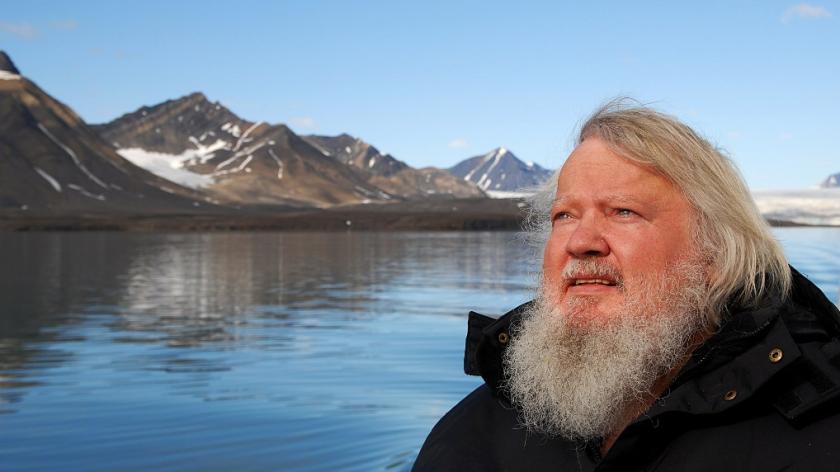

The BBC Radio 3 announcer came on stage to introduce the concert and promised us "the 100 minutes" of Bruckner’s Eighth Symphony in the second half. Some of us smiled and assumed he (or his scriptwriter) had made a howler. Last time the Eighth was done in London, Jukka-Pekka Saraste led a vigorous account, not unduly rushed, taking under 75 minutes. The announcer, did we but know it, was giving us fair warning. Three hours later, boos and cheers mingled as the Brahmsian figure of Leif Segerstam shuffled off stage, wreathed in unBrahmsian smiles. London audiences boo at horrid German purveyors of operatic Regietheater. They do not boo at Bruckner.

The symphony’s performance was all the more unsettling after the first half’s sequence of motets. If this had been designed to place the symphony in context and illustrate Bruckner’s heritage as a musician and composer in archaic polyphony, the concept was stumped from the outset by an acoustic without the resonance built in to the fabric of Bruckner’s motets in particular. Attempts to reduce vibrato and keep the articulation light and crisp served Bach’s Jesu meine Freude better, but even reduced to 18 voices and directed with sober good sense by James O’Donnell, the BBC Singers make a defiantly old-fashioned sound in this repertoire.

After the interval there were 18 first violins alone, and the proportions of the BBC Symphony orchestra were inflated likewise to Straussian size, fit for hurling themselves up the Alpine Symphony, ready to fulfil the Eighth Symphony’s superfluous old nickname of "The Apocalyptic". This is the kind of Bruckner orchestras hate to play – they can’t listen to each other because they can hardly hear themselves think, let alone play – and there were some thunderous looks on stage, as if shot from members of a family whose long-lost and hard-of-hearing great-uncle has come to stay, thrown out the TV and is regaling them with tales from his life story.

Relative speed met with volume like a lorry meets with a concrete wallHuge climaxes offered no resolution because it took a conscious act of memory to recall whatever it was they were supposed to be resolving. They rumbled on like thunder, but there had been no lightning, or lightening, and no uneasy calm before the storm, no calm or stillness anywhere because the volume was turned up throughout: every dynamic marking was at least one notch higher than is marked, or appropriate.

But then "appropriate" is not a word in Segerstam’s Bruckner-lexicon. To get technical for a moment, the Trio of the Scherzo has two crotchets to every bar. To behave like a trio, it needs to move in three beats: one beat for every bar. Segerstam conducted in quavers, four to a bar: so a quarter as fast as the score implies. The other movements started out at a slow but plausible tempo, then slowed to a crawl for their second and third themes, and largely stayed there. Only the outer sections of the Scherzo went at anything like normal tempo, and these made least sense of all, because relative speed met with volume like a lorry meets with a concrete wall.

If you could breathe more slowly and stop groping for a pulse, if you could forget the stories the symphony usually tells, of C minor transformed only at the last into a brilliant C major, of a death-watch dotted rhythm that holds it together, there were passages of wintry beauty, especially in the Adagio whose first theme was hardly underpinned by the Wagnerian throbbing of Stephen Johnson’s account in his programme note, spaced more like waystones across Egdon Heath. That so much made a weird sense of its own, much credit must go to the BBCSO, who have a fine Bruckner-tradition of their own stretching back to Günter Wand and Rudolf Kempe, but who will rarely have been asked to step so far outside a comfort-zone of familiarity. The brass played till they were fit to burst but (almost) never made an ugly chord. The first oboe (Richard Simpson) cut through swathes of string sound with a penetrating, otherworldly beam, quite unlike his usual voice. Julie Price’s bassoon was another highlight, even in the opening solo allotted to her by Segerstam (Bruckner scored it for clarinet).

Star-ratings were not made for such evenings. Certainly not for Segerstam. When he returns to London, I’ll be there, if only to see what happens next.

- The concert is available here on the BBC iPlayer until 28 March.

Add comment