Mayerling, The Royal Ballet/ Le Jeune Homme et La Mort, English National Ballet | reviews, news & interviews

Mayerling, The Royal Ballet/ Le Jeune Homme et La Mort, English National Ballet

Mayerling, The Royal Ballet/ Le Jeune Homme et La Mort, English National Ballet

MacMillan's historical drama draws out the best in the Royal Ballet's actors

The acting tradition is refined in British ballet to a height not matched anywhere else in the world - distilled in Frederick Ashton’s ballets, expanded in Kenneth MacMillan’s.

There isn’t a more demanding role than Crown Prince Rudolf in Mayerling, a ballet that bucks all the rules. MacMillan’s last and greatest narrative ballet - now 35 years old - is epic and unexpected in every way. Its leading character is no hero but a damaged beast of an inbred aristocrat, surrounded by large numbers of manipulative characters. The milieu is high politics, the trade is power for sex, and the resolution is vile, a murder-suicide pact. Noble or redemptive it is not, and it takes a scene or two to work out who is who.

But MacMillan brushes aside the risk of getting lost, unfolding and choreographing this story so ambitiously that it provides dancers with the most complex roles anywhere to be found, and an audience with a daring trip out of comfort to the imagining of utmost agonies in a young man’s mind.

That is, if the dancers can rise to the difficult occasion. Which is emphatically what Edward Watson and the cast for the first night of the return of this major ballet to repertoire at Covent Garden did.

Watson’s incarnation of the wrecked human being who is heir to the Hapsburgs began years ago, with this performer’s instinctive sympathy for outsiders and the courage of an unusually brave artist. His Rudolf, pale, ginger, etiolated, is magnetically flawed - you imagine a boy kept in the dark with too many ancestors’ bones. He compels sympathy, just, through the sheer intensity of the bewilderment and sense of identity loss that seeps through his Rudolf.

Watson’s incarnation of the wrecked human being who is heir to the Hapsburgs began years ago, with this performer’s instinctive sympathy for outsiders and the courage of an unusually brave artist. His Rudolf, pale, ginger, etiolated, is magnetically flawed - you imagine a boy kept in the dark with too many ancestors’ bones. He compels sympathy, just, through the sheer intensity of the bewilderment and sense of identity loss that seeps through his Rudolf.

The court, borne on a tidal wave of rich, romantic, declamatory Liszt, dressed sumptuously by the great Nicholas Georgiadis in late 19th-century bustles and uniforms in deathly colours - charcoal, dried-blood, dirty gold - pullulates with secrets. These are cleverly uncovered in the opening court parade and waltz, celebrating Rudolf’s betrothal to another dynastic royal - his mistress reveals herself, a young girl who will help him die in ghastly circumstances is spotlit, his mother the Empress betrays her deep unhappiness. In a sequence of scenes that sweep the story on with absolute psychological credibility, a domino chain of emotional dislocation topples down right down through the court. No one loves honestly and openly, and Rudolf is the ultimate result, warped.

This material would test fine straight theatre actors, but for dancers even more so, especially given the huge dancing demands in Rudolf’s role, with a shattering series of pas de deux with different women, and three exceedingly testing solos. The calibre of the challenge has drawn into the Royal Ballet wonderfully gifted men, such as Irek Mukhamedov and Johan Kobborg (and we must count the Royal Ballet runaway Sergei Polunin, I think, whose Mayerling in Moscow this spring was by every account superb).

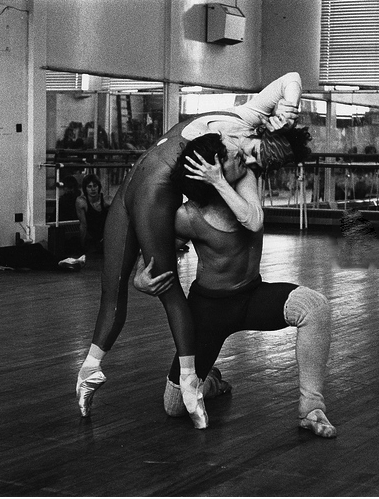

Watson, 36, is among the gods in this part, layered, vivid, self-loathing. He has a brilliantly complicit partner as his lover-in-death Marie Vetsera, Mara Galeazzi, who invests the needy acrobatics with an equally susceptible emptiness. There’s a frightening understanding between these two dancers as they coil their bodies around each other - for instance, they use dead weight very remarkably in the pas de deux, not erotically, but as if sharing secrets (pictured left together).

