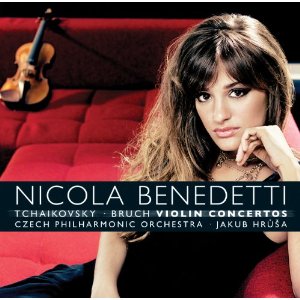

It’s not often that a serious musician goes into the recording studio to play requests. But as the closest that classical music strays to The X Factor (unless you count Paul Potts), Nicola Benedetti has a different kind of relationship with audiences. At the age of 23, several years into a professional career which began at 17 with a hugely popular victory in the BBC’s Young Musician of the Year competition, Nicola Benedetti has released a CD which lacks an agenda or a slant. There’s no new work, no transcriptions or retrieving unknown bits and pieces from dusty archives. Instead she recorded two of the most popular concertos in the repertoire.

“A lot of the public that I speak to after concerts have been asking about the big Romantic concertos,” she says. “When was I going to make a recording of them? You look at other CDs and a lot of the couplings of concertos are amazingly unimaginative. But I’ve been performing Tchaikovsky and Bruch quite a lot, and I just thought, why not? I’ve never done a straight, predictable CD.”

The recording, with Jakub Hrůša and the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, marks a significant moment in Benedetti’s development. Youthfully blessed with talent, she has profited from the accelerated advancement of television exposure. Armed with looks and frocks, a six-album deal with Deutsche Grammophon followed, plus a gruelling round of concerts and transatlantic stardom. It should have been everything a precocious fiddler could dream of. But something wasn’t quite right. So the carousel came to a halt while Benedetti went to study with two new teachers, both Eastern Europeans based in Vienna, and took the time to learn some new repertoire. The change, as it does with many a maturing pop starlet, took the form of fist-shaking defiance at her Svengalian handlers.

The recording, with Jakub Hrůša and the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, marks a significant moment in Benedetti’s development. Youthfully blessed with talent, she has profited from the accelerated advancement of television exposure. Armed with looks and frocks, a six-album deal with Deutsche Grammophon followed, plus a gruelling round of concerts and transatlantic stardom. It should have been everything a precocious fiddler could dream of. But something wasn’t quite right. So the carousel came to a halt while Benedetti went to study with two new teachers, both Eastern Europeans based in Vienna, and took the time to learn some new repertoire. The change, as it does with many a maturing pop starlet, took the form of fist-shaking defiance at her Svengalian handlers.

“I’m not listening to anyone telling me, ‘Your career has to go at this pace or else you might fall behind the other competition,’ and all this rubbish which doesn’t do you any good,” she told me a year ago. “I’m just listening to myself and I’m very clear with how much I can do and always putting my development as a musician before the development of a career. Which is a difficult thing to do when there are so many people telling you what opportunities you could be missing. But the difference in my happiness is really incredible. I’m sticking to this way.”

It’s not that the work won’t continue, she tells me a year on. “Because of my start with the violin, the fact that I had to change a lot of technical things when I was 10 and I didn't have the perfect violin set-up from a young age, it means that I am constantly having to recontrol my technique, recontrol my playing. That will be with me the rest of my life. There are certain things which if you haven’t done by 11 you will constantly have to control. Fair enough, no problem. But it means sometimes I can have the absolute perfect environment and something physically in me can still change. And it can be slightly unpredictable for me exactly how I’m going to feel when. Tension can creep back into my muscles without me having encouraged it whatsoever. And it’s something so subtle that it’s quite difficult to get rid of. You would think I had had enough time and experience to know where it comes from, to try and trace it back. I’ve spent enough hours of the day to work this out, and I would say that 98 per cent of the time I know exactly why I am the way I am and I know what to do about it and in general my whole level of playing and level of competence has really shot up since I took that time off and really did what I had to do. But it’s ongoing.”

