Edinburgh, October 2015. Robin Ticciati is still flying high from a remarkable performance of Brahms's First Symphony, the start of an intended cycle with his Scottish Chamber Orchestra in his seventh season as principal conductor. After a revelatory dissection of the thinking that shaped the interpretation, we both look forward to the end of the experience later in the season, with the Fourth. As he puts it: "That begins to transcend symphonic norms, for me it becomes quite esoteric, and for that characterisation and world, and distance from the rabid searching of No 1, I hope the year will allow me to grow faster than I can."

Sadly it didn't. A totally incapacitating back injury put Ticciati out of action not only for the Fourth – to coincide with the performance of which this interview was originally targeted – but also for the productions he should have conducted at Glyndebourne the following summer. He was finally back with the SCO and a stupendous evening of the last three Mozart symphonies in October 2016, though still in some pain, and it's only now that his long-term ambition, recording the Brahms big four, has seen the light of day (see Graham Rickson's Classical CDs roundup for the week). Better still, he will conduct his Scottish orchestra in all four symphonies over two concerts at the Edinburgh Festival. His official farewell to the SCO after nine transformative seasons came at the end of March, and he moves on to very different ventures, but our conversation should leave no-one in doubt that the ideal collaboration between conductor and players has been achieved, if not perfected – for Ticciati, there is always work to be done – over his time there. I began with the specific quality of the hybrid sound he achieved, bringing some of the ideas and instruments of the authentic movement to a modern chamber orchestra just as his one-time mentor Charles Mackerras had done with the SCO before him. The immediate comparison was an odious one.

I began with the specific quality of the hybrid sound he achieved, bringing some of the ideas and instruments of the authentic movement to a modern chamber orchestra just as his one-time mentor Charles Mackerras had done with the SCO before him. The immediate comparison was an odious one.

DAVID NICE: I've just heard a disastrous Prom of Brahms One with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, which you'd think would be interesting, but it was dead in the phrasing. Among other things they used completely natural horns, and that doesn't work, I don't think. This fascinating idea of combining valves with the natural horn sound in a hybrid instrument, was that your idea?

ROBIN TICCIATI: That was Alec [Frank-Gemmill, principal horn of the SCO] and me wondering what we were going to use, actually that was me going to him, and that's the relationship over seven years one can have – look, I want the closest to period instruments we can have, but knowing that we've got modern strings and just finding that exact blend of sound, that takes time. The first week I was here in 2009 I did Brahms Two, and I thought after that, I need to go away from this composer with this orchestra, to find out what I really want to say with this music, because I felt the travel from doing it with a symphony orchestra, where you can only inherit a lacquered tradition of Teutonic falsities – you know, what is tradition when you get there? And so going through our Berlioz and Schumann, the idea of chamber music in Haydn, everything, text, vocal, everything to do with recitative and gesture in music, and when you think of Brahms, you think of Schutz, you think of Bach, you think of text and singing.

And the songs of Brahms are equal to the symphonies and chamber music among his achievements.

Exactly. And then about two years ago I felt I'm ready to come back to it for this season, and I felt, you never go into something thinking you want to say something, but I think I have something to say now. It's been this combination of reading Steinbach, reading the letters, thinking about text, working with them, of course being influenced by their history with [Sir Charles] Mackerras, and the whole thing, and my own personal freedom of music making, this balance of head and heart I try to get, and absolute rigour to the text – leggiero, appassionato, dolce, pianissimo – what does it mean, how do we do it? And then at the end opening your arms and just letting people play. That's a big summary of how I feel I got to last night, and it's been a long time.

Most conductors seem to feel they have to do Brahms cycles, and there was a phase about 10 or 20 years ago when everybody did it, and I thought, I don't want to hear this. It was when Jurowski took them up again, and he had very fresh things to say.

Most conductors seem to feel they have to do Brahms cycles, and there was a phase about 10 or 20 years ago when everybody did it, and I thought, I don't want to hear this. It was when Jurowski took them up again, and he had very fresh things to say.

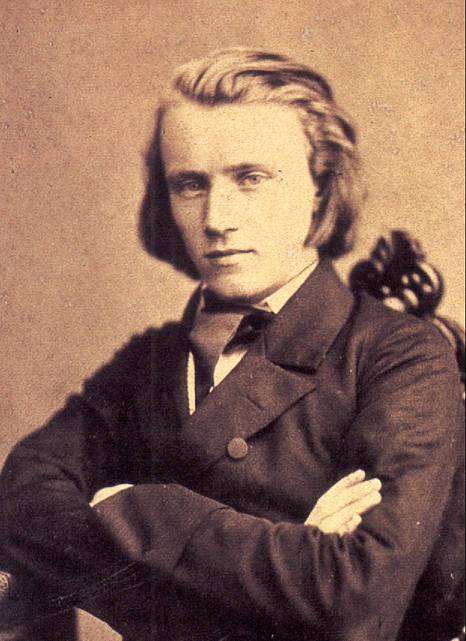

I had a wonderful talk with him about the opening of Brahms One (the composer pictured right in 1853, a year before the symphony), poco sostenuto, there's no tempo marking, he writes it after the main meat of the first movement, what does the 6/8 mean, how much of a compound dance form is it? Over the years we've got used to the thick sheepskin stick, beating, but what happens if there's an element of "in two", and so this first chromatic theme [sings] comes out as a syncopation. We had a lovely chat. He put me on to the Mengelberg markings, very interesting and close to the Meiningen tradition. I respect him so much when it comes to the idea of treating the score as a text, as something we have to look at – well, we don't have to, but I'm enjoying the rigour of looking at it with an intellect which then can free the emotional side.

And if you respond to the emotional side, that will be there anyway.

Exactly.

I remember the slow movement of his One, that was I think the most beautiful I'd heard, but then I was puzzled about the Third, I think that's the most difficult.

This is difficult. I see the third movement as an intermezzo, after the almost quasi-pathos of the second, we shouldn't touch the ground. I felt a little bit yesterday it was a tiny bit on the terra, the ground.

Not for me – that's the very phrase I thought of, that it didn't touch the ground.

Well I'm pleased if you thought that, but I hope we can go further.

The clarinets in the Berg [Violin Concerto, also on the programme], the last two minutes, the whole of the second movement and the third of the Brahms, had the quality of sound that was like on the other side, and that's probably what you want.

It means so much that you say that. There's this idea of Brahms and Berg as constructivists, and this thing of structure and numbers and hidden messages, and both of them obsessed by coding in music, I think that's fascinating, and in order to get to that poetic other side, to understand the hidden message, I'm pleased you got that. She [Isabelle Faust, pictured left by Detlev Schneider] is...

It means so much that you say that. There's this idea of Brahms and Berg as constructivists, and this thing of structure and numbers and hidden messages, and both of them obsessed by coding in music, I think that's fascinating, and in order to get to that poetic other side, to understand the hidden message, I'm pleased you got that. She [Isabelle Faust, pictured left by Detlev Schneider] is...

...the total musician.

That really moved us so much. And for us what's so exciting is that that isn't a repertoire piece. Hopefully nothing with this orchestra is a repertoire piece, but you know what I mean when I say that. We had a three hour rehearsal before she came, then she came and we worked.

And she listens to everything – the Abbado mentality, just listen.

Exactly, just listen. So I'm pleased also that that connection of other world you felt in the programme.

What I was going to say about Jurowski in that third movement was that it felt just a little too fast. You were never slow but it didn't feel fast. It's really difficult to gauge that.

Poco allegretto, and the fact that Brahms changed over 12 years the markings to each movement at least three times. So this idea of tempo and heartbeat is so complicated.

And the fluidity of that movement.

Exactly. And when you say fluidity, it makes me think of rubato, the thing that I try – try is the wrong word, the thing that I wanted to embrace and feel free with the orchestra, just the fact that we can just go. And we have stories of Brahms playing piano trios just moving forward and Clara turning the pages, what are you doing there? We know that he was so impulsive and that's the thing I feel I can achieve here with the orchestra, we can risk just going, and then really stopping, and this idea of pianistic rubato with an orchestra, to get to a place when you can trust your own interpretation and your own rubato, and the players will just come with you, this takes time, but yesterday it felt a bit like – well, not so much a watershed, but a next moment.

And rubato without the feeling that you're pulling it around. I don't want to diss yet another performance, but what I've just come from, we're doing a live CD Review [for BBC Radio Three] on Saturday, and the other reviewer has chosen the Barenboim/Dudamel recording of the Brahms concertos.

I haven't heard it yet.

I find it unbearable because it is so slow, and so without the inner pulse. There can be grandeur in Brahms without pomposity, surely?

I think it can be noble. There's nobility, there's Kraftigkeit, there's also a sense of Augenblick and theophany but even with Brahms – you think of the influence of Beethoven but also the influence of Bach, of baroque trope, it's dance form, it's counterpoint, and so I think rarely does the word "grand" come to my mind.

Ashkenazy did the Second almost like ballet music. That was a real revelation as well, the idea that Brahms was this big man who also has this dance lightness.  It's amazing to think Hans von Bülow [pictured above with the Meiningen Orchestra, Brahms's ideal, in 1883] describing the first as Beethoven's Tenth Symphony, what is that, how does he escape it? The thing that I find so wonderful about the First is the aborted version that turned into the Serenade, the aborted symphony that turned into the First Piano Concerto, you know, the most anticipated symphony, and I think what's wonderful, since you mention other interpretations, this is a piece that certainly I feel has so many questions, so many ponderables, I feel that it's a piece that even when I come back to it two years later will feel completely different. It has that inner flexibility and inner doubt that somehow you know this is so fluid as an interpretative mission.

It's amazing to think Hans von Bülow [pictured above with the Meiningen Orchestra, Brahms's ideal, in 1883] describing the first as Beethoven's Tenth Symphony, what is that, how does he escape it? The thing that I find so wonderful about the First is the aborted version that turned into the Serenade, the aborted symphony that turned into the First Piano Concerto, you know, the most anticipated symphony, and I think what's wonderful, since you mention other interpretations, this is a piece that certainly I feel has so many questions, so many ponderables, I feel that it's a piece that even when I come back to it two years later will feel completely different. It has that inner flexibility and inner doubt that somehow you know this is so fluid as an interpretative mission.

I suppose that's the thing about Bruckner too, that it should be about doubt. I don't want the interpretation to be assured. Coming from Haydn must also have given a different perspective.

Definitely. Probably for me more, musicologically I'm not so sure, but in terms of orchestral playing, of course they're a chamber orchestra so they play chamber music, but the thing about Haydn with us is that it must take us by surprise not for the sake of it but it must feel so on the moment, and that level of connection that we have helps in making Brahms One not feel like a relic.

You have developed this relationship with the players, and I've enjoyed seeing them work elsewhere – getting to know [double bass player] Nikita Naumov and Alec Frank-Gemmill when they were playing in the Estonian Festival Orchestra.

This is the thing, that it's the quality of these players that's so wonderful, and for me it's not just their playing quality, it's their approach to what it is to be musicians, and I think I've said this to you before, but you feel they wake up every day and they decide again to be musicians. There is this feeling that it isn't just something that you fall into. And I think that to have that as an orchestral player is what's invaluable.

And that they'll want to carry on playing chamber music, for instance, in the summer break. Did you have to work with Alec (Frank-Gemmill, pictured right by Jen Owens) on the special quality of the horn calls in the finale?

And that they'll want to carry on playing chamber music, for instance, in the summer break. Did you have to work with Alec (Frank-Gemmill, pictured right by Jen Owens) on the special quality of the horn calls in the finale?

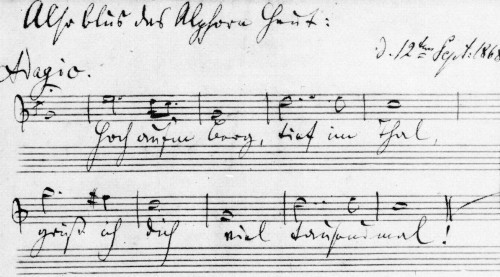

I was so thrilled with this. When we first played it through, as one always does, even with musicians whom I know so well, we play the piece through, I try and show everything without using my voice, it's just me listening to them, them watching me. Just to feel – of course there is sometimes a moment in bar three in the first run-through where you might stop and say, this for the whole piece, please, just to cement one idea in their minds. But we came back and we started the last movement again and we got to the horn call and at about the third bar I said to lovely Alec, I said, do you know the text? Really either thinking he would say well, of course or no, not at all, and he said, not at all. So this idea of explaining to him that Brahms wrote a postcard to Clara when they were walking up that mountain they were obsessed by, the Rigi [near Lucerne in Switzerland] – "hoch auf'm Berg, tief in Tal, grüss ich dich viel tausendmal" – "high up on the mountain, deep down in the valley, I greet you a thousand times" (pictured below). The melody has text. And he wrote that horn theme with that text in mind. I told Alec that and then I said, so let's remember the Andante and remember the fact that this is about sentence structure as well as absolute melody. And I didn't say anything else – and it changed 100 per cent. And I suppose that's a beautiful part of the process, that it's not about piano, forte, crescendo, diminuendo – it's about an idea and I find the more one immerses oneself in the psyche of the composer, not necessarily that you will share that with the players, it can permeate one's interpretation somehow. I'm talking now and I hope it will be for years that it grows. But that was a lovely moment.

That you know what he intended, but you can represent it as you please. I've never read that in any programme note. I knew it was supposed to be an Alphorn.

That you know what he intended, but you can represent it as you please. I've never read that in any programme note. I knew it was supposed to be an Alphorn.

On that question of hybrid horns, I didn't know about the development of the flute that it had got keyed somewhere in his compositional life, and he preferred to keep with the wooden flute, so there could be flutes doing portamenti. Of course it's probably not news to other people, but it was news to me. We haven't done that this week. Alison [Mitchell, SCO principal flautist] is beginning to go onto the wooden flute for certain things, and we need to find a second who does it, and that takes time, but I loved reading that. He didn't want the advancement.

And when you hear period trumpets, that's a completely different sound. When you hear Bach like that, how could you settle for anything else?

I know, with the D major Suite.

And the timps established the character of the opening of the Brahms symphony immediately.

That's calfskin. Matt is new and came in during my time here, and I'm very obsessed by timp sound in this repertoire and with a chamber orchestra. I think it influences phrase, it influences the sound of the bass, and it's an active musical element. Very much in the Schumann I wanted something flecked, febrile, really dry and wooden. With the Brahms we had a long conversation about what instruments Tim was going to use. He just thought that we could go one step further with a bit more amplitude, a little softer felt sticks, and I said, brilliant , let me hear it at the first rehearsal and have some other sets around, and we stuck with these. It's calf-head, old copper bottoms. And the feeling of that opening the sound, we worked on it a lot. I wanted to feel that we had sostenuto and tension, but I also wanted to feel that we had travel, and I somehow also wanted to escape, that we start the symphony in the middle of the narrative. It's not in a sense a grandiose beginning, but it is this aspera, this suffering immediately.

It's parallel with the First Piano Concerto.

Exactly. That D. It also has to travel.

And we had Leonskaja with Okko Kamu conducting the SCO in both piano concertos in one concert. Last night, the diaphonous quality – you were always aware of the horns but they didn't dominate. I got that sense in the Academic Festival Overture too – I was hearing phrases which were developments of ideas under themes which I always thought were the main themes. Everything comes through.

It's bad if that comes out academically, that overture. But the idea of the lines is really essential. I love that piece, for me it was the first time yesterday, and a lot of people have either played it a million times or studied it so much at some point in their lives that it's become a piece that doesn't hold so much mystery any more. But (sings lyrical theme), that's a Lied, there's a text somewhere there. And just his use of the triangle, to wait for that final G pedal and it comes in on the dominant pedal, not a tonic resolution, it gives something of expectation, I said, now look, you've got to play it in a way that all your Christmases have come at once. There has to be rusty jangle. It's lovely talking to the percussionists – they're not members of the orchestra but I always have the same team with me here, and it's lovely that they know when it's to do with cymbal sound or the type of bass drum, the skin, they'll always bring three or four options so we can find the right type of rust.

But this is exactly carrying on the kind of Mackerras tradition, I remember his recording of Mozart's The Magic Flute with the SCO in 1991, his demand for the right sort of glockenspiel and timps, and the orchestra are used to that.

Exactly, it's in the DNA.  Do you think the other three symphonies will require different approaches, that there will be fresh questions?

Do you think the other three symphonies will require different approaches, that there will be fresh questions?

Yes, I definitely think so. I think in terms of approaching Brahms the composer and his relationship with symphonic form, I think Four will be amazing – how does one put it into words, maybe this really is absolute music in the way that Three is so much about his relationship with Clara and having that final statement. There is something very huge about that symphony, and then Two and Three are how you get there, as well. Of course they're not just transition pieces, but that gives you an idea of what I think about the shape. Two, the hovering black wings at the beginning of the introduction when the trombones come in, to the blazing D major light of the last movement. You've also got that 19th century telos, journey, which is clear in One but perhaps less fulfilled. You get to the chorale at the end of one – how golden, how triumphant, yet how pressed should it be? You don't want it to sit and be comfortable, and yet you don't just want to run through it, there has to be space, so the idea of the apotheosis at the end of each symphony is a big thing. Look at Three, then Four comes along. So I'm thinking about the rest of the journey – well, it's trying to understand Brahms the man, isn't it, through his music, and trying to deliver that in a way.

You did a wonderful thing with the coda, which was very fast, and then the last couple of bars were slightly slower.

Just this idea that the (sings rhythm) is suddenly, OK, a race to the finish, C pedal, instability, but in no way kind of comfortable. When you reach the final subdominant (sings again)... I said, look, we must get this balance of big vision and hot-blooded impulse, and I just felt these last chords, bam, bam, bam, let's really then go through, so it was a mixture of stretto and time, and I thought a lot about the way that he would feel reaching the end of a symphony, the way that in Beethoven Five you've got dominant, tonic, dominant, tonic, OK, we're home, we believe you. With Brahms it's a bit shorter, of course, but I wanted this idea of what do the final chords signify, and want to make us feel about ending a symphony. Those are just the first thoughts about that. But I'm glad you heard that even there there was tempo variation.

I heard Barenboim and the Berlin Phil play it in the Sheldonian, and I have to say that most of the performance was pretty middle-of-the-road for me, but then in the coda it just knocked us for six, and everybody came out saying, my legs aren't with me. Suddenly something happened, what you expect from a Mahler symphony when you can't speak and walk. Thinking of the end of Three and this lovely diaphanous sound last night, I was wondering if the Elgar symphonies would be a step too far.

Gosh, wow.

Because I could hear that translucency would help.

Yes, of course, what a wonderful... but look, I think what I hear in your question is the fact that what does the psyche and what does the atmosphere of this orchestra bring to music making. And of course, what does Elgar need and so on.

And what you with your sense of rubato bring – that's what Elgar needs.

Interesting. So rather than just counting, you're thinking fluidity and escaping, well I hadn't thought about it but it's interesting the pieces that have a kind of childhood resonance, my relationship with Colin Davis, I would have been 13 or 14 when I got to know him, that was his second time of his doing the Elgar symphonies with the LSO, what am I trying to say? They need to tell me when it's time to do them. Put it this way, I absolutely love them, but they have to become more part of me, me, me. God, that sounds horrific, but you know what I mean.

I was thinking because of the exquisite division of strings you would hear all the inner parts.

Exactly. But I also have to be careful, this, obsession's not the right word, but discovering and doing music with SCO on such an intense level and being so forensic with the score, I've got to also know when – and this is what I'm also working on – when the sound world can also be thick and sometimes muddied if it needs to be and impressionistic, by which I don't mean wishy-washy because so often the technique was unbelievably scientific, but to know also when just to let the music have a fog as well.

Chiaroscuro and all that.

I think it would work very well, I'd also have to make sure that body, and our production of sound and tone, was ample enough, let's use that word, that could be to do with the number of strings. I've been inspired being here and being hugely influenced and inspired by John Eliot [Gardiner] and the [Orchestra Revolutionnaire et] Romantique and the kind of pieces that he does with that orchestra. It's not about chamber in size, it's chamber in concept.

That's an Abbado thing too. When the OAE did No 1 they had seven double basses. And I found out that most of the players had never played with the OAE before anyway, so it stopped really being an OAE performance. It was just too big and didn't work, but it was a big symphony. What size did Brahms want? Meiningen was small, wasn't it?

Meiningen was small, well, 30 strings and we had 33 yesterday. I saw how the conductor of the newly formed Boston [Symphony] Orchestra sent Brahms some seating plans about what would be his preferred choice. We have a picture, first and second violins are opposite each other, and then two groups of cellos fan out, violas in the middle and double basses behind the wind. So there's a whole thing about seating. I thought long and hard, what really do you gain if you split the cellos up, and our basses, there are four, so maybe not enough if it's behind the wind it has to really penetrate. But it's also interesting to think about set-up of musicians.

I've seen a lot of performances by British orchestras recently where the basses are to the left.

That goes to the idea of counterpoint in Bach, treble, bass, to have those together really as duet form and then inner counterpoint on your right, for most of my programmes here I do first, second, violas, cellos, basses on the right, but more and more this half-Germanic seating of having the firsts and basses together is really, really valuable. I don't think it comes with any sort of dogma but I really enjoy the concept.

That goes to the idea of counterpoint in Bach, treble, bass, to have those together really as duet form and then inner counterpoint on your right, for most of my programmes here I do first, second, violas, cellos, basses on the right, but more and more this half-Germanic seating of having the firsts and basses together is really, really valuable. I don't think it comes with any sort of dogma but I really enjoy the concept.

I was saying last night that Nikita [Naumov, pictured left by Marco Borggreve] does draw one's eye to him by the way he plays, and someone said in response, well, he is the leader from the bass, which is an interesting idea that you've got the leader in the violins absolutely central, but the leader of the basses makes it strong from that side of things.

Exactly. He asked some questions this week which I was so happy about because it was – not simple, but very basic questions which have complex answers about the polarity between tonic and dominant, and do we release onto the downbeat, or do you want us to go into that, or what type of resolution is that. In this repertoire the basses have their own separate lines frpm the cellos in Brahms, so already they're released, but to have players that think of the bass line as a sport and also as an extreme sport is brilliant, and that's what I love, when bass or cello players aren't obsessed by melody but are obsessed by function of a bass line which then in turn absolutely can affect the melody on top of them. And that goes with this orchestra back to all the work with Egarr and Herreweghe and Bill Christie in all the earlier repertoire that they do. So they take that in the later repertoire. He's a wonder.

Congratulations on the Berlin appointment [news had just broken of Ticciati's appointment as principal conductor of the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester, beginning in the 2017-2018 season]. You'd only worked with them once?

Well, it was difficult and not difficult at all. Like it actually happened here after one concert, the orchestra is very emotional in Berlin and has this beautiful mix of that Deutsche Kunst, deep culture and a hugely contemporary international flexibility. Those two worlds when we were doing Bruckner and Britten together – Cello Symphony with Isserlis, this is an extraordinary piece, the apotheosis of the final chorale.

Like the sail Captain Vere sings about at the end of Billy Budd. The sense of glimpsing something.

Exactly. And to think that it's just a seventh at the end, Steven would completely disagree with me, but I said I think it sounds so new and visionary, and yet it's just a dominant seventh. That was special and then Bruckner Four in the second half. Look, it just felt so right, so right, and when they approached me and asked, I didn't doubt it for one second.

Who is there now?

Tughan Sokhiev. And their history – Fricsay, Chailly, Maazel, Ashkenazy, it's got a wonderful history, a fighting history as well, its position in the radio, its position in Berlin, everything – it has an idea of what is music making behind it, that's also the thing for any artist, to see Berlin and the way that culture is so intrinsic to the way people breathe and walk. It's been really moving, even the odd person that's been in touch, Barrie Kosky from the Komische Oper, the community of Berlin says welcome. It's an extraordinary place, and I want to go and give myself to it.

Add comment