Sir Charles Mackerras: The Complete Warner Classics Edition (Warner)

That Sir Charles Mackerras’s long recording career included releases on a slew of different labels means it’s unlikely that a complete box set will ever be compiled. Here’s the next best thing, Warner Classics’ hefty 63-disc set collecting the material Mackerras taped for EMI, Pye and Virgin Classics. Mackerras’s versatility is clear from the track listing; there’s an unfeasibly wide range of material here. Take a look at the ‘B’ section in the booklet – what other conductor could turn in persuasive performances of music by composers as diverse as Bartók, Berlioz and Havergal Brian? The earliest item here is a 1951 Sadler’s Wells Orchestra disc of Mackerras’s Pineapple Poll, an infectiously jolly one-act ballet based on music from Gilbert and Sullivan operettas. The 1960 stereo remake is included, as is a 1977 performance of the ballet suite. Sullivan’s music was a Mackerras speciality, and EMI allowed him to tape his reconstruction of the composer’s Cello Concerto in the 1980s with Julian Lloyd-Webber. It’s no masterpiece, but fun to hear. More interesting is The Lady and the Fool, a ballet based on material from rarely heard Verdi operas. Mackerras’s 1955 recording is included, superbly played by the Philharmonia in vivid early stereo.

Two discs made for the budget Pye label are essential listening, the earliest (1958) coupling Janácek‘s Sinfonietta with four opera preludes. London’s pick-up Pro Arte Orchestra play with a blazing intensity that transcends the slightly dim sound. A year later, Mackerras recorded a pioneering account of Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks using the same number of players who’d taken part in the 18th century premiere – think 26 oboes, 14 bassoons and legions of brass. In the conductor’s words, “in order to assemble the extraordinary orchestra… we had to record it in the middle of the night, when no other orchestras were working. The session finished at 2.30am on the 200th anniversary of Handel’s death… it was one of the most marvellous noises I have ever heard in my life, and most moving.” This is still my go-to version of the work on modern instruments, Mackerras’s 1976 remake with the London Symphony Orchestra more vividly recorded but not as exciting. There’s an idiosyncratic but enjoyable version of Handel’s Messiah, made with a smaller chorus than was the norm in 1966, and stylish accounts of the Op.3 Concerti Grossi and Water Music made with the Prague Chamber Orchestra.

Mackerras will be remembered as a Czech music specialist, having studied in Prague with Václav Talich immediately after World War 2. His later Janácek recordings were made for Decca and Supraphon, but this set does include idiomatic readings of Dvorák’s last three symphonies and Symphonic Variations with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, Mackerras really letting the winds and brass sing. Other recordings of mainstream repertoire here include an excellent, historically informed Beethoven cycle with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra plus Mahler’s 1st and 5th symphonies. These were originally released on EMI’s budget Eminence label but you’d happily pay top whack for performances this good. The RLPO are featured in several other of Mackerras’s later digital recordings, with excellent versions of Holst’s Planets, the Mussorgsky/Ravel Pictures at an Exhibition and, a particular favourite of mine, Rachmaninov’s Symphony No. 3 and Symphonic Dances. There’s also an intriguing Delius anthology and a disc containing two Havergal Brian symphonies.

Mozart, Schubert and Mendelssohn all feature. Mozart’s Idomeneo is heard with the traditional cuts restored and Mackerras’s Mendelssohn and Schubert symphonies, taped with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, are full of energy. And where else will you find a pulverising account of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring sharing box space with the likes of Favourite Music of Eric Coates and The Elizabeth Schwarzkopf Christmas Album? Or highlights from Wagner’s Götterdämmerung alongside frothy overtures by Wolf-Ferrari? It’s that sort of a package, and I’ve not mentioned the various collections of folk songs, opera entr’actes and ballet excerpts. Open the box, pick a disc at random and you’ll invariably find something to intrigue, delight and entertain.

Bartók: The Miraculous Mandarin & Concerto for Orchestra Toronto Symphony Orchestra/Gustavo Gimeno (Harmonia Mundi)

These two Bartók pieces are both well-represented in the catalogue, and often paired together. The Bartók ballet is often heard in its suite form, although you really need the full thing (with choir) to get the full effect. My go-to recording has always been Simon Rattle and the CBSO from the early 90s, and I also like Iván Fischer with the Budapest Festival Orchestra (on separate releases). But this new recording by the Toronto Symphony Orchestra has lots going for it, including the novelty of the premiere of Emilie Cecilia LeBel’s the sediments, sandwiched between the two Bartók masterpieces.

LeBel’s nine-minute work, orchestrated with glistening colours and weighty, unfolding form, is inspired by the writing of environmentalist Rachel Carson. As the composer says in her liner note: “I think about the weight of sediment, and our history. Water flows on whether I am here or not” and there is a corresponding ineluctability about the progression of the music. It’s beautifully played, with the orchestral layers always carefully balanced, and a captivating listen, even if it doesn’t seem to have much to do with the pieces that surround it. But still it holds its own in illustrious company.

The Miraculous Mandarin, a one-act ballet finally completed by Bartók in 1924, is as colourful an orchestral score as you could want. It caused a scandal at its premiere in Cologne in 1926, as much for its confrontational music as its violent and dramatic story. The Toronto players go at it with a purpose, from the fizzing opening moments, but also find an eerie, unsettling mood in the “Dance of the Girl”. The offstage chorus in the finale (the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir) has a suitable weirdness, and the final passage of chuntering bass clarinet and insistent low brass is nicely done.

The Concerto for Orchestra is cut from very different cloth, its exuberance and sunny demeanour belying the fact that Bartók was dying while composing it. It is an upbeat piece on the whole, with the brass shining in its big climaxes, and the winds finding the wit in the “Game of Pairs” and the “Interrupted Intermezzo”. But at the heart of the piece, the central “Elegy”, the orchestra finds a bleached aural landscape that is closer to the chilly world of the Mandarin. Bernard Hughes

Nielsen: Symphonies 1-6, Overtures & Concertos Danish National Symphony Orchestra/Herbert Blomstedt (Warner Classics)

New Carl Nielsen recordings have been thin on the ground in recent years, with symphony cycles from Alan Gilbert, Sakari Oramo and John Storgards all released over a decade ago. So, this reissue deserves attention by default, even though these analogue recordings have been intermittently available on disc since the 1990s. They date from a collaboration between EMI and Danish Radio, issued to celebrate the composer’s 110th anniversary in 1975. The Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra were credited on the original box set; Warner Classics, a little confusingly, give the ensemble its current title. The original records always sounded decent, certainly easier on the ear than Ole Schmidt’s contemporaneous London Symphony Orchestra cycle, rough-edged but still exciting. Warner have given EMI’s master tapes a high-definition makeover, the eight LPs now squeezed onto five SACDs.

Tempi in the early symphonies are generally more expansive than in Blomstedt’s 1980s San Francisco remakes for Decca. This isn’t necessarily a problem; I like Blomstedt’s big-hearted take on Nielsen’s delightful Symphony No 1, a work nominally in G minor that opens with a C major chord. There’s no lack of fire in the choleric first movement of Symphony No. 2 (try the orchestral snarl a minute before the movement’s close), and the “Andante malincolo” is moving. I prefer this Symphony No. 3 to the later performance, the analogue sound warmer, Blomstedt’s hard-working players (he was this orchestra’s Principal Conductor from 1967 to 1977) giving their all. Blomstedt’s tempo in the anthemic finale is ideal, and listening to it is like spending nine minutes under a sun lamp. A pity that Warner omitted the names of the two vocalists in the slow movement (soprano Kirsten Schulz and tenor Peter Rasmussen).

Symphonies 4 and 5 are exciting if occasionally untidy, with a viscerally exciting timpani duel in the former’s closing minutes. No. 5 starts well, but the side drum solo lacks menace and the Danish brass are audibly flagging near the close of the first movement. The second half fares much better, Blomstedt whipping up plenty of adrenalin in the final minutes. Nielsen’s enigmatic 6th Symphony is superbly done, with a (literally) heartbreaking climax in the “Tempo giusto” and an eerie “Proposta seria”. And listen to the finale’s coda, strings dancing ever higher before a farting bassoon wraps things up.

