Sci-Fi Week: 2001: A Space Odyssey | reviews, news & interviews

Sci-Fi Week: 2001: A Space Odyssey

Sci-Fi Week: 2001: A Space Odyssey

The unassailable mother ship of science fiction movies is a sacred cow

No Gravity or Interstellar has challenged the might and influence of 2001: A Space Odyssey: its re-release this week is one of the movie events of the year.

Culturally as well as cinematically, of course, it remains the dominant icon of Final Frontiersmanship. Its opening in May 1968 (April in the US) pre-empted Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin’s moonwalks by nearly 16 months – an unparalleled act of scene-stealing. Kubrick’s use of the thunderous fanfare in Richard Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra - which suggested that extending Manifest Destiny to space recast the American “rugged individualist” as a Nietzschean Übermensch - was triumphalist. Yet the malfunctioning of the talking computer HAL carried a warning against Promethean overreaching similar to that in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

Culturally as well as cinematically, of course, it remains the dominant icon of Final Frontiersmanship. Its opening in May 1968 (April in the US) pre-empted Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin’s moonwalks by nearly 16 months – an unparalleled act of scene-stealing. Kubrick’s use of the thunderous fanfare in Richard Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra - which suggested that extending Manifest Destiny to space recast the American “rugged individualist” as a Nietzschean Übermensch - was triumphalist. Yet the malfunctioning of the talking computer HAL carried a warning against Promethean overreaching similar to that in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

Seeded by the 1948 Arthur C. Clarke story “The Sentinel”, 2001 was developed by Kubrick and Clarke into an enigmatic four-part “experience” short on exposition and dialogue. In “The Dawn of Man", a tribe of Pliocene-era ape-men is dislodged from a waterhole by a rival clan. When one of them (Daniel Richter, pictured above in costume) receives rudimentary imagination and the will to violence from the transmissions of a mysterious black monolith, he bludgeons an enemy to death and his tribe retakes the waterhole. Ergo, all humans have the capacity for inflicting injury.

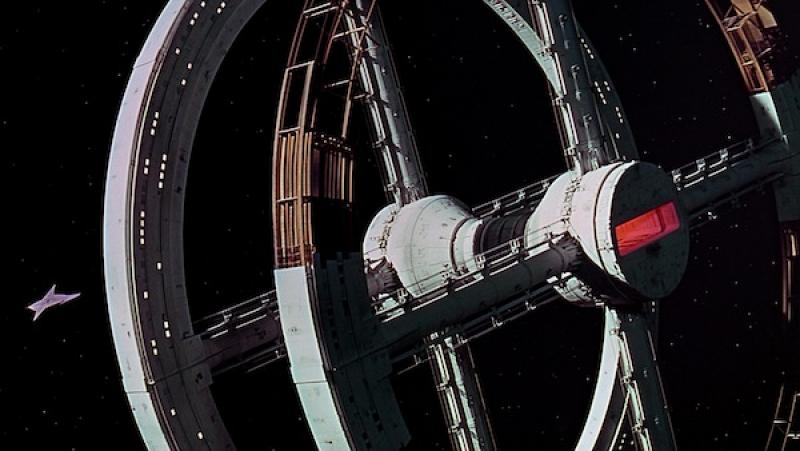

The untitled second chapter (or second part of the first) unfolds in space in 2001. During a stopover on a station orbiting Earth, the American scientist Dr Floyd (William Sylvester) conceals from Soviet scientists (Margaret Tyzack, Leonard Rossiter) why he’s flying to the moon base Clavius. On arrival, Floyd explains to its top brass that a monolith has been discovered there. It emits a piercing signal when his team approaches it at the dig where it was unearthed.

In “Jupiter Mission: Eighteen Months Later”, Discovery One astronauts David Bowman (Keir Dullea, pictured left) and Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood), who are travelling to that planet with three cryogenically frozen colleagues in hibernation, realise that HAL, which controls their ship’s systems, has become error-prone and paranoid. After it attacks the crew, Bowman – left alone to pilot the ship – learns they’d been tasked with investigating the meaning of the lunar monolith’s signal.

In “Jupiter Mission: Eighteen Months Later”, Discovery One astronauts David Bowman (Keir Dullea, pictured left) and Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood), who are travelling to that planet with three cryogenically frozen colleagues in hibernation, realise that HAL, which controls their ship’s systems, has become error-prone and paranoid. After it attacks the crew, Bowman – left alone to pilot the ship – learns they’d been tasked with investigating the meaning of the lunar monolith’s signal.

In “Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite”, his extra-vehicular pod is sucked into a coruscating psychedelic corridor – the “Star Gate” sequence – and plunges through space for what could be aeons. His destination is apparently a state of inner consciousness designed as a Louis XV hotel suite where he can observe his own ageing prior to a climactic encounter with another monolith.

All this amounts to a thin narrative and a movie as cryptic as Alain Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad (1961). Revelatory though Kubrick’s quasi-art-house sci-fi epic seemed, not all its elements were original. The celebrated match cut – a bone used as a tool and weapon by Richter’s hominid morphs into a 21st-century satellite when he jubilantly throws it in the air – was copied from Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s A Canterbury Tale (1944), in which a medieval falcon turns into a swooping Spitfire. Kubrick’s rotating space station and weightless space men were anticipated by those in Pavel Klushantsev’s Soviet documentary The Road to the Stars (1958).

Nonetheless, the synthesis and the glory were all Kubrick’s, and so 2001 single-handedly opened the door to the space operas made by George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, Ridley Scott, and more playfully by John Carpenter. Most of these filmmakers – as well as Martin Scorsese and Michael Mann – revere Kubrick, though he clearly influenced them more as a supreme technocrat than as a film poet.

It’s significant that, as an American based in Britain, Kubrick appealed more to Hollywood’s “movie brat” generation – Scott and Christopher Nolan aside – than to such English or Anglo-Celtic cine-alchemists as Powell, John Boorman, Ken Russell, Nicolas Roeg, and Derek Jarman. Kubrick did strive for alchemy in Star Gate’s trippy abstraction (pictured above) – astral traveller Bowman (his name suggesting the 2001 fan behind “Space Oddity” and “Starman”) being posthumously reincarnated as a presumably immortal cosmic foetus (pictured below), an embryonic E.T. no less. The wide-angle bedroom scenes were a misstep, however, as was the use of Johan Strauss II’s The Blue Danube – Kubrick indulging his taste for the baroque while eschewing narrative coherence.

It’s significant that, as an American based in Britain, Kubrick appealed more to Hollywood’s “movie brat” generation – Scott and Christopher Nolan aside – than to such English or Anglo-Celtic cine-alchemists as Powell, John Boorman, Ken Russell, Nicolas Roeg, and Derek Jarman. Kubrick did strive for alchemy in Star Gate’s trippy abstraction (pictured above) – astral traveller Bowman (his name suggesting the 2001 fan behind “Space Oddity” and “Starman”) being posthumously reincarnated as a presumably immortal cosmic foetus (pictured below), an embryonic E.T. no less. The wide-angle bedroom scenes were a misstep, however, as was the use of Johan Strauss II’s The Blue Danube – Kubrick indulging his taste for the baroque while eschewing narrative coherence.

Like all of Kubrick’s films from Dr. Strangelove (1963) onwards, The Shining excepted (1980), the unassailable mothership of science fiction movies is something of a sacred cow. It is often described as transcendent, but what does it transcend? Are the alien-planted monoliths supposed to represent science’s obviation of God, or a secular reconsideration of God’s identity? What does Dr Floyd’s announcement about the discovery of the four-million-year-old monolith portend, apart from more portentousness? Movies that ask more questions than they answer can be exhilarating, but in blinding us with pseudo-science 2001 disdains meaningful debate. There is more Carl Sagan than sagacity in Kubrick and Clarke’s speculations.

If that is not enough, 2001 is humourless and so glacially paced as to be ponderous. It fetishises spacecraft but is uninterested in human behavior and feelings. The performances are stiff, the characters almost as inanimate as HAL. That was surely intentional – a gesture toward a future in which homo sapiens and machine life will fulfil their cyborg destiny (as more radically visualised, for example, in 1989’s Tetsuo: The Iron Man). The problem is it looks like bad acting.

If that is not enough, 2001 is humourless and so glacially paced as to be ponderous. It fetishises spacecraft but is uninterested in human behavior and feelings. The performances are stiff, the characters almost as inanimate as HAL. That was surely intentional – a gesture toward a future in which homo sapiens and machine life will fulfil their cyborg destiny (as more radically visualised, for example, in 1989’s Tetsuo: The Iron Man). The problem is it looks like bad acting.

The spectacle of pristine spacecraft gliding through or spinning in the galaxy is impressive and 2001 does improve on repeated viewings. But it has a grubbier analogue that makes an infinitely deeper metaphysical probe into the moral and psychological consequences of space exploration: Solaris (1972) was directed by the Soviet master Andrei Tarkovsky, whose comments on Kubrick’s artifice are worth reading.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Comments

Clearly, we see the movie

Yes, we do see it