The Three Kings review – saluting Busby, Shankly and Stein | reviews, news & interviews

The Three Kings review – saluting Busby, Shankly and Stein

The Three Kings review – saluting Busby, Shankly and Stein

Moving documentary about a trio of Scottish pitmen turned football legends

If Shakespeare had lived in post-war Britain, he surely would have dramatised the careers of the three towering contemporaneous Scottish football managers whose visions of how football should be played and its importance to ordinary people left a greater impact on the nation’s selfhood than any 20th century political leader

Comprised of archival footage newly galvanised in the cutting room, Jonny Owens’ stirring documentary The Three Kings judiciously balances its accounts of the triumphant reigns of Matt Busby at Manchester United (1945–1969), Bill Shankly at Liverpool (1959–74), and Jock Stein at Celtic (1965–78) with the sad stories of their personal declines; “sad” is a better word than “tragic” here since this is a chronicle that incorporates the Munich Airport Disaster, which, on 6 February 1958, claimed the lives of eight of Busby's legendary "Babes" and of 15 others.

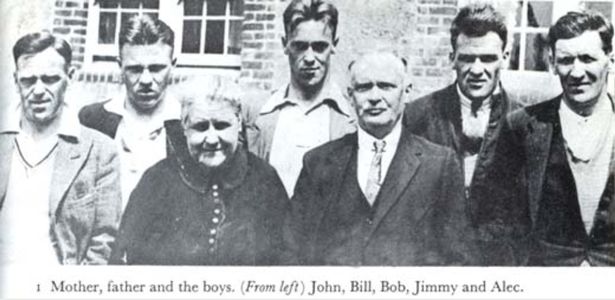

Busby, Shankly, and Stein were born in villages within 30 miles of each other in the Lanarkshire and Ayrshire coalfields and worked in the pits when they were young (Stein until he was 27). (Pictured above: young "Wullie" Shankly, second from left.) While acknowledging that these Scots' experiences of industrial graft and economic deprivation helped shape their powers of nurturance and motivation, The Three Kings doesn’t forge much of a connection between their success and that of Alex Ferguson, born in nearby Govan and mentored by Stein prior to his appointment by United, or mention that Wearsider Bob Paisley, Shankly’s lieutenant and tactician before he succeeded him, had been a miner, too. (Harry Catterick, Shankly and Busby’s high-achieving rival at Everton from 1961 to 1973, also had coal dust in his genes.)

Busby, Shankly, and Stein were born in villages within 30 miles of each other in the Lanarkshire and Ayrshire coalfields and worked in the pits when they were young (Stein until he was 27). (Pictured above: young "Wullie" Shankly, second from left.) While acknowledging that these Scots' experiences of industrial graft and economic deprivation helped shape their powers of nurturance and motivation, The Three Kings doesn’t forge much of a connection between their success and that of Alex Ferguson, born in nearby Govan and mentored by Stein prior to his appointment by United, or mention that Wearsider Bob Paisley, Shankly’s lieutenant and tactician before he succeeded him, had been a miner, too. (Harry Catterick, Shankly and Busby’s high-achieving rival at Everton from 1961 to 1973, also had coal dust in his genes.)

But Owen does convey how football was the lifeblood of the mining communities and how the desire to improve and prove themselves, unattainable goals in the pits, drove Busby, Shankly, and Shankly to create teams to win for the masses. The pugnacious Shankly was the most vocal on this theme, characterizing football as “socialism… playing for each other”. Stein, who publicly kept his cards close to his chest, also urged on his players the need to “help each other”. Busby fostered the self-expressiveness of individual geniuses, so a mantra was born: “Charlton...Law...Best”.

Accompanied by a book written by Owen and Leo Moynihan, The Three Kings is an important release because the sports journalist Hugh McIlvanney’s magnificent three-part Arena documentary The Football Men: Busby, Stein & Shankly (1997) is only available on YouTube. Watched side-by-side, the two films are a study in contrasts. Featuring and narrated by McIlvanney, himself a Kilmarnock miner’s son, The Football Men is sober, old-fashioned, sociologically weighted BBC journalism. (Pictured below: Manchester United line up against Red Star Belgrade on the day before the Munich Airport Disaster.)

The Three Kings relates the managers' destinies and their club’s evolutions to pop culture and political upheavals as it unfolds with the kind of post-2000 Premier League-era panache modern audiences demand. The Merthyr-born Owen is a miner’s son, too – in 2006 he made a film about the 1966 disaster at Aberfan, where his father helped with the recovery efforts. If his film isn't as deep-dyed a slice of working-class social history as The Football Men, it nonetheless emphasizes Busby, Shankly and Stein's empathy for the working folk who worshipped their teams.

The Three Kings relates the managers' destinies and their club’s evolutions to pop culture and political upheavals as it unfolds with the kind of post-2000 Premier League-era panache modern audiences demand. The Merthyr-born Owen is a miner’s son, too – in 2006 he made a film about the 1966 disaster at Aberfan, where his father helped with the recovery efforts. If his film isn't as deep-dyed a slice of working-class social history as The Football Men, it nonetheless emphasizes Busby, Shankly and Stein's empathy for the working folk who worshipped their teams.

One sequence of The Three Kings was disconcertingly edited. The appropriately sombre aftermath of the Munich disaster is preceded by a hectic montage of footage and photos that capture United’s 1957-58 European Cup campaign, including shots of goals being scored, the Brycreemed lads smiling for a camera during training, and pictures of them at airports departing for away ties. The montage is so fast and ends so abruptly, it suggest the momentum of their doomed plane on the runway and its desolation in the Munich snow. If that gives pause, it also reflects a truth: along with the team itself, half a city’s dreams, and the dreams of thousands more, disappeared in a few seconds. Later on, the film excerpts a clip from a BBC interview with the weary 61-year-old Sir Matt – ill-advisedly recalled to the United hot seat in retirement – in which he uses a metaphor for the strain endured by football managers that unintentionally invokes the specter of Munich: “You’re always frightened of the next game. You’re sometimes looking for snow and it’s not falling”.

Whereas McIlvanney’s film has McIlvanney, Owen uses a number of unseen commentators. The Three Kings benefits from the enlightening thoughts of the quietly spoken journalist Richard Williams. He marvels at how Busby, who admitted to being sick for three years after Munich, harnessed the loss of his Babes as a “moral force for regeneration that showed enormous strength of character and singleness of purpose”. Comparing the values Busby and Shankly instilled – United's flair with Liverpool's force – Williams speaks of the fascination of living “through a time when the soul of something is being created and it’s a soul that assumes a kind of permanence.” There were echoes of the Busby Babes in Fergie’s Fledglings. Shankly’s “fantastically well-functioning attacking machine” has been revived in Jürgen Klopp’s high-pressing heavy metal football.

Football authors Patrick Barclay and Archie Macpherson (the Scottish commentator) make telling points, the latter directly attributing Celtic’s 21st century success and affluence to Stein. Karen Gill, the eldest of Shankly’s granddaughters and the author of The Real Bill Shankly, offers poignant insights into how his obsession with Liverpool ate into his family life and how his premature resignation after the team’s 1974 FA Cup Final victory robbed his life of meaning (though he proved himself a more attentive grandparent than he had been a father). (Pictured above: Stein and Shankly at Celtic captain Billy McNeill's 1974 testimonial.)

Football authors Patrick Barclay and Archie Macpherson (the Scottish commentator) make telling points, the latter directly attributing Celtic’s 21st century success and affluence to Stein. Karen Gill, the eldest of Shankly’s granddaughters and the author of The Real Bill Shankly, offers poignant insights into how his obsession with Liverpool ate into his family life and how his premature resignation after the team’s 1974 FA Cup Final victory robbed his life of meaning (though he proved himself a more attentive grandparent than he had been a father). (Pictured above: Stein and Shankly at Celtic captain Billy McNeill's 1974 testimonial.)

Shankly said he felt he had become complacent and decided to retire as a matter of conscience, yet it was an uncharacteristically self-destructive act for a man who needed to die with his boots on. The film doesn’t mention Liverpool’s shoddy treatment of Shankly after his retirement; he wrote in his autobiography that crosstown rivals Everton were more hospitable to him than the club he'd resurrected.

Glasgow’s Catholic side, Celtic had somewhat grudgingly hired Stein, a Protestant, because he was the best available manager in Scotland in 1965. He swept all before him in the following decade, as early as 1967 becoming the first manager of a British club to win the European Cup, pipping United to the post by a year. The former Celtic board member James Farrell praises Stein’s intelligence, directness, and ability to handle people. Macpherson believes, however, that Stein felt there were Catholics at the club who still resented him. Pressured to resign when Celtic were in a slump, he invited McNeill to replace him. Unlike Shankly, Stein was offered a job on his club’s board – to sell pools tickets. Instead, he managed Leeds United for 44 days (as, precisely, did Brian Clough), then became manager of Scotland.

Stein did die with his boots on, suffering a fatal heart attack two minutes before the end of a 1985 World Cup qualifier against Wales that ended with a crucial draw after he’d brought on the substitute, Davie Cooper, who secured it with an 81st minute penalty. To maintain focus, Stein had left off his heart medication before the game. The Three Kings’ shows upsetting footage and photos of him, pale and perspiring, sitting next to Ferguson on the Scotland bench and being carried away to receive treatment. Ferguson recalls finding Graeme Souness, in tears, outside the Ninian Park medical room. "I think the Big Man's gone," Souness told him. The image of the ultimate Scottish hard man welling up is chastening – and indicative of the affection Stein inspired in his players. (Pictured below: Busby and Bobby Charlton embrace after Manchester United's 1968 European Cup Final win.)

The Three Kings arrives on screens at a moment when, because of social distancing, the footage of vast crowds celebrating trophy-winning exploits in the stadiums and on the streets of Manchester, Liverpool, and Glasgow seems fantastical. The communal experience of football underpinned the achievements of these three great men, as Stein acknowledged when he said, “If you play a football match without fans, you’ve got nothing.” Crowdless football is the only sane option right now, but not until vaccines allow the people to return will it reacquire some of the purpose and power it had when Busby, Shankly, and Stein were making them sing.

The Three Kings arrives on screens at a moment when, because of social distancing, the footage of vast crowds celebrating trophy-winning exploits in the stadiums and on the streets of Manchester, Liverpool, and Glasgow seems fantastical. The communal experience of football underpinned the achievements of these three great men, as Stein acknowledged when he said, “If you play a football match without fans, you’ve got nothing.” Crowdless football is the only sane option right now, but not until vaccines allow the people to return will it reacquire some of the purpose and power it had when Busby, Shankly, and Stein were making them sing.

- More film reviews on theartsdesk

- The Three Kings is in cinemas from 1 November

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Add comment