Dan Cruickshank: Resurrecting History – Warsaw, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

Dan Cruickshank: Resurrecting History – Warsaw, BBC Four

Dan Cruickshank: Resurrecting History – Warsaw, BBC Four

The traumatic story of the Polish capital's World War Two destruction and subsequent restoration

Dan Cruickshank, that enthusiastic architectural historian, who likes nothing better than some scaffolding he can clamber up to get a better look, revealed that as a child of seven he moved some 60 years ago to Warsaw with his family. His father, then a member of the Communist Party, was posted to the Polish capital by the Daily Worker as their correspondent.

The young Cruickshank took to his adventure with alacrity. He precociously drew the view over Old Warsaw visible from his family’s apartment. Visiting his old home 60 years later, there was the view again to compare to his preserved childish drawings. And it was this early experience of Warsaw that inspired his own passion for architecture.

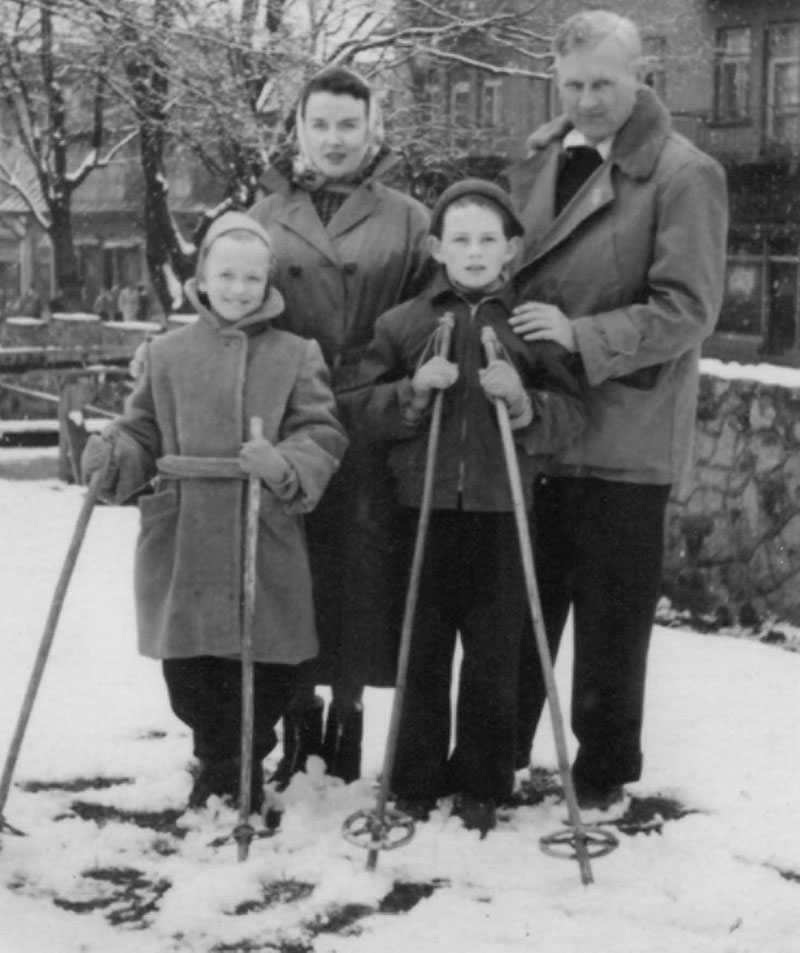

His walk back into his own childhood was reinforced by some surprisingly tasteful re-enactments in black and white of a 1950s costumed boy walking through the Warsaw streets. Cruickshank has a passion for the Poles, not to mention their version of wiener schnitzel, which the family used to have for Sunday lunch in a café which Cruickshank revisited for the cameras. He reminded us of the terrible history that has been obscured by time and newer terrible events. Warsaw was one of the great cities of the 18th century, and with barely suppressed fury he narrated its almost total destruction by the Nazis (pictured above, Cruickshank, second from right, and family in Warsaw in 1957).

His walk back into his own childhood was reinforced by some surprisingly tasteful re-enactments in black and white of a 1950s costumed boy walking through the Warsaw streets. Cruickshank has a passion for the Poles, not to mention their version of wiener schnitzel, which the family used to have for Sunday lunch in a café which Cruickshank revisited for the cameras. He reminded us of the terrible history that has been obscured by time and newer terrible events. Warsaw was one of the great cities of the 18th century, and with barely suppressed fury he narrated its almost total destruction by the Nazis (pictured above, Cruickshank, second from right, and family in Warsaw in 1957).