Disc 4 contains a selection of Nielsen’s shorter orchestral pieces, all well done. Blomstedt’s Pan and Syrinx is exciting, and there’s some expressive string playing in the Andante lamentoso. Disc 5 contains the three concertante works. I’m fond of the sprawling Violin Concerto, a work which can sound as if the sections have been shuffled and performed in the wrong order. Not here: Arve Tellefsen is commanding in the imposing “Praeludium” and nicely relaxed in the 3/8 finale. Kjell-Inge Stevensson nails the Clarinet Concerto’s strangeness and there’s an engaging performance of the compact Flute Concerto from Frantz Lemmser with an excellent bass trombone in the final minutes. I’d have liked some information in the booklet about the early 1970s recording sessions and on Blomstedt’s relationship with this composer, but this re-release, in handsome sound, still serves as a useful introduction to a great 20th century composer.

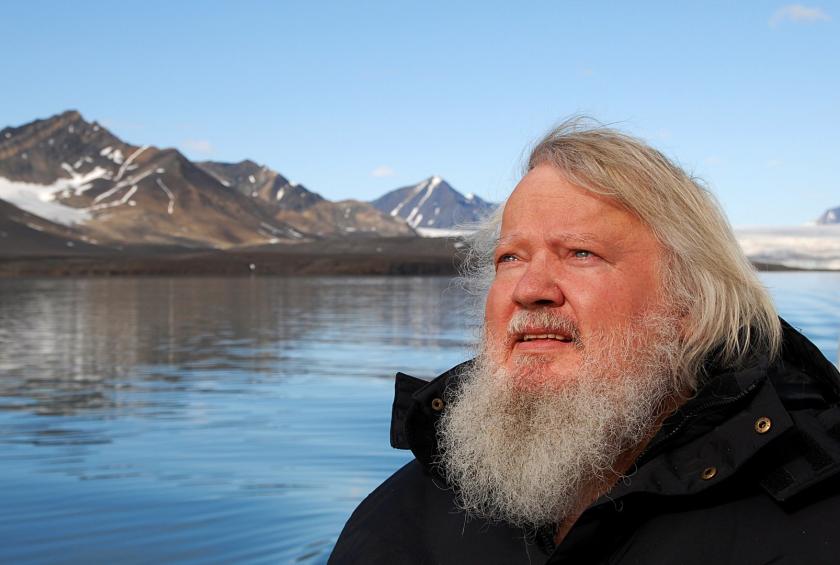

Leif Segerstam: The Complete Sibelius Recordings Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra/Leif Segerstam (Ondine)

Coming from Finland doesn’t automatically mean that you’ll be an excellent Sibelius conductor, but several of the best Sibelius cycles on disc are Finnish – think Osmo Vänskä, Jukka-Pekka Saraste, Okko Kamu and Paavo Berglund (who recorded the symphonies three times). Plus Leif Segerstam (1944-2024), whose second swathe of Sibelius recordings with the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra forms the centrepiece of this 15-disc set. The booklet contains some useful biographical info; Segerstam beginning his career in the early 60s as an opera specialist before making the sideways move to purely orchestral conducting, and declaring himself ‘Generalmusikdirektor of the North” in the 1990s while holding three posts in Scandinavian cities. There’s also his compositional career, Segerstam’s output including 371 symphonies. Do look at the Wikipedia page which lists basic details of each symphony, works with names like More Serious than Sexy, Tsunamic Zoomings and Flashbacking Backwardsly.

The performances here span the years 1994 to 2007, highlights including terrific performances of the two Tempest suites and a uniquely chilly Tapiola, the latter sharing disc space with a cogent, colourful account of the four Lemminkäinen Legends, a symphony in all but name. Sibelius’s early epic Kullervo is another standout, blessed with some magnificent choral singing and good soloists. A pair of early secular cantatas are fun to hear, neither one sounding much like the mature composer but showcasing his knack for churning out effective occasional pieces. We do get two well-filled discs of orchestral songs, magnificently sung by baritone Jorma Hynninen and soprano Soile Isokoski, whose Luonnotar is a stunner. I struggled with Sibelius’s Violin Concerto for years until hearing the version in this box, soloist Pekka Kuusisto incredibly persuasive and brilliantly accompanied.

The seven symphonies fill the first four discs in very good, occasionally great, performances. Segerstam mines the drama and revels in the warmth of Nos. 1 and 2, highlighting their debt to Tchaikovsky, and directs a clean, propulsive account of No. 3. This 4th is superb, the Helsinki lower strings pitch black in Sibelius’s grinding opening, the slow movement’s huge eruption a seismic moment. 5 is decent without being especially distinctive, whilst the 6th and 7th are wonderful, superbly paced and beautifully coloured. As modern Sibelius cycles go, Segerstam’s is a keeper, Ondine’s sound rich and detailed.

Four entertaining bonus CDs are thrown in. I’d not encountered Sibelius’s short-lived pupil Toivo Kuula before hearing Segerstam’s album of his orchestral works. A pair of South Ostrobothnian Suites contain some charming music, “Rain in the Forest” conjuring a downpour with swirling strings and a soft drum roll, “The Will-o’-the-Wisp” a fully-developed tone poem. CD 13 features Erkki Melartin, a Sibelius contemporary who spent his career in the older composer’s shadow. His Suite Lyrique No. 3 is subtitled “Impressions de Belgique” and it’s a delight, Melartin’s evocations of nocturnal Bruges and pealing church bells wonderfully realised here. CD 14 is titled Pictures from Finland, its twelve tracks including an ebullient concert overture by Uuno Klami and Selim Palmgren’s evocative sleigh ride. I keep returning to the tiny Praeludium by Armas Järnefelt, lasting a little less than three minutes and completely irresistible. And, finally, there’s Scandinavian Rhapsody, another frothy anthology. Lumbye’s Champagne Galop is great fun, and the Helsinki strings dazzle in Alfvén’s little Dance of the Shepherd Girl. Segerstam’s version of Grieg's In the Hall of the Mountain King is electrifying and he injects similar levels of oomph into Nielsen’s Maskarade Overture. A genuinely great box set: get it while you can.

ContraDANCE MZ Duo (Delphian)

MZ Duo are saxophonist David Zucchi and accordionist Iñigo Mikeleiz-Berrade, whose debut album ContraDANCE explores the possibilities of these two 19th century inventions. Both instruments have found their most successful niches outside classical music – in klezmer, tango and zydeco for the accordion, and jazz and pop for the saxophone – but here the focus is on arrangements and new commissions from within the classical world.

The two new pieces are both successful, albeit in very different ways. The album opener The Mirrie Dancers, by Aileen Sweeney (b.1994) is an initially dreamy and free-flowing evocation of the Northern Lights as seen from the Shetland Islands, with the musical material indebted to the folk music of the region. The energy builds to a hallingdansen, a whirling Norwegian dance, before receding again, Zucchi’s singing line in the low soprano register sings eloquently.

The other piece is by Alex Paxton, whose hyperactive, saturated music I have enjoyed since I first heard it. The other pieces of his I have heard have had a wider timbral palette, but Water Butt: lovers, snorkel makes the most of the two instruments – augmented by both players vocalising. It generates its restless energy through rhythmic invention coupled with Paxton’s usual freewheeling melodic whimsy and improvisatory curlicues. There is always a joyfulness in Paxton’s music, and the players here respond in kind, with Mikeleiz-Berrade conjuring all sorts of squeaks and shouts from his accordion.

The other items are tamer – but well-chosen. Granados’s Danzas Españolas established him as a leading voice in Spanish music in the 1890s. Originally piano pieces, they transpose well to the duo, the echoes of Spanish folk music clearly audible, coupled with a kind of pre-neoclassical grace. There is a similar folk element to Bartók’s brilliant Dance Suite, originally for orchestra, then piano – and now in this new duo arrangement. Like the Granados, it evokes rather than quotes folk styles – not just Bartók’s familiar eastern Europe, but north Africa and Arabia. They are played with a wonderful extrovert energy, and the piquant harmony fits the accordion perfectly.

The only less successful item is the four-movement version of Ravel’s Le Tombeau de Couperin. This works well for wind instruments (see my review of Ensemble Ouranos in the last column) but for me doesn’t quite work in this combination. It was the one time in the album where I regretted the narrow timbral range, in which Ravel’s sensibility doesn’t seem to belong, and missed the skittering overlapping lines of the original versions – and indeed of the wind quintet. But this is the only misfire on an excellent first release. Bernard Hughes

Add comment