We Made It: Bex Burch, Dagaare Xylophone-Maker | reviews, news & interviews

We Made It: Bex Burch, Dagaare Xylophone-Maker

We Made It: Bex Burch, Dagaare Xylophone-Maker

Percussionist explains how the unique craft and culture of a north-Ghanaian people shapes her music

Bex Burch is a percussionist with a classical training at the Guildhall School of Music. First visiting Ghana as an undergraduate, on the recommendation of a Ghanaian friend, she initially felt very uncomfortable there, but gradually grew to love the people, the way of life, and the musical culture. Settling in the north, with the Dagaare People, for two years after graduation, she began an apprenticeship with Thomas Segkura, a professional maker of Dagaare xylophones, or gyilli.

Although he was responsible for musical performance in Dagaare society, Thomas’ role was known publicly as gyil-maker, and the construction of the instruments, whose keys are made from sacred lliga wood, formed a crucial part of the apprenticeship. The instrument’s distinctive buzzing sound comes from the used of dried gourd resonators, which hang below the keys. Since returning to UK, she continues to make and sell gyilli. She uses both lliga wood she brought back from Ghana, but also experiments with British varieties. She now plays gyil in Vula Viel, a band she leads containing many of the up-and-coming stars of the London jazz scene, including saxophonists Tom Challenger and George Crowley, vibes player Jim Hart, and drummers Dave De Rose and Simon Roth, playing music loosely classified as world jazz, which is often inspired by or based on Dagaare rhythms.

BEX BURCH: The first piece I put on in college was Steve Reich’s “Sextet for Six Marimbas”. It’s such a powerful piece of music. By training I’m a classical percussionist. I came straight out of college and began playing in orchestras. My first gig was with the Philharmonia at The Royal Festival Hall. Playing with that level of musicians is exhilarating. When music comes together, it’s magical.

They believe a member of the Dagaare was kidnapped by fairies and shown the secrets of making xylophones

I was 18 when I first heard Ghanaian music. I was playing Beethoven at the time, who’s a great writer for timpani. Rather than using rhythm as an exercise, Beethoven used timpani in harmonically complex ways. The magic happens when you understand why the piece is written like that. I was searching for more in my own playing, which led me to Reich, then Ghana. His marimba rhythms resonated with me, and they were inspired by Ghanaian music. A lot of wanky contemporary marimba music doesn’t interest me. but Reich is really good. I went to Ghana not as a rejection of my orchestral background, but because I love different genres.

Ghanaian music is based on the bell pattern [an asymmetrical rhythmic pattern found throughout sub-Saharan Africa], which I love, and need in own writing. Its power, which is thousands of years old, is that it can be subdivided in different places, with three foundations based on asymmetry or chaos, not just a Western 4/4.

I was 19 when I first went to Ghana. I found it really difficult, it got under my skin. I didn’t like the food, it was too hot, and people were shouting all the time. The language is a shouty, command-based language, with a completely different grammatical basis, which informs how the music is written.

I went for a month initially, and hated it. Then I did my second year at college, but Ghana was under my skin. I mentioned to my tutor that I wanted to go back to Ghana for a year, and got funding for a proper visit. I took a year out of Guildhall, and that’s when I first went to the north and had the space to take in how I was reacting. I went from separate to connected in terms of language, food, heat, shouting, and I just loved it. I really enjoyed the heat, and got really used to sweating in bed. It began to feel homely, so much so that I used to wear a jumper in bed back here to recreate that feeling. I got to know a farming family and took part in harvesting and making food. Preparing a meal takes all day because you can’t buy stuff, you have to grow it, but being involved in that process makes it delicious – the connection is crucial.

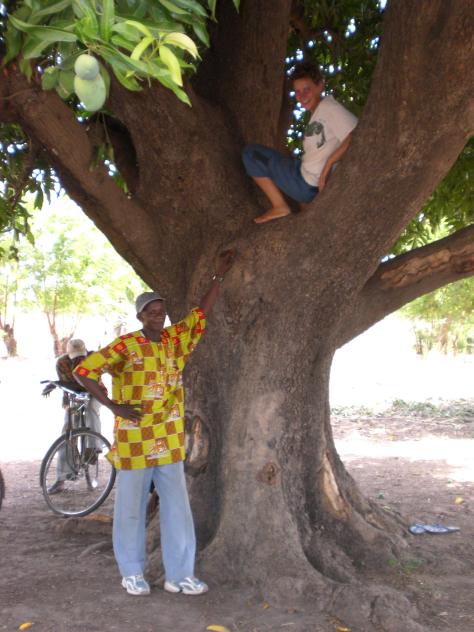

I met Thomas (pictured right, with Bex in a mango tree) who became my apprentice-master, early on that year. I went to the north with the help of musicologist Trevor Wiggins, who put me in touch with Chief Nandom Naa (which translates as the “Chief of Nandom”). It was the first rural part of Ghana I’d been to, and something resonated emotionally. When I met Thomas something resonated with him, and with the xylophones, gyil (plural “gyilli”) the first time I heard that instrument.

I met Thomas (pictured right, with Bex in a mango tree) who became my apprentice-master, early on that year. I went to the north with the help of musicologist Trevor Wiggins, who put me in touch with Chief Nandom Naa (which translates as the “Chief of Nandom”). It was the first rural part of Ghana I’d been to, and something resonated emotionally. When I met Thomas something resonated with him, and with the xylophones, gyil (plural “gyilli”) the first time I heard that instrument.

At first Dagaare gyilli music was impossible to follow, even for a professional percussionist. There were two xylophones and a tom-tom, but the musicians were surrounded by singers and dancers. With a lot of West African music, musicians serve the masses: you are there to enable celebration or grieving, and dancing. There is less celebrity in being a musician, and less money than in UK, but there is respect. The utilitarian playing at funerals, for example, is so important. Music enables everyone to work through issues.

Dagaare music is more complex than the music of the Ewe People, where Steve Reich went in eastern Ghana. Lots of academics have written about that music, which uses the same bell pattern. I could sit down next to any of the single Ewe parts and in some way understand what was going on. With Dagaare music, all those separate parts are in one player, and you have to really know it. It’s hard, and you have to be fully committed. It is inclusive, though. They accepted me as a white woman.

I came back to complete my degree at Guildhall, but I knew when I left Ghana, I wanted to come back, so I applied for the Isserlis Award, through the Royal Philharmonic Society. It’s a biennial award, and that year (by chance) it was designated for a percussionist. They believed in me, and they saw something in what I wanted to do. It’s supposed to fund two years’ study anywhere except England. I told them I’d been accepted as apprentice to Thomas.

I woke up from a ketamine trip singing, “The gyilli beat me.”

It took two weeks solid to make a xylophone in Ghana. I was working with lliga wood, which comes from a small bushy tree. It’s short, gnarly, witchy-looking, poisonous red wood. They believe that a member of the Dagaare People was kidnapped by fairies and shown the secrets of making xylophones. My apprenticeship was in making. Makers are more dangerous, because they’re closer to the spiritual aspect of the wood. They make sacrifices to appease the spirit world: when you finish a xylophone you sacrifice a black cockerel and a male guinea fowl. Having kept and killed animals that are kept for the nourishment of the community in a sustainable way, I could accept that. Playing instruments for Dagaare funerals also needs a sacrifice, but in UK it’s not necessary. Maintaining instruments for people could also be dangerous, and we had to ask for guidance from the witch doctor.

Part of the initiation is that the gyil beats you. Lliga wood has a powerful spirit, and I didn’t go in with the respect for the wood that I should have. It teaches you it’s boss. One of my blisters became infected with poison from the wood, and I didn’t sleep for four days. I was delirious, my hand swelled up, and I was in lots of pain. I had amazing visions. People in the village tried to help, but in the end I was taken to hospital. I woke up from a ketamine trip [injected by the hospital doctor] singing, “The gyilli beat me.” I found out later that I’d nearly lost my hand.

The understanding of everything about the gyil has come through the making. Hard physical work used to be difficult, but in Ghana I started really loving work. There it’s a part of growing up. I earned my respect and responsibilities. I took pride in being able to lift more stuff and use my body. Women aren’t weaker, but they have a different strength. Women in Ghana carry a huge amount of water on their head through strength and grace.

Though I’d grown up as a strong female percussionist, and I hadn’t wanted to be a man, it wasn’t obvious to me how femininity was connected with strength. I realised in Ghana that the rhythm and practical beauty of making stuff was really important, and I started to enjoy having my arms busy from working. I wanted to do this work because it made me feel like a capable woman. Thomas didn’t have to work after I got there, he always took the view that you’re definitely meant to be doing this.

Now, I really look forward to working. I love the responsibility of standards. Every instrument I make gets better. There’s an endless gradient of improvement. I can’t sell an instrument I’m not happy with. If a key’s a bit sharp or flat, it’s not sanded properly. This kind of responsibility is teaching me to cut through any sense of bullshit or entitlement. It’s a nice way to go about work.

The hardest work is tuning the lliga wood keys. Different bits of wood have a different density. The frame has four corners, and the string holding the keys needs to attach to the nodal point, the deadest point, with the least vibration. Between nodal points If you take wood off in the mid point of the key, it makes the note lower, because the key is more elastic. It seems incredible that the pitch can be changed by shaving off middle part.

The calabash gourds (pictured above: seen hanging beneath the keys) we use as resonators grow as weeds. The flesh is poisonous, but people collect them because they’re used for bowls. The skin is much stronger than pumpkin. The gourd is tuned to each key. Tuning a calabash is much simpler than a key, it’s most satisfying. You just set it on your knees, and shave it until the resonance suddenly appears. All of a sudden I have the sound.

The calabash gourds (pictured above: seen hanging beneath the keys) we use as resonators grow as weeds. The flesh is poisonous, but people collect them because they’re used for bowls. The skin is much stronger than pumpkin. The gourd is tuned to each key. Tuning a calabash is much simpler than a key, it’s most satisfying. You just set it on your knees, and shave it until the resonance suddenly appears. All of a sudden I have the sound.

I can tune a gyil however I like. Ghanaian tuning divides the octave into five equal intervals. I think it sounds funky, and a different sound world to the pentatonic tuning. When I’m making a Ghanaian-tuned gyil here, I do it scientifically with a tuner. I really enjoy that part of it. I also tune to play with other people using Western tuning. There are all kinds of other customisations I use. I can make one that fits into a car, for example. And I have wired my Gyilli up so that they plug into an amp! This is creativity, for me. Understanding the dynamics and context of your music is essential, I think.

When I passed out from the apprenticeship, the elders in the Dagaare tribe gave me a name, Vula Viel

I’m currently trying out other wood to use for xylophones. A tree surgeon is drying out sample logs for me, and I’m doing a taste test. Wood that’s died upright is especially good for instruments because it’s dried out really well. I still have some lliga samples that were shipped home. It has a story to it, a meaning for me. We did a cleansing on that wood before it was shipped, a cleansing of anything connected with funerals that could cause problems – reluctant spirits and so on. It means other people can work on it, and children can work with me. It won’t make me lose my hand. Now I have moved home, making xylophones from indigenous wood is also appealing. As a Yorkshirewoman, I’m interested in finding local wood to use.

When I passed out from the apprenticeship, the elders in the Dagaare tribe gave me a name, “Vula Viel”, which means “good is good”, with a naming ceremony. For the first five years you own your name, then your name owns you and guides you. It’s the same with music. I went to be an apprentice; I practised in the rain when no one could hear me; the first day I was allowed to play at a funeral, I felt I’d really earned it. I worked hard at making xylophones, and when I left, elders told me that all they has given me is mine, and all I have given them is theirs. It’s still sinking in.

There’s a chaos aspect of xylophone-making, just like music-making. I never know how an instrument is going to turn out. The gourds have holes in that we stick this special paper over. It has vibrations like a kazoo – the paper is very unpredictable. Likewise, the band isn’t just about me being in control, it’s about putting the administrative work in, organising rehearsals, emailing, and so on. I do that with joy, it’s work that needs doing like the labour of manufacturing the xylophone.

It helps my band-leading, having earned that respect for myself as a xylophone-maker, especially when I’m sorting out five men working together. I have no background in jazz, whereas most of the others are defined as jazz musicians. I’m enjoying that. My experience of jazz at college was that it involved learning a lot of rules, but I haven’t learnt those rules, so we don’t sound like every other jazz band. If you want to call us Jazz or World I don’t mind, so long as I’m making good music. I will respect my own creativity and put it out there. Not having learnt the rules gives me more self-belief.

Vula Viel rehearsed for eighteen months before we did a gig. Our harmony and chord changes are strict, following an asymmetrical pattern that takes 24 repeats, following a Dagaare structure. For the first time in my life, I’m not blagging. Something about Dagaare rules resonated with my creativity. It’s not a jam session, it’s not improvised, it’s just new. Dagaare music had that magic of coming together daily, that’s possible every day, it’s not something to put up with only once a month.

A lot of our music is based around things Thomas taught me. Many of our arrangements are from Thomas, from Ghana. They were written hundreds of years before I started. The Dagaare don’t talk about writing or composing, they copy tunes from others, but inevitably change them. Though we haven’t released our first album yet, I’m already writing a second set of tunes for keys, vibes, sax, drums, and for Vula Viel’s specific players and personality. I think our first album is powerful, but it’s been there for years. The second is mine.

- Vula Viel’s first album Vula Viel Good Is Good is released on 15 April 2015. There is more information about her xylophone-making on her website

Overleaf: listen and watch Bex Burch play the gyil with Thomas and her band Vula Viel

Many of Vula Viel's recent tracks are on their Soundcloud page

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more We made it

We Made It: Guitar Maker Brian Cohen

The incredible one-man string band

We Made It: Guitar Maker Brian Cohen

The incredible one-man string band

We Made It: Basket-maker Lois Walpole

Weaving works of art from 'ghost gear' and the detritus of consumerism

We Made It: Basket-maker Lois Walpole

Weaving works of art from 'ghost gear' and the detritus of consumerism

We Made It: Horn Maker Tom Fisher

Bespoke horns, handcrafted in a Derbyshire cellar

We Made It: Horn Maker Tom Fisher

Bespoke horns, handcrafted in a Derbyshire cellar

We Made It: Stufish Entertainment Architects

From U2 and Madonna to Chinese theatre and the Martian Fighting Machine

We Made It: Stufish Entertainment Architects

From U2 and Madonna to Chinese theatre and the Martian Fighting Machine

We Made It: 'Carol' Costume Designer Sandy Powell

How she brought a melange of styles to Todd Haynes's sublime period romance

We Made It: 'Carol' Costume Designer Sandy Powell

How she brought a melange of styles to Todd Haynes's sublime period romance

We Made It: Stuntwoman Tracy Caudle

Forget Evel Knievel: a well-crafted stunt is more about precision than daring

We Made It: Stuntwoman Tracy Caudle

Forget Evel Knievel: a well-crafted stunt is more about precision than daring

We Made It: 'The Revenant' Production Designer Jack Fisk

How he stunningly recreated the authentic American frontier of 1823

We Made It: 'The Revenant' Production Designer Jack Fisk

How he stunningly recreated the authentic American frontier of 1823

We Made It: Double Bass Maker Laurence Dixon

Love at first sight, a six-day week and the satisfaction of a job well done

We Made It: Double Bass Maker Laurence Dixon

Love at first sight, a six-day week and the satisfaction of a job well done

We Made It: The Electric Recording Company

Pete Hutchison's quest for musical perfection on vinyl

We Made It: The Electric Recording Company

Pete Hutchison's quest for musical perfection on vinyl

We Made It: Watchmaker Roger W Smith

The world-leading horologist keeping British watchmaking alive, crafting exquisite timepieces by hand

We Made It: Watchmaker Roger W Smith

The world-leading horologist keeping British watchmaking alive, crafting exquisite timepieces by hand

We Made It: Concert hall acoustics

The RSNO have a new concert hall. The lead acoustician explains why it sounds so good

We Made It: Concert hall acoustics

The RSNO have a new concert hall. The lead acoustician explains why it sounds so good

We Made It: The Headcaster App

Chris Chapman explains the genesis of his animated character app

We Made It: The Headcaster App

Chris Chapman explains the genesis of his animated character app

Add comment