It was, of course, the invasion of Poland that triggered the cataclysmic events of World War II. It was in revenge for the Warsaw Uprising of 1944, when the patriotic Poles were betrayed by the Russians as well, who wanted the independence of Poland fatally compromised, that the Germans finally managed to complete their annihilation of the city. Some 90 per cent was destroyed; the great libraries were systematically burnt. The archival photographs are heartbreaking, and eyewitnesses reported horrors. One survivor who herself when a teenager had taken to the streets to fight spoke eloquently of the spirit of the time. Another, a young girl, was scarred by seeing a mother and child run out of a burning building, only to be systematically murdered. The Poles were to be slaughtered, as well as the city in which they lived. Hundreds of thousands lost their lives.

Cruickshank reminded us several times why and how the Nazis had tried to wipe Warsaw off the map, and showed us a most remarkable plan from a German architect as early as 1939 for a small, banal town with which they were planning to replace the destroyed Warsaw. The capital of Poland would be no longer beautiful, significant and important, and the country would be Germanised (fighters in the 1944 Warsaw Uprising, pictured below).

What and how should you preserve, conserve and restore? And how and why after the war did the Soviets sanction – or at least allow to go ahead – the extraordinary grass roots movement to rebuild the destroyed Old Town with its colourful buildings, replete with exuberant baroque decoration, lions and dragons, gods and goddesses? Because, said the Russians, you cannot progress unless you have the visible background of history to build on.

What and how should you preserve, conserve and restore? And how and why after the war did the Soviets sanction – or at least allow to go ahead – the extraordinary grass roots movement to rebuild the destroyed Old Town with its colourful buildings, replete with exuberant baroque decoration, lions and dragons, gods and goddesses? Because, said the Russians, you cannot progress unless you have the visible background of history to build on.

Cruickshank also showed us an astonishing trove of detailed architectural drawings made by students in the 1930s. These, combined with the 18th century Bernado Bellotto paintings of Warsaw (a royal commission), which had miraculously survived the material and human carnage, gave the huge restoration movement a great deal of information. It also transpired that many architectural fragments, decorations and the like, had been smuggled out during the war, to a country church, and hidden in monks’ coffins. You could not make it up – or could you?

In an attempt perhaps to impress on us the singularity of the rebuilding of Warsaw’s Old Town (below, Warsaw in 1773, by Bernardo Bellotto), Cruickshank did not mention that other unimaginably ambitious rebuilding programme: of the so-called suburban palaces which ring St Petersburg, from Peterhof to the Catherine Palace, all burnt by the Germans as they retreated from the then-Leningrad. After the war these great estates and buildings were restored to Tsarist glory at a time when Russia was economically on its knees.

This must still rank as the biggest restoration programme ever, perhaps more even than Warsaw and Dresden, the latter also unmentioned by our tour guide. Perhaps this omission was meant to underline the grassroots nature of the restoration. The rebuilding of the Old Town was not a state-led restoration, but was sparked by the spontaneous determination of ordinary Warsovians. They rebuilt, as photographs and films showed us, with minimal resources, by hand. An eyewitness remembers as a child that her family’s greatest treat was going on Sunday to the building sites to help sift for remnants of original bricks. As a little girl she could only help by finding the lightest of these fragments, which she did with great enthusiasm.

This must still rank as the biggest restoration programme ever, perhaps more even than Warsaw and Dresden, the latter also unmentioned by our tour guide. Perhaps this omission was meant to underline the grassroots nature of the restoration. The rebuilding of the Old Town was not a state-led restoration, but was sparked by the spontaneous determination of ordinary Warsovians. They rebuilt, as photographs and films showed us, with minimal resources, by hand. An eyewitness remembers as a child that her family’s greatest treat was going on Sunday to the building sites to help sift for remnants of original bricks. As a little girl she could only help by finding the lightest of these fragments, which she did with great enthusiasm.

The restoration was against the background of the hideous new estates for the bureaucrats and workers, its centre piece the Palace of Culture, at 231 metres the tallest building in Warsaw, a dispiriting conglomeration, as I can personally attest. Poles, then as now, were profoundly patriotic (in 1974, their best loved film, never released in the West, was the romantic Hubal, named after the calvary officer who in 1939 took his regiment, the last such remaining, to the woods, fighting with his men and horses to the death as the Germans invaded). Their history is scarred by their powerful neighbours to east and west who all too often simply walked in and appropriated as took their fancy. Resistance is the Poles' second nature.

Cruickshank pointed out now that there is an economic revival, meaning of course that the Warsaw skyline is growing to resemble that of any other large city. But the colourful streets of the Old Town are here too; Warsaw had successfully risen from the dead, a resurrection indeed. The subject, as Cruickshank wisely reminded us, is painfully timely when once again historic buildings and artifacts, embodying memory, are destroyed as warring factions attempt to obliterate the past, the better to subjugate their victims.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

Add comment