theartsdesk Q&A: Choreographer Christopher Wheeldon | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Choreographer Christopher Wheeldon

theartsdesk Q&A: Choreographer Christopher Wheeldon

How the Royal Ballet extravaganza Alice's Adventures in Wonderland was brought to the screen

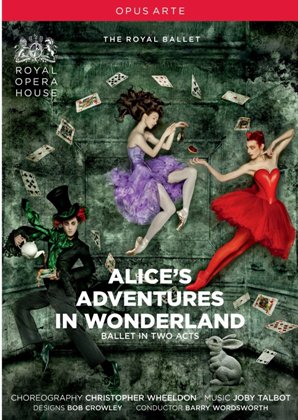

Those of us un-Zeitgeisty enough to miss the Royal Ballet’s first new full-length ballet in 20 years during its first run can now catch up. Opus Arte’s DVD release of the televised Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland tells a different story from the one any audience members other than front-of-stalls ticket holders would have caught. With more focus on the characters and less on the potentially overwhelming special effects, we probably get a better deal.

Jonathan Haswell’s stylish screen direction is dominated, as it should be, by the loveable mug of Lauren Cuthbertson's Alice. She guides us in glorious close-up through the Carroll labyrinth according to choreographer Christopher Wheeldon, composer Joby Talbot and Nicholas Wright, deviser of a better scenario than countless garbled, overstuffed versions of the Wonderland experience.

So when I finally spoke to Wheeldon, not yet 40 and recently announced part of the Royal Ballet’s starry choreographic team headed by Kevin O’Hare, I was able to enthuse quite sincerely, as many of my colleagues had not – a helpful starting point which he took very graciously before summing up the pros and cons.

DAVID NICE: I’ve enjoyed reading everything you had to say about the new ballet leading up to the premiere; the difference is of course that this is after, and now you’ve also seen the film. Were you pleased with the end results and would you change anything?

DAVID NICE: I’ve enjoyed reading everything you had to say about the new ballet leading up to the premiere; the difference is of course that this is after, and now you’ve also seen the film. Were you pleased with the end results and would you change anything?

CHRISTOPHER WHEELDON: Well, I think a big production like Alice in Wonderland is inevitably going to be a bit of a work-in-progress for a while, if not for ever, because there’s so much in it and as time passes there will be things that I’ll probably go in and tweak a bit. But I think that I’m very pleased with the way that it’s turned out as a production over all - it feels whole and seems to work well. Never say never, I probably will go in and make some tweaks, but that’s not going to happen for a while.

It’s scheduled for revival in March 2012 and will probably come back every season for the foreseeable future, don’t you think?

I think the hope is that it will eventually take its place in the repertoire as a Christmas or a holiday ballet of some sort, so yes, I’m sure they’ll probably roll it out once in a while.

Let’s talk about the structure of it, which came in for some criticism but seems to make sense to me in the film: the fact that in the first act you deal with a sequence of fluid scenes and then in the second it tightens up, that seems pretty perfect to me – was that something you conceived from the start? Was it purely through working with Joby Talbot and your scenarist Nick Wright?

Yes, it was – we really wanted to make sure that the ballet came together dramaturgically in the last act. The book itself is very episodic and that’s why we decided to create this second narrative and to give Alice a purpose going through Wonderland following the Knave of Hearts and setting up that little relationship at the beginning [the Liddells are seen in Oxford, where a little scene develops with the gardener’s boy who will metamorphose into the Knave (Lauren Cuthbertson pictured with Sergei Polunin)]. And that trial sequence at the end, it’s completely mad in the book and our concern came from the observation that on stage historically Alice hasn’t worked very well, and part of the reason why it hasn’t worked very well is that there’s never been a satisfying conclusion or for that matter a satisfying journey for Alice through Wonderland – on the page it feels like a lot of little episodes full of wordplay and crazy characters.

Yes, it was – we really wanted to make sure that the ballet came together dramaturgically in the last act. The book itself is very episodic and that’s why we decided to create this second narrative and to give Alice a purpose going through Wonderland following the Knave of Hearts and setting up that little relationship at the beginning [the Liddells are seen in Oxford, where a little scene develops with the gardener’s boy who will metamorphose into the Knave (Lauren Cuthbertson pictured with Sergei Polunin)]. And that trial sequence at the end, it’s completely mad in the book and our concern came from the observation that on stage historically Alice hasn’t worked very well, and part of the reason why it hasn’t worked very well is that there’s never been a satisfying conclusion or for that matter a satisfying journey for Alice through Wonderland – on the page it feels like a lot of little episodes full of wordplay and crazy characters.

And the wordplay’s the very first thing to go, isn’t it?

The wordplay is of course the very first thing to go, and that’s a large chunk of the charm of the original Lewis Carroll novel. So we needed a glue to pull all of those episodes together, and it is a journey, that first scene, so she has to be introduced to all the characters in order for them to come together in the second act, in order to help bring the story to a conclusion. It did naturally take that kind of structure.

It strikes me that the wonderful sequence in the court room where everybody gets their little reprise is like a big Fokine number, isn’t it, with the ensemble where everyone is marked out by their musics and they all do their bits. It comes together as a finale and you don’t have to force it, because that’s actually in Carroll, isn’t it – the Mad Hatter and the Duchess do come back.

It is there, yes, and what we decided to do was to pull all of the characters into the trial – the Caterpillar’s not there in the original, for instance, and the Dormouse and March Hare aren’t involved, but that scene did give us almost a traditional classical ballet third act, only in the second, where everybody comes to the ball and dances a little solo. But what we did want to do was to continue the narrative through that rather than just make it a sequence of variations that start and finish and then everyone applauds. This gave the characters an opportunity to continue the storytelling and have their 11 o'clock number, as it were.

The characters in Wonderland are all beautifully drawn in the book and lend themselves very well to dance

The idea of concentrating on the first Lewis Carroll book, I find that refreshing. Obviously you can’t include every episode in Alice, but the temptation is to chuck in characters from Through the Looking Glass: isn’t that how Disney went wrong, and Tim Burton too? And I hear Ashley Page [in the Scottish Ballet production] has brought in other characters. That makes it too unwieldy, doesn’t it?

Well, there are plenty of characters already in Wonderland, and they’re all beautifully drawn in the book, and lend themselves very well to dance. We spent a lot of time deciding who to leave out, we didn’t want to bring anyone else in, they’re all beloved characters and it didn’t seem necessary to bring in more, and even with the characters we included we still ended up with a substantial first act, which may end up being one of the alterations that’s made in the future, tailoring that down a little bit. But yes, we didn’t see any reason to bring in any characters from Through the Looking Glass.

It must have been hard enough to leave out the Gryphon and Mock Turtle.

Yes, it was, and also the only real dance in Alice in Wonderland the book is the Lobster Quadrille. But we just felt that would have been one scene too many.

Their scene crops up as an interlude, perhaps, just when you want to knit it all together.

We would have ended up with another episode in Act II [dominated by Zenaida Yanowsky's Queen of Hearts (pictured right)], and it didn’t quite fit, you’re right.

We would have ended up with another episode in Act II [dominated by Zenaida Yanowsky's Queen of Hearts (pictured right)], and it didn’t quite fit, you’re right.

Did you have Joby Talbot’s music in mind from the start? I’m curious to know at what point he arrived at the idea of this incredible rhythmic ticking and the sense of time passing, the strangeness which gives the overall colour to the piece – did that come in later?

Well, I asked Joby to write the music and he thankfully had a big commission that had just fallen through – not so good for him but great for me - and he took it on board immediately. And he must have written about the first six or seven minutes and presented it to me and immediately it clicked. We’d talked about the underlying themes of Alice, the White Rabbit with his stopwatch, the sense of always trying to get somewhere and never quite getting there. And the dark strangeness of the tale and the make-believe fantasy world of Carroll’s storytelling to the girls; all of these elements found their way into that first kind of sound-sketch he made. It felt absolutely perfect the instant he played it to me. I remember thinking, this is it, this is the world of Alice, so from there on it was full steam ahead.

And I suppose when you heard it orchestrated that was an extra kick, with all the percussion?

Yeah, and the good thing is that nowadays you can simulate orchestration on the computer quite well – it’s a much more realistic sound, so I had an idea of how it was going to sound, but of course there’s nothing quite like the first time an orchestra sits down and plays a new piece, that’s one of the magical moments that an audience never gets. It gets the finished product, but the excitement of actually putting together all of those elements piece by piece and hearing them come together, that’s very exciting.

…By which stage most things have already been decided, at least for the first run, it’s only later you can change what you want as a result of what you hear. Did you give Joby Talbot specifications like Petipa did for Tchaikovsky, 32 bars here for variation and so on?

Oh yes, not going quite so far as how many bars, but we made a very strict time structure for how long the Mad Hatter’s scene should be, how long the Caterpillar's. Then those little incidental things like how long should Alice fall down the rabbit hole, which is where you have to bring the designer in, because we had to come up with a concept of how she’s going to fall, and then you’ll know whether that’s a musical sequence that can go on a little bit longer, because it’s going to be visually interesting, or whether you want it over in a matter of 20 or 30 seconds. So that was very much back and forth, at first between Nick, Joby and myself, and then we brought Bob [Crowley, the designer] into the equation as well. Because there are a lot of transitions in that first act leading through and seamless kind of discoveries of new parts of Wonderland, and that has to be taken into consideration as well: how long does it take for a scrim to fly out and for Alice to pass through? It’s a complex equation when you look at it.

What I saw was not what I expected, to be honest; the effects are in perfect balance with the narrative and the characterisation. Did you feel there was a good balance at the end?

Oh yes, absolutely, and you know it’s very big-looking as a show and there are a lot of effects. But we wanted to find ways to create those effects that were suitably theatrical and almost old-fashioned in a way. By using puppetry and by taking something as modern as the really wonderful animation and projection that you can now use in theatre and combining that with old-fashioned techniques and trying as far as possible to keep all those things integrated, we wanted the audience to have the impression that it was never just watching a piece of film – that it was watching something that takes a lot of human craft as well as computerised imagery, and combining those to make pure theatre in a tradition.

Absolutely, and I suppose if video projection had been around in Tchaikovsky’s time he would have loved the idea of using it, say, for the Panorama in The Sleeping Beauty (pictured left in Maria Bjornson's designs for the most unjustly ill-fated of the Royal Ballet Sleeping Beauties). Because that scene with the White Rabbit and Alice going through the forest is a Panorama moment, isn’t it?

Absolutely, and I suppose if video projection had been around in Tchaikovsky’s time he would have loved the idea of using it, say, for the Panorama in The Sleeping Beauty (pictured left in Maria Bjornson's designs for the most unjustly ill-fated of the Royal Ballet Sleeping Beauties). Because that scene with the White Rabbit and Alice going through the forest is a Panorama moment, isn’t it?

And it’s an hommage, very much, nobody seems to pick up on that, I’m glad you did. To Petipa and Tchaikovsky…

In old-fashioned theatre you would have had the set rolling…

The scrolling backdrops… exactly.

The reference to The Sleeping Beauty’s Rose Adagio is clear in both the choreography and the music…

Yes, we were scared of that, but we thought it was a fun idea.

It arrives at just the right time.

Well, the Queen [a dream parody of Alice’s difficult mother; both played in the film by Zenaida Yanowsky] needs a big number to introduce her in the second act. We thought, wouldn’t it be funny if deep down all this hard-nosed angry woman actually dreams of is being a ballerina, a 16-year-old Princess Aurora type, and once she gets in front of a crowd she can’t help herself? So that’s how the diva-ballerina aspect came about, and I remember saying, "Let’s just rip off the Rose Adagio."

It has to be a grand moment but a funny grand moment, doesn’t it?

It's dangerous making fun of the Rose Adagio at the Royal Ballet where it’s been the mothership for so many years, but at the same time we do it from a place of love, so I think it comes across.

And Zenaida Yanowsky with the fabulous fixed smile of the ballerina – she’s consummate, isn’t she?

It’s wonderful – I’ve only seen the recording of the second performance, I haven’t seen the edited version, but it’s nice to be able to go in on faces, I really enjoy that about the recording, because of course at Covent Garden unless you’re in the front 10 rows of the stalls you never really get the expressions.

And that allows you to focus more on Lauren Cuthbertson (pictured right in rehearsal with Edward Watson), whose facial expressions are so appealing.

And that allows you to focus more on Lauren Cuthbertson (pictured right in rehearsal with Edward Watson), whose facial expressions are so appealing.

She’s really remarkable, a very special actress. I think it’s been a long time since there’s been a British dance actress of her calibre. She was such great fun to work with.

You created that particular role with her in mind?

Yes, I did. Unfortunately she was ill for the first six months of the creative process – luckily I was only going in and out for a week here and there from New York, and by the time I came in late summer to start rehearsals for real, she was better.

And was it the same with Edward Watson’s White Rabbit and Steven McRae’s Mad Hatter – did you create those roles around their particular characters?

Yes, they were all created with those characters specifically in mind. I think initially people were a little surprised that I didn’t reverse their casting and have Steven as the White Rabbit and Edward as the Mad Hatter.

Perhaps they associated the Mad Hatter with the neurosis Edward Watson can convey.

Exactly, and Ed’s so brilliant at subtly conveying the, as you say, neurotic and darker traits of human nature from his very big successes in the MacMillan ballets.

The Mayerling is astonishing, isn’t it?

Really amazing, yes. But also physically Edward is a creature, so all of those elements contributed to the White Rabbit’s slightly belligerent but ultimately very warm character – but I really did want to avoid the fluffy white cute bunny syndrome. And then of course I’d known that Steven (pictured left) was a champion tapper for a long time, and it just seemed like a lot of fun to be able to show everybody what he could do out of his ballet shoes and into his tap shoes.

Really amazing, yes. But also physically Edward is a creature, so all of those elements contributed to the White Rabbit’s slightly belligerent but ultimately very warm character – but I really did want to avoid the fluffy white cute bunny syndrome. And then of course I’d known that Steven (pictured left) was a champion tapper for a long time, and it just seemed like a lot of fun to be able to show everybody what he could do out of his ballet shoes and into his tap shoes.

The connection between the tale and the framework was worked out by you together with Nick Wright: it seems to work, particularly the ending with the idea of moving forward in time to the last scene.

That was quite a last-minute brainwave, I have to say, and I’m glad we went for it, because for me it just subtly brings the story to us now, and it is still a classic. I don’t think unfortunately it’s as read by as many children now as when I was growing up, we’ve sort of moved almost away from the classic fairy stories, and kids are much more now into what are becoming the new classics, the Harry Potter stories, and those kind of books. But it is still a beloved book in the UK, and just to be able to wink at the fact that it’s still around, it should be read and it’s a part of our culture today: that I think worked very well.

You were going to need a light touch at the end, which is where I got nervous, and it did work.

We went through a lot of incarnations of that final scene, including Alice waking up and the Knave being there as he was, and her explaining the story, and at the end off they go, and the house revealing all the characters peeping out through the window, and something didn’t feel quite right about that. We had one version where the White Rabbit, still as the White Rabbit, came out and peered over the gate as they disappeared, and in the end actually the cleanest and simplest and I think most touching way was to bring it back round to the idea of Lewis Carroll as a photographer, touching on his character in the first scene but making him someone else, and finally having him discover the book, because the book is where it all begins, and sitting down and starting to leaf through it. We tried it and it just seemed very natural and very comfortable and so it stuck.

Having a really great actor like Simon Russell Beale in the room gave the dancers the opportunity to see how he created this role without words

I think it was courageous not to go with the conventional Freudianisation of the whole Lewis Carroll-Alice Liddell dynamic, which is there to be explored in biographies but not in a ballet. That was the obvious thing to do and you didn’t do it.

Well, we seem to relish dragging our literary heroes of children’s stories through the mire – JM Barrie as well as Lewis Carroll - and it’s kind of a little boring now I think. Why not celebrate these stories as the great stories that they are, and as the important childhood influences that have been a big part of our lives?

But you make some elements quite threatening – the scene in the Duchess’s kitchen has its cook-with-meat-cleaver moment, which links with the execution element later. The music is strident and quite scary.

All good fairy tales are a little bit scary, we love to be frightened as children, and with horror movies throughout our lives. There are very dark moments in Alice, you can’t deny that, and it’s quite possible that they are meant to be more than they seem on the page, yes, so we decided all of those fantastical and dark elements needed to be in the story, but we didn’t want to push it too hard.

I was so pleased you kept in the Pool of Tears and the Caucus Race, because that’s quite difficult to solve on stage, but the wonderful image of the crying eye works well, and I like the Prokofiev-style dance music Joby Talbot writes at that point.

