Bauhaus: Art as Life, Barbican | reviews, news & interviews

Bauhaus: Art as Life, Barbican

Bauhaus: Art as Life, Barbican

A show focusing on life and work in the famous German art school concentrates on process as well as product

As an art school the Bauhaus has a reputation for being the cradle of modernism, famous for establishing an alliance between art and industry which produced enduring design classics such as Marcel Breuer’s tubular steel chairs, Josef Albers’ silver and glass fruit bowl and Marianne Brandt’s elegant globe lamps. But that is only part of the story.

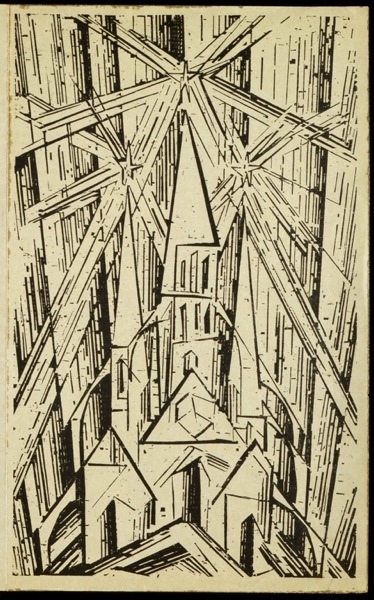

When the school was set up in Weimar in 1919 the image used to embody its aims and ideals owed nothing to new technology. Illustrating the prospectus was a woodcut by Lyonel Feininger (pictured below right) intended to evoke the era of great cathedral building, when artists and craftsmen worked together to produce a gesamtkunstwerk – a total work of art.

“Let us desire, conceive and create the new structure of the future,” wrote Feininger, “which will embrace architecture and sculpture and painting in one unity and which will one day rise toward heaven from the hands of a million workers like the crystal symbol of a new faith.”

“Let us desire, conceive and create the new structure of the future,” wrote Feininger, “which will embrace architecture and sculpture and painting in one unity and which will one day rise toward heaven from the hands of a million workers like the crystal symbol of a new faith.”

Faith played an important role in the heady brew of ideas informing the curriculum. The preliminary course was run by Johannes Itten who, with his shaved head and loose robes, looked like a monk. He promoted Mazdaznan, an eclectic mix of Christian and Hindu beliefs, and imposed on the students a regime of vegetarianism accompanied by fasting and body purges. Before classes, they did gymnastics and breathing exercises to put them in touch with their feelings (pictured below: Sport at the Bauhaus by T. Lux Feininger).

After his course, students elected to go into one of the workshops specialising in stone and wood carving, pottery, weaving, printmaking, bookbinding, wall painting or stage production. There was no architecture workshop but when, in 1920, the director, Walter Gropius was commissioned to design a house for Adolf Sommerfeld, students were invited to contribute. The result is a far cry from the modernist designs associated with the Bauhaus. Inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright, the wooden building looks like a set for an expressionist movie.

When things got too airy fairy, Gropius replaced Itten with the Hungarian László Moholy-Nagy and shifted the emphasis away from arts and crafts towards art and industry, outlining the new approach in a lecture titled Art and Technology, a New Unity. Moholy-Nagy was soon joined by Josef Albers and between them they restructured the preliminary course, introducing open-ended projects that encouraged lateral thinking and were incredibly popular. A typical project required students to devise a stable, free-standing structure from a single sheet of paper without using glue. Tasks like these, which forced them to think afresh about traditional materials and gave them first-hand experience of balance and structure, were as useful to an engineer as a furniture designer or a painter.

When things got too airy fairy, Gropius replaced Itten with the Hungarian László Moholy-Nagy and shifted the emphasis away from arts and crafts towards art and industry, outlining the new approach in a lecture titled Art and Technology, a New Unity. Moholy-Nagy was soon joined by Josef Albers and between them they restructured the preliminary course, introducing open-ended projects that encouraged lateral thinking and were incredibly popular. A typical project required students to devise a stable, free-standing structure from a single sheet of paper without using glue. Tasks like these, which forced them to think afresh about traditional materials and gave them first-hand experience of balance and structure, were as useful to an engineer as a furniture designer or a painter.

When, in 1924, state funding was cut, the school moved to the industrial town of Dessau and began developing relationships with local manufacturers. The new building designed by Gropius provided student accommodation as well as studios, workshops, a canteen and theatre; Gropius also designed houses for the teachers including Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee and Oskar Schlemmer. This was the period when staff and students not only produced some of the most famous and enduring designs of the 20th century, but also forged a vibrant community that knew how to play as well as to work.

Bauhaus: Art as Life focuses on the Bauhaus both as an art school and a community. Some of those famous designs, in which simple geometry leads to elegant and effective solutions, inevitably are included. Albers’ fruit bowl consists of a shallow, silver-plated rim held in place above a circle of glass by three wooden spheres. Mies van der Rohe’s table is a circle over a square; the circular glass top rests on tubular steel rods bent to delineate a cube. Meanwhile Anni Albers and Gunta Stölzl, the only woman entrusted with a workshop, were producing abstract wall hangings and textiles to die for (pictured right: wall hanging by Gunta Stölzl).

Bauhaus: Art as Life focuses on the Bauhaus both as an art school and a community. Some of those famous designs, in which simple geometry leads to elegant and effective solutions, inevitably are included. Albers’ fruit bowl consists of a shallow, silver-plated rim held in place above a circle of glass by three wooden spheres. Mies van der Rohe’s table is a circle over a square; the circular glass top rests on tubular steel rods bent to delineate a cube. Meanwhile Anni Albers and Gunta Stölzl, the only woman entrusted with a workshop, were producing abstract wall hangings and textiles to die for (pictured right: wall hanging by Gunta Stölzl).

More interesting than the familiar products, though, are the many experiments in colour, form, balance and so on produced by the students in various classes. Yet despite the show’s alleged focus on the Bauhaus as a school, precious little information is given about the sophisticated theories developed by the tutors, all of whom were artists in their own right.

No mention is made of the incredibly detailed notes made by Paul Klee for the lectures he gave between 1921-31 and published by the Bauhaus as the Pedagogical Sketchbook, nor of Kandinsky’s analysis of the dynamics of pictorial space published as Point and Line to Plane nor Johannes Itten’s amazingly comprehensive colour theories published later as The Art of Colour. (pictured below: Circles in a Circle by Wassily Kandinsky)

A lot is made of the importance of play at the school, but there’s scarcely any mention of Oskar Schlemmer’s role as head of the theatre workshop, which orchestrated festivities such as the famous fancy dress parties, or the influential courses he taught on the human body and its relationship to the environment. Three costumes for his famous Triadic Ballet (1922) are included, but there are no film clips to bring them and his other radical costume designs to life.

With so little detail provided about the courses run by key members of staff, the things made by students in response to them begin to feel arbitrary – more like random experiments than explorations of specific concepts. The catalogue may, of course, elucidate some of these ideas, but the gallery was not giving any out and I declined to spend half the night reading pages on screen or printing them off.

With so little detail provided about the courses run by key members of staff, the things made by students in response to them begin to feel arbitrary – more like random experiments than explorations of specific concepts. The catalogue may, of course, elucidate some of these ideas, but the gallery was not giving any out and I declined to spend half the night reading pages on screen or printing them off.

The Barbican claims that this is the largest Bauhaus exhibition to be held here in over 40 years; this may be true, but I haven’t forgotten the far more dynamic Modernism: Designing a New World staged at the V&A in 2006, which presented Bauhaus achievements in the context of the ideas that inspired modernists everywhere, an approach that ultimately made for a more intelligible and engaging experience.

- Bauhaus: Art as Life at the Barbican until 12 August

rating

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Comments

A very good review. Much more