Have you ever wondered why the Steinway grand piano is invariably the instrument of choice in every hall you visit, great or small? Why do the halls in question not offer a choice between two or three pianos of different manufacture, as so many did before the Second World War? How is it that the hand-crafted pianos pioneered by Julius Blüthner in Leipzig from 1853 onwards, and still being made to the highest specifications on a different site just outside the city, don't usually get a look-in?

Famous for their layered, mellow richness, cited by more than one great pianist as enablers for inspiration, preferred in the Moscow and St Petersburg Conservatoires - Prokofiev and Shostakovich played them, and their personal properties still survive in Russia - and favoured from Brahms and Liszt through to Arrau, Leonskaja and Pletnev, these great instruments are little seen and heard on the concert scene. Visiting the miracle that is the Blüthner factory today, I got a good idea why, and how keeping it in the family has been proof against the vicissitudes of hostile fortune.

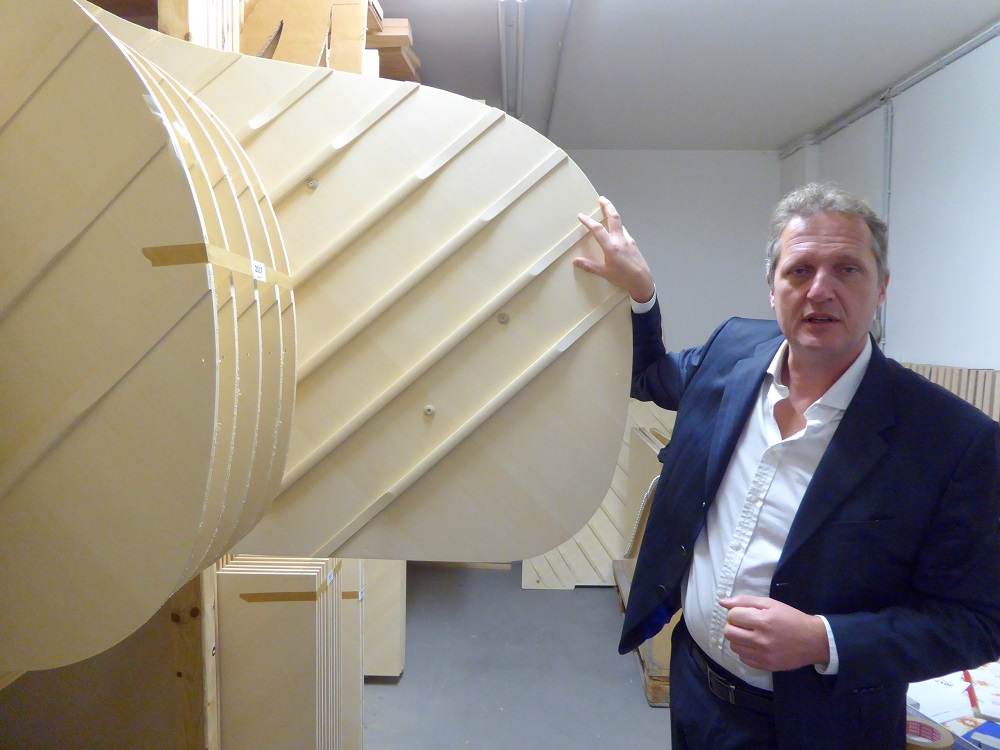

The miracle could have disappeared from sight: the total destruction of the Blüthner factory in the bombing of the Second World War, along with the bases of other great European piano manufacturers, could have simply seen the name go under when the centre of gravity moved to Steinway in the New World. As I was told by Christian Blüthner-Haessler, the great-great-grandson of mighty Julius, now on charge of the company's sales and financing while his brother Knut works as master piano-maker, "after the war, other manufacturers were a bit frustrated that their position in the market was challenged by an American company, and asked why. They started doubting their own heritage because the ownership had changed and so then they thought, OK, let’s adopt that design principle and we’ll see if we can be more successful. That's never the way to go and now 50 years later it’s a proven fact. Blüthner stuck to its authentic sound and design features - refined, of course, and developed further, because there should never be an end to small improvements." (Christian Blüthner-Haessler pictured below with soundboards in the factory)

I could at least grasp the various stages of piano-building as Blüthner-Haessler guided me round the factory, a kind of Tardis which looks small and intimate enough from the showroom end but unfolds into a seemingly endless series of rooms which allow you to follow the process from start to finish. Even the launch-pad is different from that of most piano factories, unique according to Blüthner: the wood arrives here for outdoor seasoning - spruce from the Black Forest, red beech from the Harz mountains and European maple. In looking at the components as they're made, you can clearly see how red beech is used for the inlay, spruce in the next layer and maple for the capping and bridge of the soundboard - a thing of great beauty in craftsmanship. The day of my visit few of the craftsman were on site, but all 4,500 components could be seen on close inspection.

For all the internationalism, the extension into the Far East market - where Blüthner has a hand in a huge Chinese festival of 40,000 participants, with a mere thousand in the final - and the indebtedness to the London base after the war, Blüthner remains a proud citizen of Leipzig. When Julius Blüthner allied his craftsmanship with business acumen to establish international connections in the mid 19th century, the city was a musical mecca. It had the first professional piano school, in the conservatory founded by Mendelssohn, the vital press of the Neuer Zeitung established by Schumann; it remained the city of Bach, with the Thomaskirche as the spiritual centre of the musical universe; it was brimming with trade and wealth, which, as Blüthner-Haessler pointed out, "doesn't hurt to establish a piano company".

For all the internationalism, the extension into the Far East market - where Blüthner has a hand in a huge Chinese festival of 40,000 participants, with a mere thousand in the final - and the indebtedness to the London base after the war, Blüthner remains a proud citizen of Leipzig. When Julius Blüthner allied his craftsmanship with business acumen to establish international connections in the mid 19th century, the city was a musical mecca. It had the first professional piano school, in the conservatory founded by Mendelssohn, the vital press of the Neuer Zeitung established by Schumann; it remained the city of Bach, with the Thomaskirche as the spiritual centre of the musical universe; it was brimming with trade and wealth, which, as Blüthner-Haessler pointed out, "doesn't hurt to establish a piano company".

In the sink-or-swim post-war era, when Blüthner-Haessler trained elsewhere as a medical doctor, his father took the decision to continue the company under nationalised ownership and his brother trained as piano technician, master and designer, the Soviet dominance at least kept culture going. Twenty years after reunification, Leipzig is buzzing again. That same Gewandhaus where the young Christian Blüthner-Haessler would go to see Brendel as a god, having sat on his knee as a six-year-old when the pianist came, as so many did, on a visit to the family, is at the heart of the city's identity; posters proclaiming Andris Nelsons as the new music director of the Gewandhaus Orchestra were everywhere, from the station through to the old-town streets bustling with the best Christmas market in Europe. "Here you realise it’s not just a product, it's part of the cultural environment," remarks Blüthner-Haessler, "and it comes with an obligation and a responsibility, which is why I’m here".

- Anne Queffélec gives the latest recital in the Blüthner Piano Series at St John's Smith Square on 20 June

- Read classical reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment