Donghoon Shin has a taste for the esoteric – a love of labyrinths, literary puzzles, and contradictory aspects of the self. One of his favourite authors is the Argentinian essayist and short-story writer, Jorge Luis Borges, whose perspective flipping explorations often feel like the verbal equivalent of art by Escher.

“I loved his games of intertextuality when I was young,” he tells me on a Zoom call. “I was already fascinated by labyrinths, partly because of the video games I’d played. So it was really exciting to experience the way he used the concept and perception of the labyrinth. That was why his work touched me so strongly.”

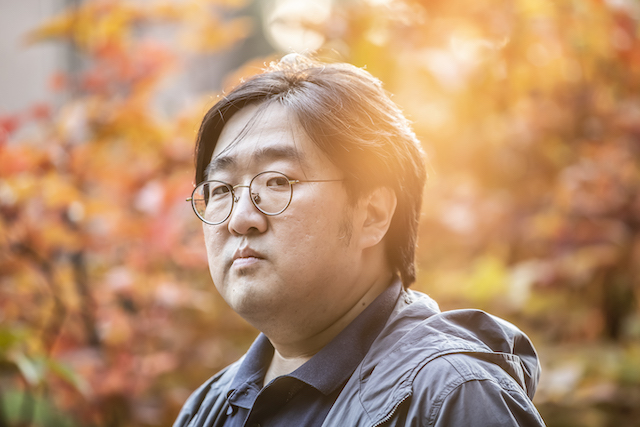

Shin’s first piano concerto will be performed by Seong-Jin Cho (pictured below) at the Barbican this November, marking the first time that classical music has been included as part of London’s annual K-Music Festival. His awards include the 2022 Claudio Abbado Composition Prize (a huge turning point for him) and a 2019 UK Critics’ Circle Award for Young Talent, while the orchestras that have commissioned him include the Berlin Philharmonic and the London Symphony Orchestra. Yet it’s clear that words are the great love of his life – it’s no surprise that he initially wanted to be a novelist. Certainly he has a breadth of reference that implies that he could still be one if he chose to turn his hand to it.

“When I was growing up I also loved writers like Kafka and Tolstoy,” he says. “In South Korea both German and Latin American literature were huge, and there were many translations to choose from. However, Victorian literature from the UK was not so popular so it was only last year that I read George Eliot’s Middlemarch. I felt it was my greatest achievement of the year. Every single aspect was like a piece from a jigsaw puzzle, it’s so well-crafted and the last page is so touching and so beautifully written.”

“When I was growing up I also loved writers like Kafka and Tolstoy,” he says. “In South Korea both German and Latin American literature were huge, and there were many translations to choose from. However, Victorian literature from the UK was not so popular so it was only last year that I read George Eliot’s Middlemarch. I felt it was my greatest achievement of the year. Every single aspect was like a piece from a jigsaw puzzle, it’s so well-crafted and the last page is so touching and so beautifully written.”

Even though Shin (main picture, and below) ended up writing music instead of books, many of his compositions are directly related to specific pieces of writing – so, for instance, Threadsuns for viola and orchestra was inspired by an enigmatic, wistful short poem by the Romanian Paul Celan. His chamber orchestra piece, Of Rats and Men, tips its hat – not to John Steinbeck, as the title jokingly suggests – but to Kafka’s short story Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse Folk and Robert Bolaño’s Police Rat. The relationship is complex: beyond the obvious point that music is “more abstract” than literature, Shin feels strongly that “the system and the grammar for both are very different, so you can’t really talk about translating words into music. What I try to do is get inspiration from the atmosphere in a piece of written work.”

So what piece of writing has inspired his piano concerto? He smiles. “Actually this piano concerto is inspired by one of my favourite composers, Robert Schumann.” Yet the literary connection is still there. “Schumann was very inspired by literature – his father was a really big bookseller.” One of Schumann’s favourite authors was the German Romantic author Jean Paul, a writer who was intrigued by dual characters representing different aspects of the same person. “Schumann talked about his own alter egos,” Shin explains. “He even gave them names: Florestan [for the wild, passionate one] and Eusebius [for the more tranquil, thoughtful one].”

He feels this duality is particularly appropriate for a concerto written for Seong-Jin Cho, one of the new generation of superstar pianists who has recently dazzled critics with his recordings of the entirety of Ravel’s piano music for the 150th anniversary of the composer’s birth. “I've known Seong-Jin Cho for three years,’ he says. “Kathryn McDowell, the [outgoing] managing director of the London Symphony Orchestra introduced us to each other. When I write a concerto, or chamber music, it’s a collaboration with the person or people I’m writing for – they, in a way, are my greatest inspiration. Seong-Jin Cho has a very interesting character; he can be very introverted and shy. But when he plays on stage, you can see the fire.”

“I’m the same as a composer,” he continues. “I’m also quite an introverted person, and I like to isolate myself rather than socialising with people. All of us as human beings have this double sidedness. After all, the entire world is made up of contradictions – life and death, joy and sadness.”

Shin has lived in London for the last decade, but he spent his formative years in South Korea. How does he feel his Korean identity impacts on his music? “The truth is that South Korea was already very westernised when I was born there,” he replies. “After the Korean War [which ran from 1950 to 1953] almost everything was destroyed, so we had to rebuild the country from scratch. The US and the UK and several European countries helped. So I was exposed to all sorts of influences – the first composers I really loved were Mahler and Alban Berg. My father – who was a scientist – listened to everything from Led Zeppelin to classical, and my mother encouraged me to read literature.” Culturally voracious (Shin also adores jazz musicians including Pat Metheny and Keith Jarrett), it’s perhaps unsurprising that it wasn’t till he was in his early thirties and studying with the composer George Benjamin that Shin found his true voice. “I cannot really forget the first lesson that I had with George,” he says. “He read through the score in silence for almost half an hour. Then he closed it and said, ‘I think you are born to be romantic composer. I don't understand why you are trying so hard to restrict your emotions.’ That for me was a real turning point.”

Culturally voracious (Shin also adores jazz musicians including Pat Metheny and Keith Jarrett), it’s perhaps unsurprising that it wasn’t till he was in his early thirties and studying with the composer George Benjamin that Shin found his true voice. “I cannot really forget the first lesson that I had with George,” he says. “He read through the score in silence for almost half an hour. Then he closed it and said, ‘I think you are born to be romantic composer. I don't understand why you are trying so hard to restrict your emotions.’ That for me was a real turning point.”

Classical music is currently proving extremely popular among young South Koreans – pianists like Cho and Yunchan Lim have huge online followings which are translating into sold-out concert halls wherever they play. Why does Shin think this is happening right now? “This is just speculation,” he replies, “but I think part of it is the fact that in East Asia classical music isn’t part of our tradition. So the younger generation doesn’t feel that it belongs to older people. The fact that it’s so easy to track down on the internet too – in a way that it wasn’t for me even when I was at university – also helps. A strong part of the appeal is that they’re just discovering it for themselves.”

Add comment