Funnily enough that was the only scene he was slightly resistant about. I said I really think the Caucus Race needs to be a polka, and quite a traditional polka, but zany, I’d like to play around with it being a polka. And it’s one of the few big ensemble numbers in Act I, so it needs to be a big dance with the button as prize at the end. Joby said that the polka wasn’t a musical number he felt comfortable with, but he went away and I think he’s written a really strong piece. I remember at the first orchestral reading how delighted everyone was with the Caucus Race.

You didn’t go for easy options in some of the narration.

It’s tricky really because storytelling-wise, a lot of the things that we chose to include and omit also revolved around whether we thought we could convincingly create those stage effects, like Alice’s growing and shrinking. Unfortunately on the film you don’t really get the growing and shrinking, because there was a projection on a black curtain so that when she first drinks the bottle and shrinks, all the way across these black curtains are projections of the doors that change in size as she does that circular manege. The slightly surreal aspect of the way Bob designed those scenes helped us a lot.

It’s tricky really because storytelling-wise, a lot of the things that we chose to include and omit also revolved around whether we thought we could convincingly create those stage effects, like Alice’s growing and shrinking. Unfortunately on the film you don’t really get the growing and shrinking, because there was a projection on a black curtain so that when she first drinks the bottle and shrinks, all the way across these black curtains are projections of the doors that change in size as she does that circular manege. The slightly surreal aspect of the way Bob designed those scenes helped us a lot.

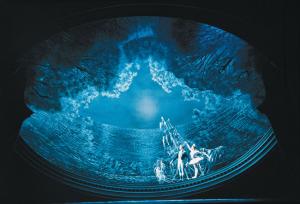

The fantastical effect with the small room into which she’s squashed (pictured above) doesn’t look like she’s on stage at all, that works extremely well – it looks like pure film.

Actually that scene works very well on film because you can just close in and lose everything around her. On stage you’ve got a mass of black, giant legs either side of her, and even though you got the idea she was quite dwarfed, whereas on film you can really get in and see her, I think it’s terrific.

Did you actually direct any of the camera angles to pick out what you wanted?

No, but we had a lot of meetings with Jonathan, he came and was wonderful in the creative process, he was there as it was being put together. So he knew the ballet very well by the time he got into it with the cameras. And we talked about placement of a few cameras, but it was nice – he included me in the editing process so I was able to do a bit of that too.

When did Simon Russell Beale (pictured below as the Duchess) come into it? I remember him having an inkling of doing more dance when he executed those entrechats in the National Theatre production of London Assurance.

Yes, I saw him in London Assurance and that was what gave me the idea to ask him to play the Duchess in Alice. Because that scene is kind of a tricky one, it’s not really a storytelling scene; Alice walks into this mad domestic mayhem, and it bothered me how we were going to convey the Duchess, whether she was going to be one of the dancers in the company, a dancing or a drag role, and she was based as a character on one of the ugliest members of royalty in Europe – an Italian duchess. Anyway, it seemed like a lot of fun, Simon moved really well in London Assurance. I knew he would act it so brilliantly and also bringing him in as an influence on the dancers - having a really great actor in the room gave them the opportunity to see how he created this role without words. How he pushed his body and character to the limit was a really great lesson for all of us.

Yes, I saw him in London Assurance and that was what gave me the idea to ask him to play the Duchess in Alice. Because that scene is kind of a tricky one, it’s not really a storytelling scene; Alice walks into this mad domestic mayhem, and it bothered me how we were going to convey the Duchess, whether she was going to be one of the dancers in the company, a dancing or a drag role, and she was based as a character on one of the ugliest members of royalty in Europe – an Italian duchess. Anyway, it seemed like a lot of fun, Simon moved really well in London Assurance. I knew he would act it so brilliantly and also bringing him in as an influence on the dancers - having a really great actor in the room gave them the opportunity to see how he created this role without words. How he pushed his body and character to the limit was a really great lesson for all of us.

Because it does seem that the Royal Ballet is getting better at having dancers expressing themselves facially, not just with the rest of the body.

And of course you do get the opportunity to get in there and see it closer in the camera, things do get lost when you’re in the audience. That’s what I’ve enjoyed most about what I’ve seen of the film: it really is a whole different medium.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

A really interesting