Nicola Benedetti plays The Lark Ascending:

The first result of that change of emphasis was Fantasie, released in 2009. Where previous releases have been calculated to prove her serious intent – featuring works by Szymanowski, Mendelssohn, Tavener, Macmillan – in Fantasie she played to the grandstand with a tracklist mingling harum-scarum gypsy-tinged showpieces and compositions of meditative simplicity.

Among the latter was The Lark Ascending, which Benedetti has since luminously performed in her BBC Proms debut. It’s intriguing to hear this distillation of Englishness interpreted by a Scot of mostly Italian extraction and taught by Eastern Europeans who scarcely know the piece. “It’s not nearly as famous outside the UK. A lot of people say, ‘It’s so beautiful. How come we didn’t know about it beforehand?’ I tried to just see it in context of Vaughan Williams’s music rather than approaching it as one of the most popular pieces and how can I make it different? It’s a piece that has to breathe, that has to feel so natural and have a natural flow and very open sound with a feeling of air and nature. I think it can suffer from having too much done to it.”

And so to her headlong dive into the Romantic repertoire. In the violin concerti by Bruch and Tchaikovsky, Benedetti has chosen to tackle those compositions against which all violinists must test themselves. Now seems the appropriate moment. For one, she is no longer quite the innocent abroad who gave such a delicate interpretation of the Mendelssohn. “It sounds quite polite and careful in comparison to how I’ve been performing it since,” she says. “But there are lots of things that are a little bit vulnerable about the recording which I think really suit the youth of the piece.”

And so to her headlong dive into the Romantic repertoire. In the violin concerti by Bruch and Tchaikovsky, Benedetti has chosen to tackle those compositions against which all violinists must test themselves. Now seems the appropriate moment. For one, she is no longer quite the innocent abroad who gave such a delicate interpretation of the Mendelssohn. “It sounds quite polite and careful in comparison to how I’ve been performing it since,” she says. “But there are lots of things that are a little bit vulnerable about the recording which I think really suit the youth of the piece.”

Those qualities would not work for these two concertos. Both were composed by young (or youngish) men, at an equivalent moment in still nascent careers. Bruch was 28 in 1866 when he completed his first violin concerto, Op 26 in G minor, although it was then reconfigured and re-premiered a year later. Tchaikovsky was 10 years older in 1878 when the D major concerto, Op 35, was written, but at a point when he was only beginning to find fame.

There is a historical link too. Tchaikovsky worked up his concerto while staying on Lake Geneva in Switzerland. He was joined by a composition student of his who happened also to be a violinist. Yosif Kotek arrived from Berlin, where he had been working with his violin teacher Joseph Joachim. It was Joachim who, 11 years earlier, had first performed the revised version of Bruch’s concerto.

There is a certain straightforwardness about the Bruch that suits me

But they should not be seen as cut from the same cloth, says Benedetti. They are musical expressions of two wholly different psychologies. “They are two unique concertos. The only similarity is a romantic, passionate soft-heartedness. Bruch”, she explains, “always has a certain content in his music. There is something that is peaceful. The passion is quite youthful. Even the second movement, which is heartrending and one of the best Romances ever written, is still so joyous. The softer moments have this kind of calm. The most euphoric and dramatic moments are searching but always end in this blissfulness. There was definite happiness there somewhere and he could find it quite easily. His character and his feelings were perfect for a violin concerto.”

Not that the composition was without experimental flourishes. Bruch’s was the first major violin concerto to adopt the Mendelssohnian technique of segueing between movements – the first movement is conjoined to the Romance by a low note from the first violins – and dispensing with an excess of orchestral framing. “There are very few concertos with that sort of structure,” she says.

Not that the composition was without experimental flourishes. Bruch’s was the first major violin concerto to adopt the Mendelssohnian technique of segueing between movements – the first movement is conjoined to the Romance by a low note from the first violins – and dispensing with an excess of orchestral framing. “There are very few concertos with that sort of structure,” she says.

The emotional landscape conjured up by Bruch, still young, freshly celebrated and not yet exposed to the disappointments which life would later inflict, is thus benign. The Romance swoons, but there is resolution. Agony is vanquished by ecstasy. “There is a certain straightforwardness about the music that suits me,” Nicola says. “It doesn’t have a million and one levels. Pretty much what you hear is what you get. I tend to have an unaffected and natural approach to playing things so I think the simplicity and flow of Bruch’s music probably suits that side of me.”

Compare and contrast with Tchaikovsky. “It tends to be a trend for composers who have reached higher than all their peers that, generally speaking, they haven’t lived such happy, comfortable existences. With the real Romantics like Tchaikovsky, it is an outpouring of something that’s going on inside. You try to think of one moment of contentment in Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto. You can’t find it anywhere, even when it’s a beautiful melody that’s really meant to be something that depicts love or passion. It’s still so filled with this unrest. There’s just so much turmoil, so much questioning.

“The second subject of the first movement, for instance, which begins so contained, develops into something so obsessive and unrelenting to the point where the violin is literally crying out for something that can’t be satisfied. It’s like nothing can be enough. That is the biggest contrast in the two pieces.”

The unrest, it is often presumed, is the composer’s furious response to the bitter catastrophe of his marriage to Antonina Miliukova (pictured with Tchaikovsky, left). The violin concerto was one of the compositions in which Tchaikovsky’s struggle with his homosexuality seemed to surface most potently in his music. It’s intriguing to speculate whether, even if only at a subconscious level, this was at the root of the concerto’s initially cool reception. Its structural anxiety, its obsessive repetitions and failure to seek out resolution may have come across as not just artistically unseemly, but morally so too.

The unrest, it is often presumed, is the composer’s furious response to the bitter catastrophe of his marriage to Antonina Miliukova (pictured with Tchaikovsky, left). The violin concerto was one of the compositions in which Tchaikovsky’s struggle with his homosexuality seemed to surface most potently in his music. It’s intriguing to speculate whether, even if only at a subconscious level, this was at the root of the concerto’s initially cool reception. Its structural anxiety, its obsessive repetitions and failure to seek out resolution may have come across as not just artistically unseemly, but morally so too.

The first soloist to find fault with it was its dedicatee, Leopold Auer. The distinguished soloist counted the honour conferred by Tchaikovsky a mixed blessing. “My first feeling was one of gratitude for this proof of his sympathy toward me”, he said many years later, “which honoured me as an artist. On closer acquaintance with the composition, I regretted that the great composer had not shown it to me before committing it to print. Much unpleasantness might then have been spared us both.”

Auer denied, as had been reported, that he had declared the concerto “unplayable”. But he did think it suitable to make adjustments, particularly to the conclusion. “He didn’t necessarily make the third movement so much easier,” says Benedetti. “He just made it a bit less tiring. In my opinion the third movement was just massacred by Auer. The whole concerto had this crazed, repetitive and extremely wild rustic character, and to cut out every single repetition was a completely crazy thing to do. And a lot of the small technical things he added just slightly cheapened the wild drive of the concerto.”

The changes were partly a question of technical correction. Benedetti allows that Tchaikovsky “never wrote particularly well for the violin”, by which she means his knowledge of what was feasible on the instrument were limited. “It’s not terribly violinistic, in that it’s really quite awkward, quite uncomfortable. He doesn’t use techniques really developed by Paganini and Sarasate.” But that, she adds, is the piece’s strength. It doesn’t trouble itself with the tricksy harmonics and exploratory fripperies. In short, Tchaikovsky took out his frustration on the violinists of posterity, from Auer onwards.

This summer concert-goers in the Borders had a live preview of her next recording when she performed a series of Italian Baroque concertos by Vivaldi and Tartini. And one day she’d like to have another crack at Mendelssohn, preferably live in front of an audience. “You know you’ve got just the one chance. You give everything you can in that half an hour. Once you start you’re there till the end. And there’s no going back.”

- Find Nicola Benedetti on Amazon

Nicola Benedetti plays Mendelssohn:

Add comment