Pre-Raphaelites, eat your heart out; and wherever he is, John Ruskin, once so dismissive of the artist, must be beaming with pleasure. The American landscape painter Frederic Church (1826-1900) was indeed seen as the heir to Turner, and his distinct landscape idiom is encapsulated by a handful of oil sketches – just over two dozen – of scenes from the Hudson River Valley to Petra, Ecuador to Newfoundland, Bavaria to Salzburg, Jamaica to Labrador.

It is enough to give a tantalising glimpse of his extraordinary fluency with colour, texture and composition, at the service of a passionate response to landscape. He sought the spiritual in art, sometimes a little portentously. His much larger and smoothly finished showpieces (not on show here) made him one of the most wildly successful painters of his period, but 21st-century taste undoubtedly prefers the glittering intensity of these sparkling sketches.

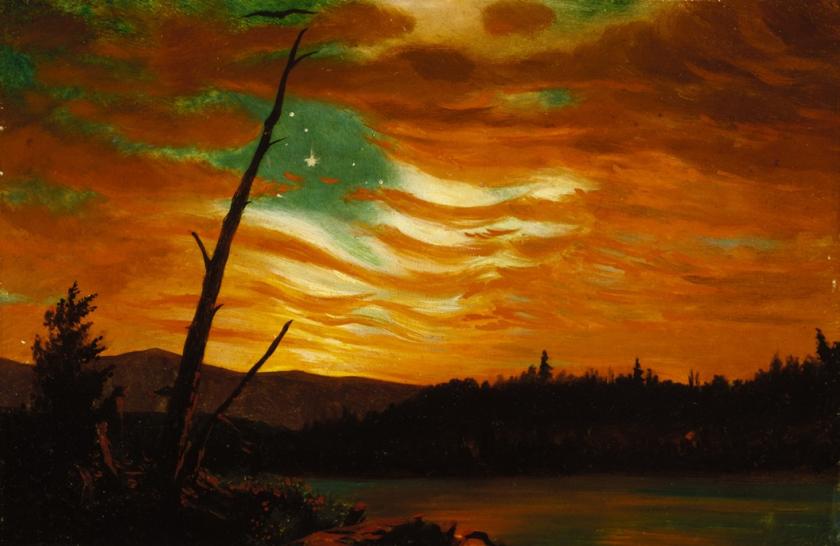

“Of all employments I find this the most delightful,” he remarked of sketching in oil out of doors, and he produced hundreds. The controlled exuberance and enthusiastic tenacity with which natural features are portrayed in these closely-observed scenes are almost hypnotic in their effect. Scudding clouds, glowing sunsets, rippling water, icebergs radiating light, a fiery volcano and the rising sun are amongst his subjects. In small compass, vistas can be as grand as floating icebergs, the blue mountains of Jamaica and the Bavarian Alps, or as humble as a campfire in the Maine woods.

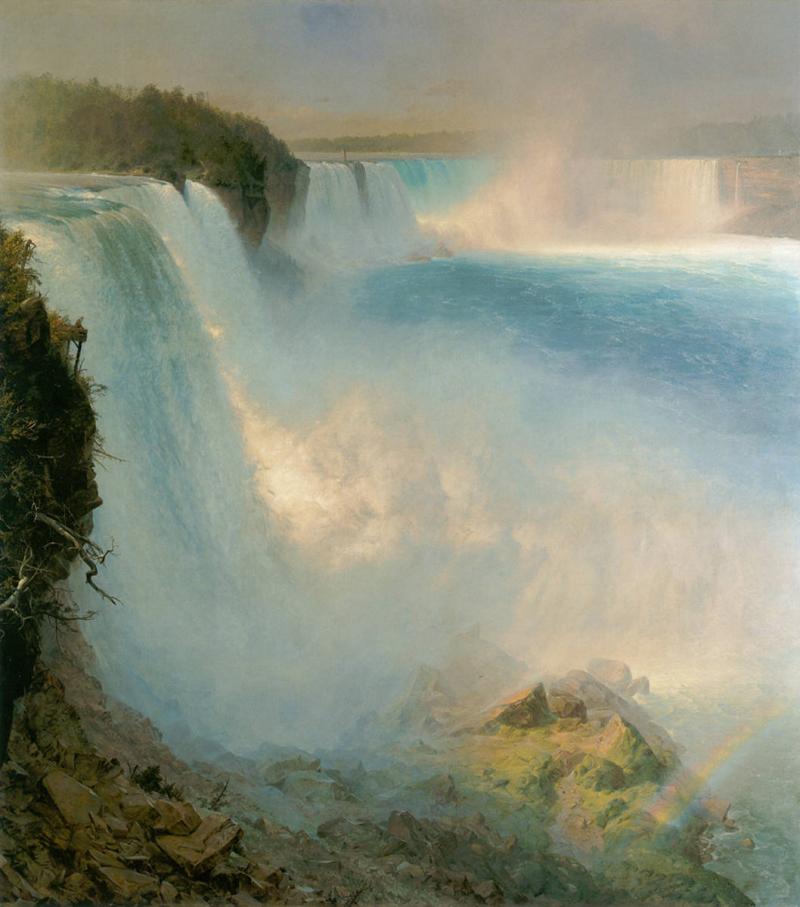

Church indeed paid conscious homage to the ideas of John Ruskin. He visited England and studied Turner at the National Gallery, but his only major painting in the UK, the large scale Niagara Falls, from the American Side, 1867 (pictured right), is in the National Gallery of Scotland. It has made its way from Edinburgh to London for this show, and is complemented by four vivid oil sketches of the subject. Looking at these torrents of water casting off glittering rainbows, and roaring past brilliantly delineated rock cliffs, you can practically hear the staggering noise of the cascades, and feel the spray.

Church indeed paid conscious homage to the ideas of John Ruskin. He visited England and studied Turner at the National Gallery, but his only major painting in the UK, the large scale Niagara Falls, from the American Side, 1867 (pictured right), is in the National Gallery of Scotland. It has made its way from Edinburgh to London for this show, and is complemented by four vivid oil sketches of the subject. Looking at these torrents of water casting off glittering rainbows, and roaring past brilliantly delineated rock cliffs, you can practically hear the staggering noise of the cascades, and feel the spray.

As someone who has visited more than half of the sites Church depicts, it’s possible to testify that, as a realist landscape painter with a mesmerising attention to detail, he uncannily captures the feeling of these vast landscapes with more than a hint of the sublime, as well as relatively modest subjects such as The Forest Pool. Here you can almost sense the variegated degrees of softness and hardness when you walk on the mulch of the forest floor, and the glinting light that flickers on the plants that form the woodland carpet.

Graceful ferns, in a multiplicity of tones of greens and browns, are a concatenation of curves choreographed by an unseen wind in Fern Walk, Jamaica. This entrancing sketch was painted during a turbulent time, when Church and his wife were recovering from the sudden death of their young son and daughter from diphtheria; whilst Isabel Church was collecting ferns for their great garden surrounding their purpose built mansion, Olana, on the bank of the Hudson, the artist immortalised the scene. It was framed and kept in their home, where it still hangs.

Church was famous in London in the 19th century but British holdings of 19th-century American art are negligible and American art of the period is rarely sighted here. This small, perfectly formed show in Gallery 1 of the National continues their recent exploration of the subject, and complements their own European landscape oil sketches on view across the lobby in Gallery 46.

Add comment