Trouble in Tahiti/A Dinner Engagement, Royal College of Music review - slick, witty and warm | reviews, news & interviews

Trouble in Tahiti/A Dinner Engagement, Royal College of Music review - slick, witty and warm

Trouble in Tahiti/A Dinner Engagement, Royal College of Music review - slick, witty and warm

Two 1950s one-acters come together in a stylish double-act

It’s a clever decision to pair Lennox Berkeley’s A Dinner Engagement with Leonard Bernstein’s Trouble in Tahiti. The first is all about happily-ever-after, while the second is all about what happens next. The optimistic grime and smog of 1950s London gives way to the shrink-wrapped brightness and professional happiness of the suburban American dream, smiles freeze into toothpaste-commercial grins and love curdles into quiet domestic despair.

A Dinner Engagement wrestles its happy ending to the ground by sheer persistence and determination. The parents are poor, the dinner is burnt, the daughter sulky and her pretty dress discarded, but still the prince falls madly in love and his mother waives the little matter of the dowry. There’s an innocence to the opera’s fairytale premise that could be cloying were it not for the wit and bathos of Paul Dehn’s libretto. (Dehn, incidentally, who is better known as the screenwriter of Goldfinger and The Spy Who Came in From The Cold.)

Jessica Cale (Susan) and Guy Elliott (Prince Philippe) are a couple whose happily ever after you really can believe in

He and Berkeley paint the fallen grandeur of Lord Dunmow and his household with affectionate detail and plenty of gentle mockery. Berkeley’s buzzy, playful score catches the rhapsodic yearnings of this impoverished former diplomat for his former days as a Minister Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to the Grand Duchy of Monteblanco, pulling the rug out from under its lyricism with plenty of bracing banality and chatter. Colanders, pickled walnuts, tomatoes and toast all cut against the contrived sweetness of the set-up, as does a wonderful cameo for domestic “treasure”, the voluble Mrs Kneebone.

Director Stephen Unwin takes a non-interventionist approach to a work you can just wind up and let go. If neither he nor conductor Michael Rosewell always coax every twitch and scuttle of comedy from its encounters, it makes for a gentler romance rather than a full-frenzy chaotic farce. Nicky Shaw’s designs lovingly recreate the Dunmow’s Chelsea basement kitchen, full of props (including a working hob) for the young cast to play with.

Director Stephen Unwin takes a non-interventionist approach to a work you can just wind up and let go. If neither he nor conductor Michael Rosewell always coax every twitch and scuttle of comedy from its encounters, it makes for a gentler romance rather than a full-frenzy chaotic farce. Nicky Shaw’s designs lovingly recreate the Dunmow’s Chelsea basement kitchen, full of props (including a working hob) for the young cast to play with.

Edward Jowle (pictured above with Laura Hocking as Mrs Kneebone) catches the wistful regret of Lord Dunmow, his warm, graceful baritone carving curves out of even Berkeley’s most angular lines. He’s ably partnered by soprano Katy Thomson – her practicality nicely coloured with just a hint of romantic regret. Jessica Cale (Susan) and Guy Elliott (Prince Philippe) are a couple whose happily ever after you really can believe in, charming without being arch or sending up this soufflé-light love story, and there’s comic support from Rebekah Jones’ batty Grand Duchess and Laura Hocking’s cockney Mrs Kneebone.

All the detail is stripped away for Trouble in Tahiti. Walls are removed and only their frames remain, allowing us to see through to the video screen behind that projects black and white fantasies of suburban America – white picket fences and all. It’s a slick setup for Bernstein’s artful one-acter, a sequence of duets and monologues for husband and wife Sam and Dinah elegantly strung together on a glittering musical thread provided by a jazz trio.

Immaculately, stylishly sung and danced here by Ffion Edwards, Samuel Jenkins and Will Diggle (costumed as three anonymous factotums, whose white-gloved hands are always ready to proffer orange juice or take a handbag), they offer the “bright falsehood” – sanitised, censored, ever-smiling – against which Sam and Dinah’s troubled lives are measured.

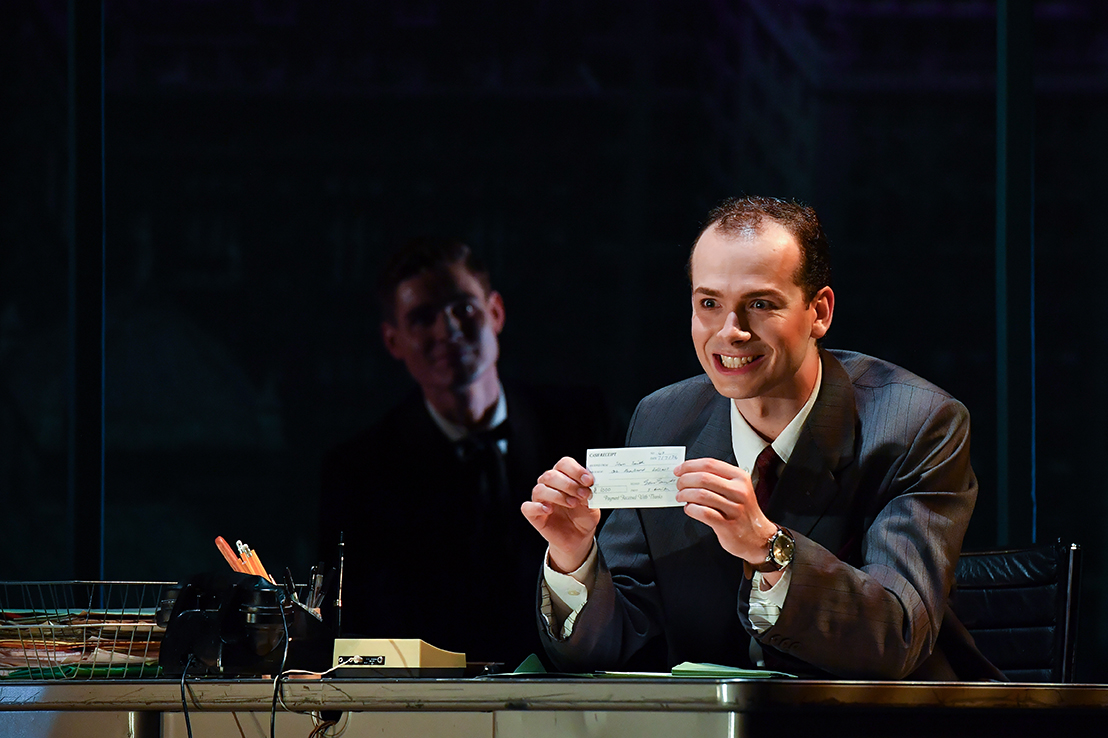

James Atkinson (picture above) and Holly-Marie Bingham mine plenty of quiet horror from their scenes. Atkinson seethes with toxic masculinity in his gym, his slightly rigid baritone bringing plenty of tension to Sam’s self-conscious performance of a life, while Bingham bares her soul passionately on the therapist’s couch. Dinah’s illicit afternoon movie-going climaxes in a brilliant song-and-dance number – a moment of blissful fantasy before the opera’s quiet, uncertain return to reality. Just as we give up, Bernstein opens the door to hope just a chink. We know it’s futile but still cling on, fingers braced for the inevitable slam. It’s devastating stuff, and handled here with a killer combination of slick efficiency and messy human detail.

James Atkinson (picture above) and Holly-Marie Bingham mine plenty of quiet horror from their scenes. Atkinson seethes with toxic masculinity in his gym, his slightly rigid baritone bringing plenty of tension to Sam’s self-conscious performance of a life, while Bingham bares her soul passionately on the therapist’s couch. Dinah’s illicit afternoon movie-going climaxes in a brilliant song-and-dance number – a moment of blissful fantasy before the opera’s quiet, uncertain return to reality. Just as we give up, Bernstein opens the door to hope just a chink. We know it’s futile but still cling on, fingers braced for the inevitable slam. It’s devastating stuff, and handled here with a killer combination of slick efficiency and messy human detail.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Add comment