Emily Carr, Dulwich Picture Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Emily Carr, Dulwich Picture Gallery

Emily Carr, Dulwich Picture Gallery

An exhibition celebrating Canada's unsung modernist

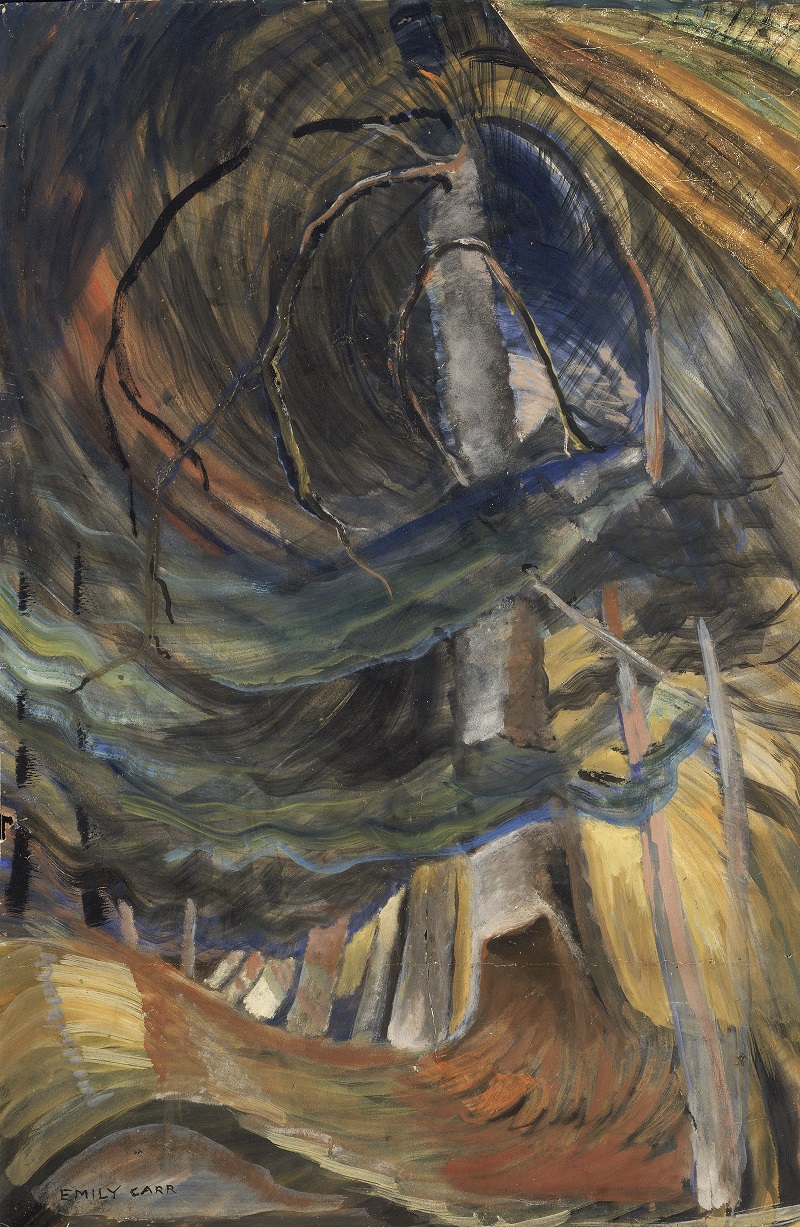

Walking into this exhibition is a bit like walking into a great forest. The dark green walls are hung all around with paintings of trees; we look up through branches that spiral dizzyingly skyward, while the upwards sweep of vast trunks seem relentlessly, tangibly full of life. Some of these paintings verge on abstraction, the forms of tree trunks simplified and reduced to an arrangement of planes, with spatial recession represented entirely through colour.

In their soulful evocation of the grandeur of nature, these late works by Canadian painter Emily Carr are the culmination of an entire career. Her love of the natural environment of British Columbia on Canada’s west coast is fused with a fascination for the native peoples of that region, whose culture and way of life was shaped by its great temperate rainforests and was, in Carr’s lifetime, threatened and marginalised as at no other time.

Her connection to this simultaneously specific and obscure location is presumably the reason why, outside Canada, no one has ever heard of Emily Carr. To Canadians, she is something of a national hero, regarded as a pioneering artist who embraced modernism and championed oppressed native cultures. But beyond her own borders, Carr's work has seemed excessively bound up with New World concerns, preoccupied with matters of identity and belonging that resonate only in a country that has been shaped by the traumas of colonial rule. (Pictured left: Tree (spiralling upward), 1932-1933)

Her connection to this simultaneously specific and obscure location is presumably the reason why, outside Canada, no one has ever heard of Emily Carr. To Canadians, she is something of a national hero, regarded as a pioneering artist who embraced modernism and championed oppressed native cultures. But beyond her own borders, Carr's work has seemed excessively bound up with New World concerns, preoccupied with matters of identity and belonging that resonate only in a country that has been shaped by the traumas of colonial rule. (Pictured left: Tree (spiralling upward), 1932-1933)

Nevertheless, it would be a terrible error to describe Carr as provincial. Born in 1871 in Victoria, British Columbia, Carr railed against a stiflingly conventional upbringing, and was single-minded enough to attend art school in San Francisco aged 18, before coming to study in London. Later, she lived in Paris for a couple of years, where she absorbed the vivid colours and expressive brushwork of Post-Impressionism, and had two paintings accepted at the Salon d’Automne of 1911.

