Cornelia Parker, Tate Britain review – divine intelligence | reviews, news & interviews

Cornelia Parker, Tate Britain review – divine intelligence

Cornelia Parker, Tate Britain review – divine intelligence

The most interesting artist of our time

Cornelia Parker’s early installations are as fresh and as thought provoking as when they were made. Her Tate Britain retrospective opens with Thirty Pieces of Silver (pictured below left: Detail).

Since Parker is a conceptual artist as much as a sculptor, there’s a back story to the work and knowing it enriches one’s experience of the piece, since it lets you in on her thought processes. As a child, she received annual gifts of silverware from her German grandparents; odd presents for a girl, suggesting a desire to secure her future by contributing to her bottom drawer.

At the time of making the work, the squat where she lived in Leytonstone was about to be demolished to make way for a slip road to the M11. She began augmenting her own collection with candlesticks, cutlery, teapots, jugs and sugar bowls bought in car boot sales and at auction. Squashing these emblems of security and wellbeing was partly a reflection of the imminent dislocation and partly an act of defiance, proof that destruction could be harnessed to become a creative force.

The title refers to the reward that, according to the Bible, Judas received for betraying Christ. For the artist, corruption, wickedness and violence are a foil, sparking ideas and fostering creativity. And her funny, ironic and generous responses come as a positive alternative to the negative impulses which provoke them. Stolen Thunder, Tarnish 1997/8, for example, consists of pristine white cloths stained with smudgy grey marks produced by polishing silverware that belonged to famous villains or heroes. The idea of creating drawings by cleaning Guy Fawkes’s lantern, Davey Crockett’s fork or Henry VIII’s armour is obviously absurd. There’s a mixture of deference and irony in the act which, along with the frisson of borrowed fame or ignominy, invites us with wry humour to question our values.

The title refers to the reward that, according to the Bible, Judas received for betraying Christ. For the artist, corruption, wickedness and violence are a foil, sparking ideas and fostering creativity. And her funny, ironic and generous responses come as a positive alternative to the negative impulses which provoke them. Stolen Thunder, Tarnish 1997/8, for example, consists of pristine white cloths stained with smudgy grey marks produced by polishing silverware that belonged to famous villains or heroes. The idea of creating drawings by cleaning Guy Fawkes’s lantern, Davey Crockett’s fork or Henry VIII’s armour is obviously absurd. There’s a mixture of deference and irony in the act which, along with the frisson of borrowed fame or ignominy, invites us with wry humour to question our values.

Avoided Object, 1999 similarly relies on appropriation. Pictures of clouds scudding across the sky above the Imperial War Museum (pictured below right) were taken with a camera once used by the commandant of Auschwitz to photograph his family. Parker used infrared film to turn the sky black and suggest that the lens through which a mass murderer saw the world must inevitably produce a darker view.

In 2004 she revisited the idea of crushing silverware. Perpetual Canon 2004 (pictured below) is a ghostly circle of flattened instruments hanging at eye level. Trumpets, trombones, saxophones, bassoons and tubas gleam in the twilight of a single bulb – beautiful but useless. The air irrevocably squashed out of them, they pay silent homage to the raucous clamour of brass bands.

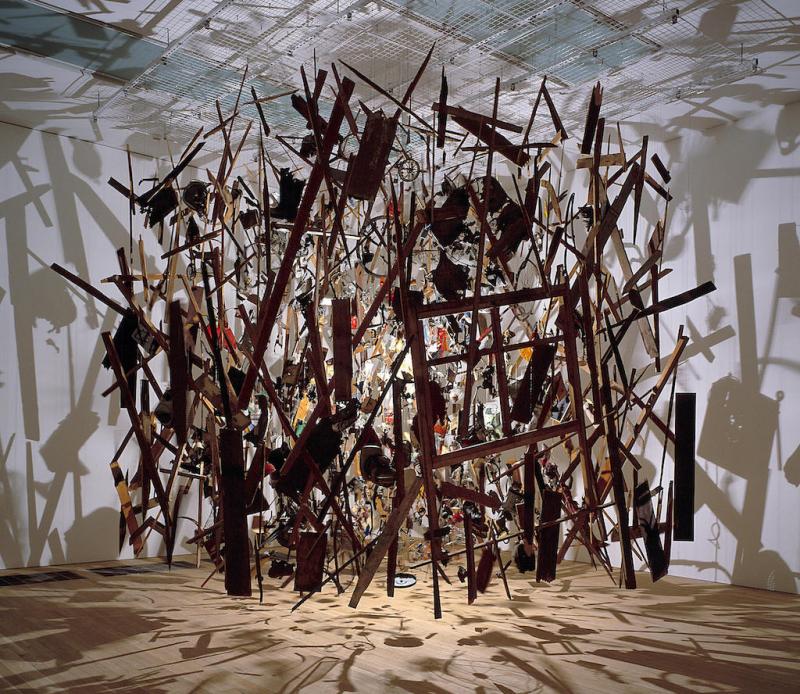

Her most famous act of creative vandalism, Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View 1991 (main picture) is as dramatic as ever. With the help of the Army and some Semtex, she famously blew up a shed and its contents, then collected the debris and hung each item from a thread. Framed by the splintered remains of the wooden shell, the accumulated clobber of daily life – bicycle wheels, tools, tins of paint, wellington boots, watering cans and the like – hang in the air as if caught mid-explosion. Lit by a single bulb suspended in the middle, they throw ghostly shadows over the surrounding walls and ceiling.

Her most famous act of creative vandalism, Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View 1991 (main picture) is as dramatic as ever. With the help of the Army and some Semtex, she famously blew up a shed and its contents, then collected the debris and hung each item from a thread. Framed by the splintered remains of the wooden shell, the accumulated clobber of daily life – bicycle wheels, tools, tins of paint, wellington boots, watering cans and the like – hang in the air as if caught mid-explosion. Lit by a single bulb suspended in the middle, they throw ghostly shadows over the surrounding walls and ceiling.

The initial thrill of the piece came from the dizzying spectacle of this frozen-in-time act of demolition. Since then, though, the work has accrued further meaning. Now it feels like an ironic comment on a way of life which encourages endless accumulation and the waste of precious resources. Seeing all this stuff blown sky high feels incredibly liberating; it makes you want to dance on the cracks between the paving stones.

That small act of rebellion inspired Black Path 2013. The route to her daughter’s school went through Bunhill Fields, the non-conformist burial ground in Islington where mother and daughter would play “don’t step on the lines”. Pouring liquid rubber into the joints and letting it harden enabled the artist to make a record of the cracks which she then cast in bronze. Standing on pegs so it hovers just above the floor, the resulting grid is a tantalising reminder of games that can be played and rules broken.

Parker’s work is inspired by the zeitgeist, but it is never overtly political. Made especially for the exhibition, FLAG was filmed in a Swansea factory. The video records the creation of a Union Jack from disparate strips of cloth to the finished product proudly flying at top mast. But the film is reversed, so we see the flag being lowered before gradually unravelling into its constituent parts. World Coming Apart 2017 is similarly telling. The photograph shows a worn map of the world mended along the folds with bits of sellotape that have turned yellow and begun to fray. Both works are brilliantly understated reflections on the possible disintegration of the United Kingdom and the waning health of our planet.

Parker’s work is inspired by the zeitgeist, but it is never overtly political. Made especially for the exhibition, FLAG was filmed in a Swansea factory. The video records the creation of a Union Jack from disparate strips of cloth to the finished product proudly flying at top mast. But the film is reversed, so we see the flag being lowered before gradually unravelling into its constituent parts. World Coming Apart 2017 is similarly telling. The photograph shows a worn map of the world mended along the folds with bits of sellotape that have turned yellow and begun to fray. Both works are brilliantly understated reflections on the possible disintegration of the United Kingdom and the waning health of our planet.

Island 2022 (pictured below), the last work in the show, consists of a greenhouse covered in dabs of chalk collected from the white cliffs of Dover. “The glass house,” Parker explains, “becomes enclosed, inward looking, a vulnerable domain, a little England with a cliff-face veil.” Lining the floor are old tiles rescued from the Houses of Parliament, their pattern rubbed away by the comings and goings of generations of MPs – democracy worn thin?

The work is a response to Brexit and the insularity it has spawned; but it also addresses climate change and the need to protect ourselves from global warming. “The spectre of the climate crisis is looming large”, says Parker. “With crumbling coastlines and rising sea levels, things seem very precarious… What was stable is now uneasily shifting.” Such serious issues are too gargantuan to deal with in tandem, though, and the installation feels as heavy handed as a mixed metaphor.

What makes Cornelia Parker’s work such a joy is her disinterested yet lighthearted approach; but this seems ever harder to maintain. How to respond to problems such as the failure of governments to take meaningful action on climate change, the Republicans’ daily assault on democracy or the Tories’ “let them eat cake” response to soaring inflation may well prove to be a challenge too far. And that would be very sad indeed.

What makes Cornelia Parker’s work such a joy is her disinterested yet lighthearted approach; but this seems ever harder to maintain. How to respond to problems such as the failure of governments to take meaningful action on climate change, the Republicans’ daily assault on democracy or the Tories’ “let them eat cake” response to soaring inflation may well prove to be a challenge too far. And that would be very sad indeed.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Add comment