Watson, 36, is among the gods in this part, layered, vivid, self-loathing. He has a brilliantly complicit partner as his lover-in-death Marie Vetsera, Mara Galeazzi, who invests the needy acrobatics with an equally susceptible emptiness. There’s a frightening understanding between these two dancers as they coil their bodies around each other - for instance, they use dead weight very remarkably in the pas de deux, not erotically, but as if sharing secrets (pictured left together).

But other superbly touching interpretations were everywhere: in key position the agonisingly sad Empress Elizabeth of Zenaida Yanowsky - you could see her son in her - and the plangency of Sarah Lamb’s Countess Larisch, the infatuated woman who could be blamed for Rudolf’s downfall, who helps him hide his drugs and who introduces him to the girl who is willing to die with him.

It’s typical of the Royal Ballet in this ballet above all that you clock the individuality and status in the drama of other characters, Gary Avis charming as Bay Middleton, Laura Morera alluring as the courtesan Mitzi Caspar, Ricardo Cervera's Bratfisch. Yes, for sure there are (as with many great operas too) awkward bits of narrative, but every moment is boldly attempted with imagination and thought, and the drive to doom feels inevitable.

It’s typical of the Royal Ballet in this ballet above all that you clock the individuality and status in the drama of other characters, Gary Avis charming as Bay Middleton, Laura Morera alluring as the courtesan Mitzi Caspar, Ricardo Cervera's Bratfisch. Yes, for sure there are (as with many great operas too) awkward bits of narrative, but every moment is boldly attempted with imagination and thought, and the drive to doom feels inevitable.

Regrets are going be poured throughout this Mayerling run, as a generation of tremendous MacMillan dancer-actors prepare their final performances in this pinnacle of his narrative work (pictured right the 1978 Rudolf and Vetsera, Lynn Seymour and David Wall, © Roy Round/ROH - see video below).

Galeazzi and Leanne Benjamin will both give their final shows playing Marie Vetsera before retiring, one fears Johan Kobborg and Carlos Acosta may not be seen again as Rudolf after their scheduled dates. The magical Tamara Rojo, another supreme MacMillanite, has departed to run English National Ballet. These are enormous shoes for others to fill, and the exciting recruitment of Natalia Osipova next season can’t stem fears for how masterworks like Mayerling and Ashton’s subtle character ballets (Month in the Country, Enigma Variations, Marguerite and Armand) will fare.

Perhaps the ultimate Rudolf there might have been, Nicolas Le Riche from Paris

Meanwhile, at the Coliseum this week English National Ballet has been presenting as a guest star perhaps the ultimate Rudolf there might have been, Nicolas Le Riche from Paris Opera Ballet. Le jeune homme et la mort means, of course, the young man and death, and could describe Mayerling. Le Riche's performances of Roland Petit's work have been overwhelming experiences of a man in breakdown, possessed by a death fantasy, magnifying this 17-minute ballet into a kind of theatrical masterwork.

But a strong alternative cast came from the former Royal Ballet principal Ivan Putrov, replacing Yonah Acosta, who had visa trouble. Putrov, 33, who quit Covent Garden two years before Polunin did, looked fit and hungry, despite his recent freelance career, and his portrayal of angry, vulnerable bewilderment in this role was a clue to a still untapped potential for quality performance. As Mae West almost said, a good man is hard to find. Next season might bring surprises at both companies.

- The Royal Ballet performs Mayerling at the Royal Opera House, London, in repertoire till 15 June, with this cast on 1 and 13 June

Watch Viviana Durante's Vetsera visit Irek Mukhamedov's Rudolf in his bedroom in the 1994 Royal Ballet film

Watch a short Royal Opera House film about Watson's preparations for Mayerling

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Vollmond, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch + Terrain Boris Charmatz, Sadler's Wells review - clunkily-named company shows its lighter side

A new generation of dancers brings zest, humour and playfulness to late Bausch

Vollmond, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch + Terrain Boris Charmatz, Sadler's Wells review - clunkily-named company shows its lighter side

A new generation of dancers brings zest, humour and playfulness to late Bausch

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

Comments

I enjoyed this review