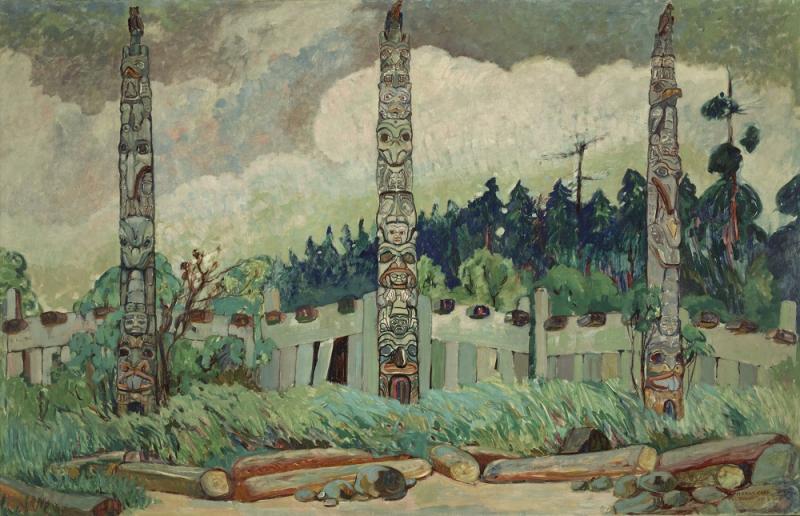

Having resolved a few years earlier to dedicate herself to recording the embattled native cultures of Canada’s west coast, Carr returned from Paris with a new energy. In watercolours of remote and often deserted settlements, Carr’s recent encounters with the Fauves are unmistakably evident. In Tanoo, Queen Charlotte Island, BC, 1913 (main picture), the bold, vigorous treatment of the overgrown grass and lush foliage contrast with the melancholy aesthetic of the piece. The forgotten totem poles, gradually being reclaimed by nature, are reminiscent of the picturesque ruins beloved of 19th-century English watercolourists.

For all Carr’s earnestly felt concern for Canada’s native peoples, as an artist and as a member of the colonial population, she could not help but aestheticise what she saw. Even her use of an avant garde European painting style to represent indigenous art underlines the disconnect between native and settler, a tension she acknowledged herself when she said, “I was as Canadian-born as the Indian but behind me were the Old World heredity and ancestry”.

For all their romanticising tendencies, Carr’s watercolours have an integrity that lacks in her later paintings of indigenous subjects. Disillusionment at her lack of success and dire financial necessity drove her to abandon painting altogether for an extended period, and her career only resumed when her work was included unexpectedly in a major exhibition of Canadian west coast art. As a result she was thrust into the spotlight and was introduced to American modernist painter Mark Tobey and also the Group of Seven, whose visionary paintings invest the Canadian landscape with an epic, divine presence.

Carr’s exposure to these new influences resulted in an astonishing shift in style; in her large-scale oil paintings from the late 1920s the brushwork is tight and the forms closely defined, while the cropped composition invests the totems with a strangeness and sense of menace absent from her watercolours. In Blunden Harbour, c.1930 (pictured left), the documentary purpose of her earlier paintings has gone. The carved heads and figures are almost fetishised, these unnervingly animated, humanoid figures replacing any human presence, while the surrounding landscape is reduced to an anonymous and largely featureless space. In her clinical observation and studious application of modernist ideas, Carr has lost her empathetic gaze and with it the paintings their integrity.

Carr’s exposure to these new influences resulted in an astonishing shift in style; in her large-scale oil paintings from the late 1920s the brushwork is tight and the forms closely defined, while the cropped composition invests the totems with a strangeness and sense of menace absent from her watercolours. In Blunden Harbour, c.1930 (pictured left), the documentary purpose of her earlier paintings has gone. The carved heads and figures are almost fetishised, these unnervingly animated, humanoid figures replacing any human presence, while the surrounding landscape is reduced to an anonymous and largely featureless space. In her clinical observation and studious application of modernist ideas, Carr has lost her empathetic gaze and with it the paintings their integrity.

When at the end of her career, Carr moved away from representing indigenous art her painting transformed once again, and finally, it seems, we see the real Emily Carr. By concentrating on the landscape she loved, Carr found that her true subject was that amazing sense of life that bursts forth from her tree pictures, and through it she found a new way to honour the indigenous people of British Columbia.

Carr herself said, "Painting is a striving to express life. If there is no movement in the painting, then it is dead paint." Ever resourceful, and due as much to poverty as artistic necessity, she developed a new technique; using white house paint coloured with pigment and thinned with petrol, she was able to paint with fast, vigorous brushstrokes, and her late work shimmers with movement, light and life.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Add comment