Colours had meanings for Emil Nolde. “Yellow can depict happiness and also pain. Red can mean fire, blood or roses; blue can mean silver, the sky or a storm.” As the son of a German-Frisian father and a Schleswig-Dane mother, Nolde was raised in a pious household on the windswept flat land on the border on Germany and Denmark that his family farmed. The Bible was practically the only book in the household and had been in the family for nine generations, and his understanding of colour was drawn as if from a chromatic psalter.

The exhibition is divided into five rooms, more thematic than chronological – and each one glows. In the first, a series of faces and one subtle grey cityscape, Canal, (Copenhagan), 1902, greet the visitor. The room just pops with colour. The yellow limned Self-portrait, 1917 glances over with sky blue visionary eyes, and in Farmers’ Sons, 1915 two brothers stare directly out of their portrait, gazes level, bright ties carefully tucked in sombre suits and high collars – boxed in by formality but noticeably individual young boys. Another self-portrait, this time symbolic rather than pictorial hangs in the same room. In a letter to a friend, Nolde identified himself with the figure in orange in Free Spirit, 1906 which resonates compositionally with traditional imagery of Christ before his crucifixion. While those around him gesture and censure, the orange clad figure of the artist stands still, hands carefully in repose, keeping his conviction among a storm of opinion.

The exhibition is divided into five rooms, more thematic than chronological – and each one glows. In the first, a series of faces and one subtle grey cityscape, Canal, (Copenhagan), 1902, greet the visitor. The room just pops with colour. The yellow limned Self-portrait, 1917 glances over with sky blue visionary eyes, and in Farmers’ Sons, 1915 two brothers stare directly out of their portrait, gazes level, bright ties carefully tucked in sombre suits and high collars – boxed in by formality but noticeably individual young boys. Another self-portrait, this time symbolic rather than pictorial hangs in the same room. In a letter to a friend, Nolde identified himself with the figure in orange in Free Spirit, 1906 which resonates compositionally with traditional imagery of Christ before his crucifixion. While those around him gesture and censure, the orange clad figure of the artist stands still, hands carefully in repose, keeping his conviction among a storm of opinion.

The NGI’s dark walls and low lighting allow for a measure of privacy between viewer and artist and set off his pigments with an intensity akin to how he must have perceived his subjects. This perceptual acuteness is maintained throughout the rooms and between works which range in size from the triptych Martyrdom I, II, III, 1921 which takes up an entire wall, to constellations of pen and ink drawings of boats in Hamburg’s busy harbour. His facility with different materials is also on show, with displays of oils, woodcuts, watercolours, etchings, and lithographs. All but two of the pieces on display are from the Nolde Foundation in Seebüll, and the frames are either originals or made in his customary style (kohl-dark, wide) which set off their colours. As the works on paper are so fragile and the Dublin leg relatively long, on 14th May other works will be swapped in, effectively making two exhibitions. In Scotland all the works will be displayed together.

The NGI’s dark walls and low lighting allow for a measure of privacy between viewer and artist and set off his pigments with an intensity akin to how he must have perceived his subjects. This perceptual acuteness is maintained throughout the rooms and between works which range in size from the triptych Martyrdom I, II, III, 1921 which takes up an entire wall, to constellations of pen and ink drawings of boats in Hamburg’s busy harbour. His facility with different materials is also on show, with displays of oils, woodcuts, watercolours, etchings, and lithographs. All but two of the pieces on display are from the Nolde Foundation in Seebüll, and the frames are either originals or made in his customary style (kohl-dark, wide) which set off their colours. As the works on paper are so fragile and the Dublin leg relatively long, on 14th May other works will be swapped in, effectively making two exhibitions. In Scotland all the works will be displayed together.

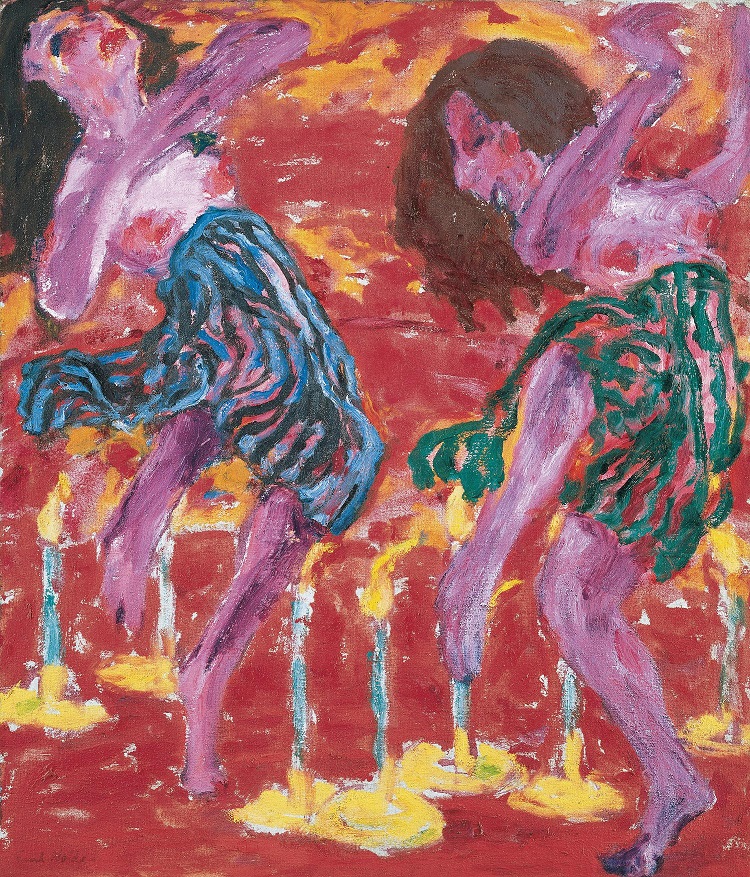

In later rooms concerned with his trip to the South Sea Islands and his frequent visits to the cabarets in Berlin, movement also emerges as a stimulus and inspiration. In Candle Dancers, 1912 (pictured above, right) skirts like green ribbons tumble from two dancers’ bare torsos, and a sense of uninhibited freedom conjoins the flames among which they dance with their wild limbs. Equally elemental are a series of spell-binding watercolours of Chinese junks Junk (in Full Sail), 1913, and Junks (Red), 1913 (main picture) in which each vessel is animated by wind that tilts them towards their destinations, the entire purpose of their existence being to traverse seas. A watercolour made around the same time, Aboriginal Man Swimming, 1914 (pictured above, central) revels in the glorious play of limbs and waves, the free brushstrokes expressing the joy of buoyancy in loose swathes of colour. It’s as if in movement that Nolde finds a force that gives life to the meaning he sees though colour.

Notwithstanding, Nolde also left a troubling legacy. He was a member of the Nazi party and found favour with Goebbels before being branded a “degenerate artist”, a label which salvaged his reputation after the end of World War Two. Heated debate rages around the extent and duration of his commitment to the party and their aims, and while essays included in the catalogue deal extensively with this side of his biography, the exhibition itself foregrounds this part of his life through the wet-on-wet watercolours he painted while banned from practising as an artist. These “Unpainted Paintings” (such as Skater, no year attributed pictured above left) depict an interior life of dazzling landscapes where skaters hurtle off the page, dinosaurs survey horizons, fire spirits cavort, and goblins prance. The colours shimmer and the lines are sinuous and assured. Each is a glimpse of manual dexterity combined with an interior life riven with myth and imagination. Taken together, they pose the question of how far works and biography can or should be separated with extreme pertinence, and the careful curation keeps the question live.

Notwithstanding, Nolde also left a troubling legacy. He was a member of the Nazi party and found favour with Goebbels before being branded a “degenerate artist”, a label which salvaged his reputation after the end of World War Two. Heated debate rages around the extent and duration of his commitment to the party and their aims, and while essays included in the catalogue deal extensively with this side of his biography, the exhibition itself foregrounds this part of his life through the wet-on-wet watercolours he painted while banned from practising as an artist. These “Unpainted Paintings” (such as Skater, no year attributed pictured above left) depict an interior life of dazzling landscapes where skaters hurtle off the page, dinosaurs survey horizons, fire spirits cavort, and goblins prance. The colours shimmer and the lines are sinuous and assured. Each is a glimpse of manual dexterity combined with an interior life riven with myth and imagination. Taken together, they pose the question of how far works and biography can or should be separated with extreme pertinence, and the careful curation keeps the question live.

Nolde was an influential German Expressionist, a Nazi supporter, a “degenerate artist”, and a brilliant colourist. All these things are important, and this exhibition rightly makes all these things known.

- Emil Nolde: Colour Is Life at National Gallery of Ireland to 10 June, then at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art 14 July-21 October

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment