Britten 100: Birthday Concert, Union Chapel/A Life in Pictures, National Portrait Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Britten 100: Birthday Concert, Union Chapel/A Life in Pictures, National Portrait Gallery

Britten 100: Birthday Concert, Union Chapel/A Life in Pictures, National Portrait Gallery

Sober choral concert from The Sixteen and a vivacious centenary photographic exhibition

“Translated Daughter, come down and startle/Composing mortals with immortal fire.” So W H Auden invokes heavenly Cecilia, patron saint of music, and it seems she did just that with Benjamin Britten, who set Auden’s text for unaccompanied choir and happened to be born on the saint’s day 100 years ago.

On the day itself, this Hymn to St Cecilia was the one piece that cried out to be heard, so last night I headed up to Islington to hear The Sixteen – in this case The Twenty-Two plus harp and piano - in the atmospheric surroundings of the spooky Union Chapel, commandeered as part of the Barbican Centre's weekend celebrations. It seemed a good idea to pop in along the way on the National Portrait Gallery’s selection of 50 photographs illustrating the composer’s mostly musical life. Glad I did, because the little exhibition lifted the spirits in the way that the concert only intermittently managed.

Did it have to be so dour an occasion? There may have been something bizarrely touching about the fact that the audience and performer demographics were presumably no different from the 1950s, when the prim Choral Dances from the otherwise unconventional coronation opera Gloriana were composed. Yet unrelieved, mostly a cappella choral works by one composer, when we might have had an interlude in the shape of the oboe Six Metamorphoses after Ovid, the guitar Nocturnal after John Dowland or even a song cycle, restricted the palette and the potential for vivacity

So a little warm-up speech would have been welcome, telling us perhaps why the choir was so looking forward to singing this music on the special birthday. Why not announce what the programme advised – which not everyone had time to read beforehand, though I hope they did after, because the notes by theartsdesk's Alexandra Coghlan and the poems were well worth reading – which was not to applaud between the first four pieces, and why not above all give an outline of the diverse threads?

For the biggest problem was the unintelligibility of the texts; probably 80 per cent or more of the words were lost. I don’t know whether this is a cowling effect of the Union Chapel – certainly it’s not over-reverberant – or the Sixteen’s approach to diction (the singers pictured above with conductor Harry Christophers by Molina Visuals). The balladesque A Shepherd’s Carol, second on the programme, was baffling in the extreme, though redeemed in the second half by a ballad proper and one of the two unquestionable masterpieces of the evening, The Ballad of Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard. Here at least, confined to the clearer men’s voices (Britten wrote the piece in 1943 for officers interred in a German concentration camp), we got the gist of infidelity and murder; and the spacious opening bell tolls were masterfully commanded by pianist Christopher Glynn.

Striking, uncredited solos graced the flowing divinity and playfulness of the crucial St Cecilia benediction, and where words were again inaudible, conductor Harry Christophers’ shaping of lines went far towards making amends. Nothing can really make the bulk of the Five Flower Songs or the outer panels of the Gloriana Norwich masque that distinctive: would you guess Britten here? I’d say for the most part not. But there were further glories in the late sequence Sacred and Profane, musically peerless in the climactic vision of Christ on the cross, and a bracing encore in the brilliant meeting of long lines and vocal marching rhythms in Advance Democracy (or perhaps that should be Advance, Democracy), a 1938 agitprop piece transforming doggerel by the Communist Daily Worker editor Randall Swinger. Again, there was a delicious incongruity between the circumstances of the performance and the origin of the setting.

Next page: more on the National Portrait Gallery's selection of Britten photographs

“A Life in Pictures” might have been more pertinently called “Ben and Colleagues”, because the exhibition's curator Robin Francis had the admirable idea of including portraits of fellow musicians and supporters from the NPG’s collection. It was good to see comic bass Owen Brannigan, the first Bottom in Britten's operatic version of A Midsummer Night's Dream, and Cecil Beaton effortlessly glamourising Marion Stein, later Harewood and Thorpe. Perhaps the finest of all is Bill Brandt’s study of Tippett in an industrial setting.

This was one I hadn’t seen, and indeed many of the composer portraits, the majority donated by the Britten Estate in 1981, were unfamiliar. A few appear in Humphrey Carpenter’s still-valid biography, the most affectionate, though not the one pictured right, of baby Ben held by his nanny Annie Walker in 1914). For humorous surprise, nothing can beat the line-up of young participants in a production of The Water Babies, with six and a half year old Ben as Tom on the knee of his mother playing Mrs Do-as-you-would-be-done-by.

This was one I hadn’t seen, and indeed many of the composer portraits, the majority donated by the Britten Estate in 1981, were unfamiliar. A few appear in Humphrey Carpenter’s still-valid biography, the most affectionate, though not the one pictured right, of baby Ben held by his nanny Annie Walker in 1914). For humorous surprise, nothing can beat the line-up of young participants in a production of The Water Babies, with six and a half year old Ben as Tom on the knee of his mother playing Mrs Do-as-you-would-be-done-by.

The double portraits generally see Britten as his most relaxed, especially wandering with E M Forster (picture at top of page by Kurt Hutton/Hubschman) and having tea in the Glyndebourne garden with librettist-to-be Eric Crozier (let’s save that for the review of Albert Herring tomorrow). There are heart-warming shots of Britten and Pears arm in arm with Poulenc as well as with their great Russian friends Mstislav Rostropovich and Galina Vishnevskaya.

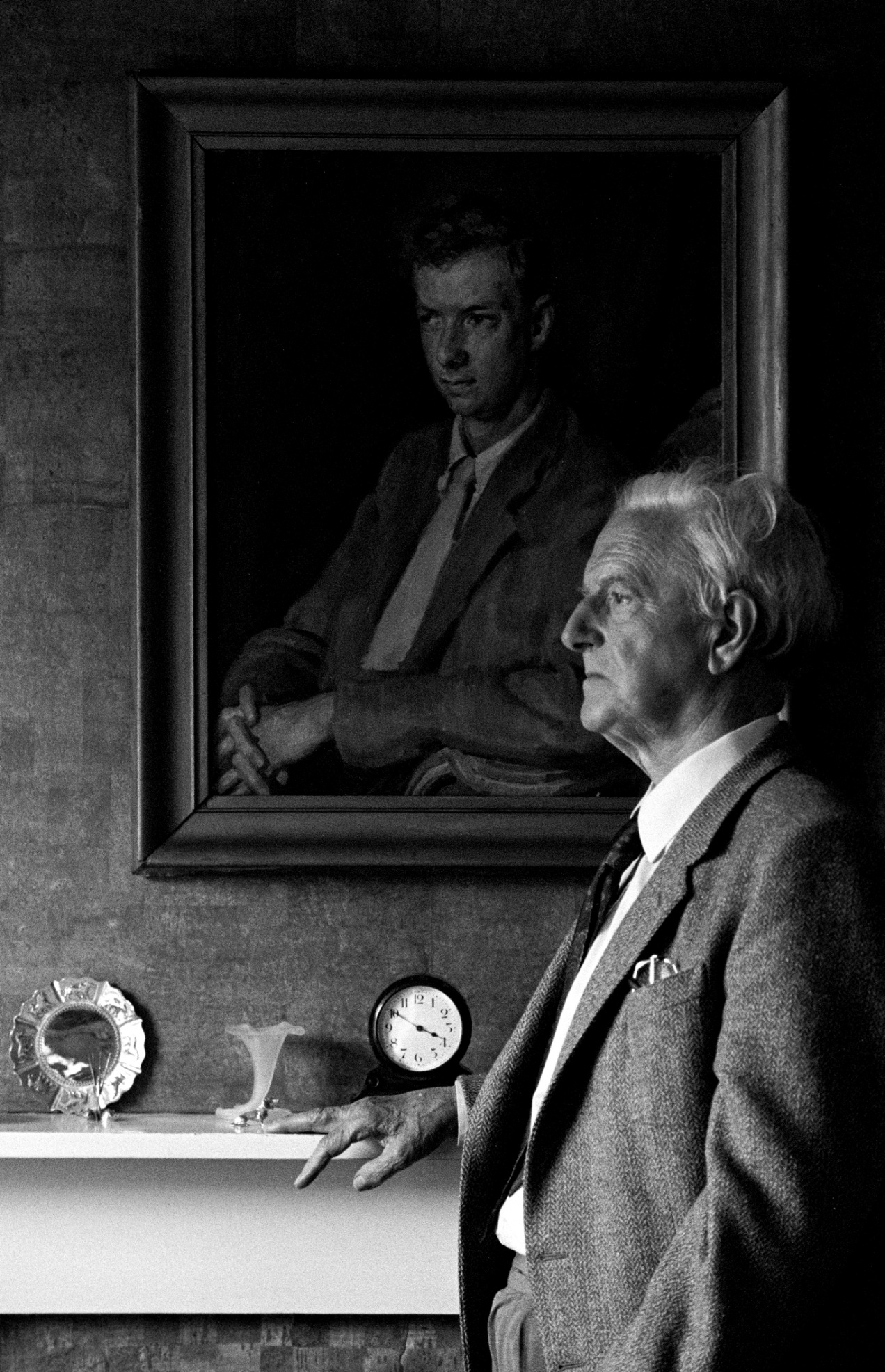

And of course we see a studio representation of Britten and his main man, life and musical partner Peter Pears, to complement the 1943 double-portrait by Kenneth Green in the same gallery, which with plenty of other great paintings by distinguished artists makes a colourful setting for the black-and-white photographs. Appropriately the display cases end with a profile of Peter Pears after Britten’s death, standing by his portrait (by Malcolm Crowthers, pictured left). Interestingly, the exhibition could well continue in the shape of the legacy to pupils and acolytes, so many of them happily still with us. But it has plenty of personality as it is, so best to celebrate what, and who, is there rather than what isn't.

And of course we see a studio representation of Britten and his main man, life and musical partner Peter Pears, to complement the 1943 double-portrait by Kenneth Green in the same gallery, which with plenty of other great paintings by distinguished artists makes a colourful setting for the black-and-white photographs. Appropriately the display cases end with a profile of Peter Pears after Britten’s death, standing by his portrait (by Malcolm Crowthers, pictured left). Interestingly, the exhibition could well continue in the shape of the legacy to pupils and acolytes, so many of them happily still with us. But it has plenty of personality as it is, so best to celebrate what, and who, is there rather than what isn't.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment