design resists any attempt to assimilate them aurally at a first hearing, then that is by no means a failure. It eschews conventional theme-and-variations form in favour of a much more anarchic structure that takes three themes on a 10-movement journey through a musical hall of mirrors.

The death of Elliott Carter (pictured right) last November left American contemporary music without its eldest and most distinguished statesman. In an almost 80-year career this impossibly prolific composer produced a catalogue of large-orchestral works, but is still much more likely to be represented in this country by his chamber compositions. A chance to hear his ecstatic, contrarian Variations for Orchestra is rare, and if the wilful complexity of their design resists any attempt to assimilate them aurally at a first hearing, then that is by no means a failure. It eschews conventional theme-and-variations form in favour of a much more anarchic structure that takes three themes on a 10-movement journey through a musical hall of mirrors.

Let go of expectations and rational processes, and Carter’s work becomes an exercise in juxtaposition. Contrasting elements constantly find themselves held in tension, whether horizontally in melodic shapes, or vertically in textural encounters. Brittle little stabs of untuned percussion flicker against a sustained melody for solo violin, and fugal impulses decay into explosive fragments. The LSO made a good case here, approaching the work with the narrative focus that their Copland hadn’t quite grasped, convincing a Sunday night audience of its beauties as well as its uncompromising technical accomplishment.

The last word in an evening that saw European musical myths written and rewritten for the American experience, Adams’s Absolute Jest is the composer’s homage to Beethoven. Commissioned for the 100th anniversary of the San Francisco Symphony last year, the work unusually combines orchestra with string quartet – here the mighty St Lawrence String Quartet (pictured below), who premiered the work – in a collage that rips out fragments from the late Beethoven quartets – the scherzos from Op 131 and 135 – as well as the Grosse Fuge and the Ninth Symphony among others, before deconstructing and reassembling them as cells in a maximal piece of Adams minimalism.

The title makes an obvious nod to David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, but there are none of Wallace’s footnotes and false starts here in a single movement concerto that has a clear sense of trajectory. Adams’s bits of Beethoven aren’t Infinite Jest’s cultural detritus, nor even Eliot’s fragments shored against our ruin, but polished musical gems strung on a gilded thread. This is both the joy of a work that gleams with skill and technical thrill, and its limitation. When Stravinsky chose his musical sources for Pulcinella he worked only with his musical inferiors, while Adams goes up against a titan. The two composers wrestle; at times Beethoven is uppermost and at times Adams, and while the tussle is an attractive scrap of motor rhythms and carefully paced arcs of energy, it’s not great, authentic Adams.

The title makes an obvious nod to David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, but there are none of Wallace’s footnotes and false starts here in a single movement concerto that has a clear sense of trajectory. Adams’s bits of Beethoven aren’t Infinite Jest’s cultural detritus, nor even Eliot’s fragments shored against our ruin, but polished musical gems strung on a gilded thread. This is both the joy of a work that gleams with skill and technical thrill, and its limitation. When Stravinsky chose his musical sources for Pulcinella he worked only with his musical inferiors, while Adams goes up against a titan. The two composers wrestle; at times Beethoven is uppermost and at times Adams, and while the tussle is an attractive scrap of motor rhythms and carefully paced arcs of energy, it’s not great, authentic Adams.

There was no faulting the persuasive dynamism of the St Lawrence members, nor the LSO’s textural nuance, but listening to Adams’s work it was hard not to remember that Wallace’s working title for Infinite Jest was A Failed Entertainment. Absolute Jest, by contrast, is a supremely successful entertainment – a glossy marriage of chunky minimalism and classical complexity. Adams has wit and invention in abundance, but Beethoven still has the last laugh here.

Add comment