Julia Margaret Cameron, Victoria & Albert Museum / Science Museum | reviews, news & interviews

Julia Margaret Cameron, Victoria & Albert Museum / Science Museum

Julia Margaret Cameron, Victoria & Albert Museum / Science Museum

Experimental and unorthodox: the extraordinary life of a pioneer of early photography

Reputations and popularity rise and fall and rise again in cycles, and so with the redoubtable Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879). Now considered one of the finest photographers ever, she was an amateur gifted with incredible tenacity, intellectual and physical energy, and stamina. Stubborn and ambitious, for her class and gender she was unusually interested in business.

One of the seven Pattle sisters – classical Victorians famous for being adventurous, original and full of vitality – Julia became friends with the intelligentsia, the literati, even the glitterati. Her siblings were so beautiful that sometimes crowds gathered when they made a public appearance. Julia Margaret was the only one considered plain; brought up in India, the sisters also unnerved their peer group by chattering in Hindustani to each other.

Julia married Charles Hay Cameron, one of the most distinguished of Indian civil servants, whom she met in South Africa. He was 20 years her senior although he outlived her; they had six children, and she pursued what earnings she could to help with her sons’ education. Her sister Sarah Prinsep masterminded a sensationally successful salon at her London house, Little Holland House, attended by everybody who was anybody, many of whom became friends and even mentors of Julia.

Julia married Charles Hay Cameron, one of the most distinguished of Indian civil servants, whom she met in South Africa. He was 20 years her senior although he outlived her; they had six children, and she pursued what earnings she could to help with her sons’ education. Her sister Sarah Prinsep masterminded a sensationally successful salon at her London house, Little Holland House, attended by everybody who was anybody, many of whom became friends and even mentors of Julia.

Notable among them was the artist GF Watts, who, as this revelatory new exhibition at the V&A’s spacious Photography Gallery reveals, was one such artistic mentor. She sent samples to her portrait painter friend for enlightened criticism, and this fascinating dialogue is explored here.

Many of her so called imperfect photographs – she was endlessly criticised at the time by male photographers – were deliberately so, since she was endlessly curious and eager to experiment. She also engaged professionally with Sir Henry Cole, the inventive and enlightened first director of the V&A. The first museum to provide both cafés and sanitary facilities for its visitors, the V&A was also the first to collect and exhibit photography, a medium only invented about a decade before the museum’s foundation.

Cameron wrote remarkable letters to Cole in her large, very legible handwriting, her eagerness and enthusiasm almost overwhelming. She gave some photographs to the museum, and the museum also purchased prints directly from her, carefully signed and mounted. Using the most advanced methods available, she used a large wooden camera, and the wet collodion process. Glass plates of say 12” x 15” had to be coated with chemicals and eventually contact-printed on chemically coated paper, the processes delicate, time consuming and finicky, with potential disaster at every stage.

For a time, Cole also offered her rooms at the museum itself, making Cameron perhaps the first artist-in-residence at any museum. When Cameron offered her photographs to the new museum, she wrote in her characteristically high spirits in a 16-page letter (big handwriting, small pages) that she intended her images to “electrify you and startle the world. I hope it is no vain imagination of mine to say that the like have never been produced & never can be surpassed!”

Her career faltered when the Camerons migrated to Ceylon; typically realistic, they sailed with their coffins

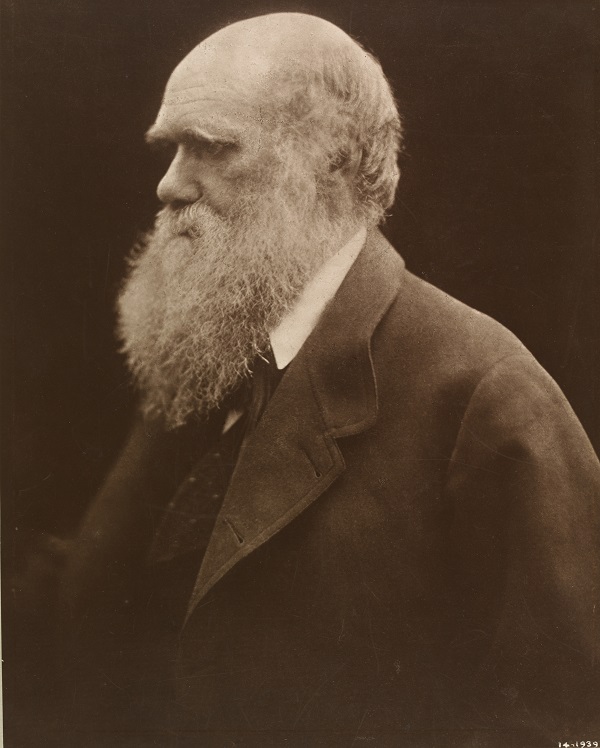

Almost without exception her close-cropped images, the faces occupying almost all the picture space, are portraits. There are portrayals of her extended family and the great and the good, Charles Darwin, Lord Tennyson, Thomas Carlyle, Robert Browning, Sir John Herschel and Anthony Trollope among them (pictured above right: Charles Darwin, 1868).

Often, she insisted on arranging small groups of servants, relatives and friends into tableaux based on mythological, historical and biblical tales. Here and in her portraits the women are beautiful, at times wistful and tenderly poignant, with a kind of gossamer strength, the men bearded and brilliantly intense.

A strong affection shines out from her portraits of babies (her grandchildren among them) and young children are dignified and subtly charming. The tableaux, mimicking the subjects of Old Master and Victorian paintings, seem at times risible to modern eyes; their subjects, commanded to stay still, evidently occasionally dissolved in giggles, her spear-carrying husband among them. Needless to say, Mrs Cameron had an extensive dressing-up box (main picture: Whisper of the Muse, 1865).

The entire spectrum is on view at the V&A, drawn from its own holdings and amplified by the discovery of an image of Cameron’s Glass House. When she returned from India to live in England, one of her daughters gave her notoriously energetic mother a camera to ease her supposed isolation, hoping, presumably, to keep her out of mischief – an ambition that was not achieved. The Glass House was in fact the family’s chicken coop; the disgruntled birds were evicted so the neat little building with its extensive glazing could be turned into a studio. Her darkroom was the coal hole. Mrs Cameron’s handful of notes for an autobiography, high-flown yet self-deprecating, is simply called Annals from the Glass House and its manuscript is on view at the Science Museum.

Her career faltered when for financial reasons, the Camerons migrated to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) to the family’s coffee plantations in the hills; typically realistic, they sailed with their coffins. The heat and the difficulties of supplies diminished her output and her last few photographs are of the plantations and their native staff.

Her career faltered when for financial reasons, the Camerons migrated to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) to the family’s coffee plantations in the hills; typically realistic, they sailed with their coffins. The heat and the difficulties of supplies diminished her output and her last few photographs are of the plantations and their native staff.

Some of the portraits are truly haunting in their poignant beauty and wistful allure. Julia Jackson, her niece, is perhaps typical of Mrs Cameron’s empathy and visual imagination (pictured right). She is a beautiful young woman; her hair streams down in a cascade on either side of her face, her eyes are wide and gazing out at us with a look both direct and enigmatic. Her daughter, Virginia Woolf, Mrs Cameron’s great niece, returned the compliment with a book she wrote with Roger Fry in 1926, called Victorian Photographs of Famous Men and Fair Women, the title a fair summary of Mrs Cameron’s subjects.

The sheer implacable intensity of the gaze of several of her male subjects, glittering with intelligence or perhaps just the strain of the pose, give us fine renderings of the great Victorian intellectuals. The pose is typically oblique, seen in three-quarters or complete profile, the sideways gaze intensifying the thoughtfulness of the expression which is absorbed in contemplation and looking far beyond us. She deployed wonderful contrasts of light; the background is undifferentiated, the head the focus, with flickering, dappled shadowing over part of the face contrasting with glowing skin and eyes and the texture of the hair.

On show at the Science Museum’s Media Space is the Herschel Album, 1864, comprising 94 prints which Mrs Cameron had made to give to her great scientist friend (inventor not only of the blueprint but of the very word "photography"). When the family sold it at Sotheby’s to an American collector in 1974 it made £52,000, an immense surprise at the time. The publicity gave impetus to the Cameron revival, and the album was then saved for the nation: a compendium of portraits of the great and the good and her tableaux, it is a fine complement to the V&A exhibition.

Julia Margaret Cameron at the Victoria & Albert Museum until 21 February and the Science Museum until 28 March

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment