Into the Night: Cabarets and Clubs in Modern Art, Barbican review - great theme, disappointing show | reviews, news & interviews

Into the Night: Cabarets and Clubs in Modern Art, Barbican review - great theme, disappointing show

Into the Night: Cabarets and Clubs in Modern Art, Barbican review - great theme, disappointing show

Artists's clubs - a vibrant topic dryly realised

The Barbican’s latest offering – a look at the clubs and cabarets set up by artists mainly in the early years of the 20th century – is a brilliant theme for an exhibition.

If artist’s studios are spaces primarily for solo achievement, where great artworks are produced and reputations made, these clubs were social spaces that fostered collaboration. The intention was to have fun, exchange ideas and change attitudes. The artists danced, sang, produced plays and puppet shows, turned themselves into living sculptures or recited nonsense poetry. Performance art was born, and a new form of political and cultural protest created.

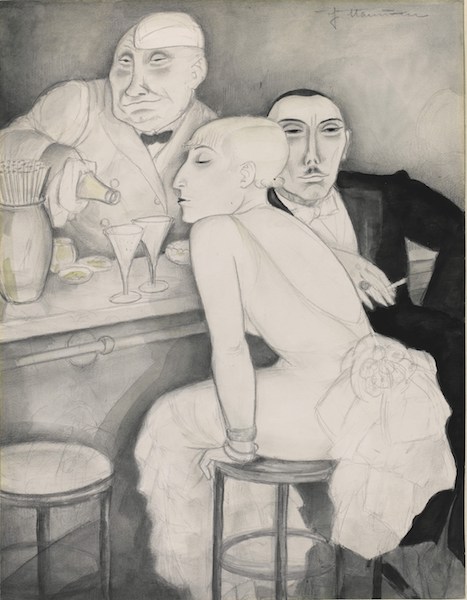

Each gallery is devoted to a single club except when it comes to Berlin. In the 1920s and ‘30s, the night club scene there became so frenetic that the government plastered the city with posters warning “Berlin stop and think, you are dancing with death”. George Grosz, Jeanne Mammen (pictured right: Bar, c. 1930 by Jeanne Mammen), Rudolf Schlichter and Max Beckmann recorded the nocturnal shenanigans in wonderfully acerbic paintings and graphics that are the highlights of the show. Valeska Gert appears on film performing expressionist solos in which she enacted uncouth behaviour. “Because I didn’t like solid citizens,” she is quoted as saying, “I danced those whom they despised – whores, procuresses, down-and-outs and degenerates.”

Each gallery is devoted to a single club except when it comes to Berlin. In the 1920s and ‘30s, the night club scene there became so frenetic that the government plastered the city with posters warning “Berlin stop and think, you are dancing with death”. George Grosz, Jeanne Mammen (pictured right: Bar, c. 1930 by Jeanne Mammen), Rudolf Schlichter and Max Beckmann recorded the nocturnal shenanigans in wonderfully acerbic paintings and graphics that are the highlights of the show. Valeska Gert appears on film performing expressionist solos in which she enacted uncouth behaviour. “Because I didn’t like solid citizens,” she is quoted as saying, “I danced those whom they despised – whores, procuresses, down-and-outs and degenerates.”

Precious little footage exists, though, of such.performances designed to get up the noses of “solid citizens”, whom the artists scorned and held responsible for the horrors of World War I. Of course, for anyone trying to recreate the ambiance and ethos of the clubs, this creates real problems. The curators have done sterling work, however, in bringing existing material together. Sketches, designs, prints, watercolours, paintings and occasional snippets of film give some idea of the aesthetics of each venue.

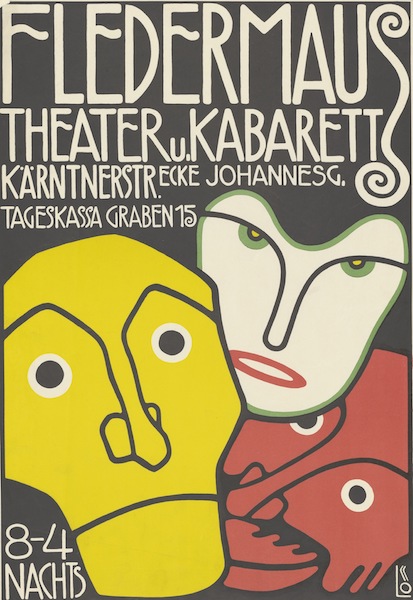

The main surprise is the substantial effort that went into setting up and running many of the clubs. Far from being pop-up venues, places like the Cabaret Fledermaus in Vienna and L’Aubette in Strasbourg were architect-designed establishments intended to last. In 1907, members of the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshop), transformed the basement of a residential building into Cabaret Fledermaus. They lined the walls with 7,000 brightly coloured tiles portraying animals, birds, plants and people as well as abstract patterns while Josef Hoffmann designed everything from carpets, chairs, vases, ashtrays and pepper mills to the distinctive metal pins worn by the waiters. Ambitious productions like Oscar Kokoschka’s play The Speckled Egg, performed on the opening night, were publicised with eye-catching posters and accompanied by beautifully designed programmes. (Pictured below left: poster for the Cabaret Fledermaus,1907 by Bertold Löffler)

This dazzling space has been recreated at the Barbican (main picture) next door to the dance hall-come-cinema designed by modernist architect Theo van Doesburg for L’Aubette in Strasbourg. In 1928, along with Sophie-Taeuber and Jean Arp, who had been involved in the Cabaret Voltaire, he converted a military barracks into a vibrant cultural centre complete with ballrooms, restaurants, bars, a tea room and cabaret. The walls and ceilings of the ballroom were covered with diagonal slabs of abstract colour which, along with films projected onto the wall, created a sense of constant dynamic shift that was deliberately unsettling.

This dazzling space has been recreated at the Barbican (main picture) next door to the dance hall-come-cinema designed by modernist architect Theo van Doesburg for L’Aubette in Strasbourg. In 1928, along with Sophie-Taeuber and Jean Arp, who had been involved in the Cabaret Voltaire, he converted a military barracks into a vibrant cultural centre complete with ballrooms, restaurants, bars, a tea room and cabaret. The walls and ceilings of the ballroom were covered with diagonal slabs of abstract colour which, along with films projected onto the wall, created a sense of constant dynamic shift that was deliberately unsettling.

These recreations are extremely impressive, but they are also empty shells. People are attracted to clubs mainly by the atmosphere, the very thing you can’t capture with silent objects and architectural settings. Audiences were drawn in hordes to the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich on whose tiny stage anarchy reigned. They came to be shocked, amused or outraged, but the exhibition captures none of this excitement. A couple of masks and a few minutes’ footage of Tristan Tzara, Richard Huelsenbeck and Marcel Janco declaiming nonsense and Hugo Ball reciting a sound poem don’t begin to convey the provocative atmosphere that brought so many punters flocking. To provide further glimpses of the experiments on offer, the curators might have included Kurt Schwitter’s Urs Sonata, Luigi Russolo’s Futurist sound organs and another Hugo Ball sound poem, all of which are available, even if they were recorded elsewhere.

Without more, desperately needed animation, the exhibition feels like a book on the walls – worthy but essentially lifeless.

- Into the Night: Cabarets and Clubs in Modern Art at the Barbican until 19 January 2020

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment