Q&A Special: Conductor Wolfgang Sawallisch on Strauss and Wagner | reviews, news & interviews

Q&A Special: Conductor Wolfgang Sawallisch on Strauss and Wagner

Q&A Special: Conductor Wolfgang Sawallisch on Strauss and Wagner

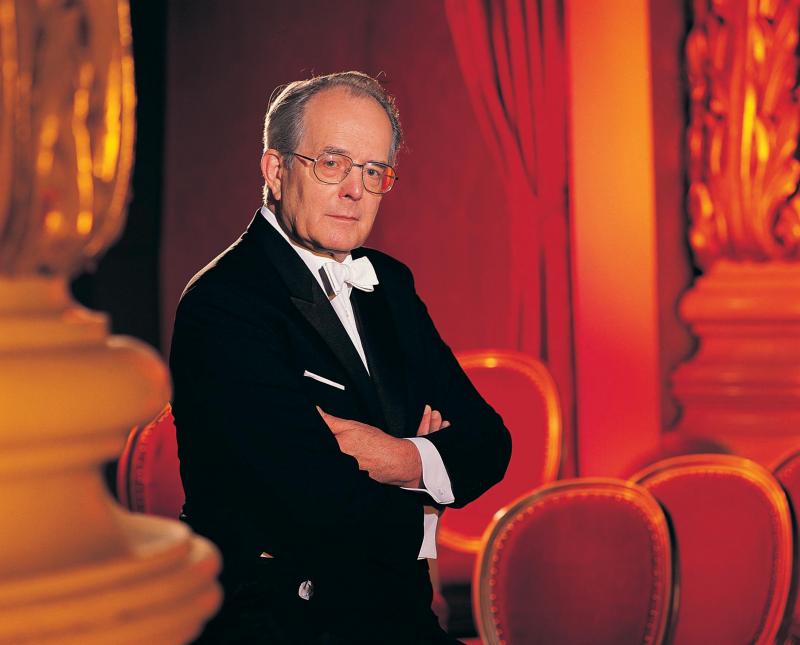

The great Bavarian conductor, who died on 22 February, talking in 1992 about his biggest musical loves

In many ways the most well-tempered of conductors, Wolfgang Sawallisch (1923-2013) brought a peerless orchestral transparency and beauty of line to the great German classics. Even the most overloaded Richard Strauss scores under his watchful eye and ear could sound, as the composer once said his opera Elektra should, “like fairy music by Mendelssohn”.

Courtesy of Gramophone magazine I met Sawallisch in Munich, his home town, at a time when he was about to leave behind political infighting and the temporary closure of the house (pictured below) for a new era in Philadelphia. During his American Indian summer, he worked wonders there over a decade, following a tetchy relationship between the players and Riccardo Muti. Sawallisch also achieved what his predecessors had not, seeing through a new concert hall for the players. And they needed it: the concert I heard in a converted theatre was acoustically dry and boomy, which made you wonder whether the famous Philadelphia string sound was partly a result of fighting so hard for a glow.

So many composers change at the end of their life to follow the line of contemporary thinking. But Strauss is so true to himself

Despite what he says in the interview about intending to focus on the core romantic repertoire in Philadelphia, Sawallisch surprised everyone there by taking on some thorny American compositions. His openness to innovation – exemplified in the interview by what he says with regard to Nikolaus Lehnhoff’s production of Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen in Munich – was revealed when he turned out to be among the first conductors to champion the streaming of concerts online.

Having been shattered by the death of his wife Mechthild, a former singer, in 1998 – they had been married for 46 years – he stayed on in Philadelphia, finally retiring to his estate in the Bavarian Alps from 2003 until his death. As the Philadelphia’s Conductor Laureate, he still made the occasional hero’s return, and played the piano to friends and visitors. It was a skill which had not only allowed a Philadelphia concert performance of Wagner’s Die Walküre to go ahead, when he substituted at the keyboard for a snowbound orchestra, but had also created many distinguished partnerships. His recordings of Strauss Lieder with Margaret Price and Brahms with Fischer-Dieskau are among the greatest.

We began with my effusions over the performance of Strauss’s second Viennese opera Arabella I’d heard him conduct in Milan – the only other opera house he would leave Munich for (he turned down engagements at the Royal Opera; and in his youth he had rejected major posts at New York’s Met and the Vienna State Opera on the grounds that he lacked experience).

We began with my effusions over the performance of Strauss’s second Viennese opera Arabella I’d heard him conduct in Milan – the only other opera house he would leave Munich for (he turned down engagements at the Royal Opera; and in his youth he had rejected major posts at New York’s Met and the Vienna State Opera on the grounds that he lacked experience).

DAVID NICE: That was such a clear and exhilarating performance. I didn’t believe an Italian string section could play so well [times have changed with Pappano’s leadership of Rome’s Accademia di Santa Cecilia]

WOLFGANG SAWALLISCH: I agree – I wanted it to be clean and classical. It is not an operetta, you understand. It’s really a great opera, ja, and one of Strauss’s most complicated, because all the themes are so fantastically involved in different orchestral colours, always small groups of notes, often the same notes, but very complex. Oh ja, it’s a very difficult but a good score.

You'd conducted it before in Milan.

Yes, you’re right, a Rudolf Hartmann production with two Italian designers [in 1970]. Then it was sung in Italian.

Your Strauss conducting generally is very natural, very detailed and always with short bursts of emotion, but never too much. Do you feel this much more an older tradition in opposition to the rather more sensational approach of a lot of Strauss conductors today?

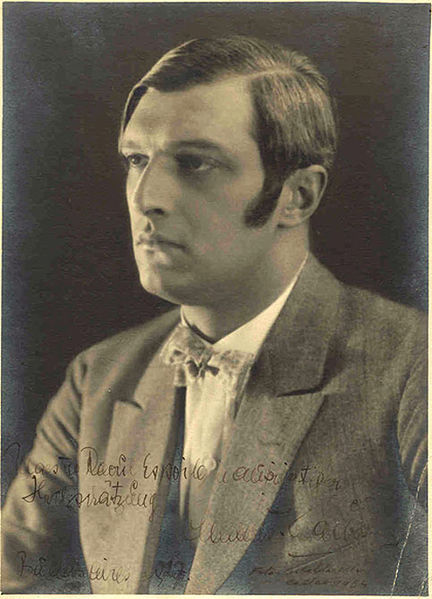

I can’t say. Personally my deepest impression came from the Strauss conducting of Clemens Krauss (pictured left in 1929), and certainly the complete recording of Rosenkavalier he did with this orchestra [of the Bavarian State Opera] immediately after the war is so clear, so easy, so simple. And I remember in the late 1930s I stayed here in Munich and I heard all the Strauss performances conducted by Clemens Krauss and without ever once thinking about the problems for the conductor. I was too young, you understand, but the impression I received of Krauss’s Strauss conducting was certainly a basis for my own later conducting, to try out the same elegance, light, not too loud, not too much German, you understand – I like a musically really international chamber music style with attention to details, so that’s true, but not too [imitates hard hitting with explosive ‘K’s] – like that.

I can’t say. Personally my deepest impression came from the Strauss conducting of Clemens Krauss (pictured left in 1929), and certainly the complete recording of Rosenkavalier he did with this orchestra [of the Bavarian State Opera] immediately after the war is so clear, so easy, so simple. And I remember in the late 1930s I stayed here in Munich and I heard all the Strauss performances conducted by Clemens Krauss and without ever once thinking about the problems for the conductor. I was too young, you understand, but the impression I received of Krauss’s Strauss conducting was certainly a basis for my own later conducting, to try out the same elegance, light, not too loud, not too much German, you understand – I like a musically really international chamber music style with attention to details, so that’s true, but not too [imitates hard hitting with explosive ‘K’s] – like that.

This presumably goes back to Strauss himself who was a very unsensational conductor –

Yes, even in the big scores of Salome and Elektra.

I believe you saw Strauss conduct.

I remember only one performance, it was in the early Thirties, I was perhaps 12, 13 or 14 maximum, he conducted [Mozart’s] Così fan tutte with himself on recitatives on the cembalo [harpsichord], he inserted always in the right places some themes of his own, of Till Eulenspiegel for example, and it was in the Cuvillies Theatre, the small house (Strauss conducting Cosi in Vienna in the 1930s below). I remember the cast, and it’s always very nice to meet some people who had seen the same production in 1932, 33 or 34, then we remember it together – but of course frankly I was much more impressed in my memory by his cembalo playing than by his conducting, I cannot say how fast or slow it was, but I remember the whole occasion was a special one.

Do you admire Rudolf Kempe as a Strauss conductor?

I liked him very much, we had a very nice friendship, and it was a great advantage for him that he started as an oboe player, so he was always very familiar with all the problems orchestral musicians have with Strauss scores, and I remember he very often conducted Salome in this house, and again it was absolutely clear, without too much force…he was a true musician.

I liked him very much, we had a very nice friendship, and it was a great advantage for him that he started as an oboe player, so he was always very familiar with all the problems orchestral musicians have with Strauss scores, and I remember he very often conducted Salome in this house, and again it was absolutely clear, without too much force…he was a true musician.

Do you think you share Strauss’s Bavarian characteristics?

No, I don’t think so.

You don’t feel that in yourself?

Of course, perhaps without knowing it, and I was Munich born like he was. Perhaps there is something in the air, of a Bavarian Baroque music, he felt like a Baroque man and that’s the same for me too. I like these Strauss pieces – Lieder, orchestral works, opera, everything, I like very much this sort of composition. And I like very much the fact that until his last minutes of his life he was always very clear and without changing his mind as a musician. So many composers change at the end of their life to follow the line of contemporary thinking, like Stravinsky. But Strauss is so true to himself.

What about this late opera, Die Liebe der Danae [there was a possibility at the time that EMI was going to record Strauss’s penultimate work for the stage, his "little mythology" about the affair between Danae and the ageing Jupiter]?

I LIKE it! And especially the last act. The first is sometimes a little artificial and constructed with the 54 bars and all the entrance of Jupiter. Ja, perhaps. But the last act, the farewell…

And the interlude…

It’s great. And this kind of horizontal music, like the Vier Letzte Lieder [Four Last Songs], not composed as it were, but like some kind of higher power about the composer, over the composer, and when Jupiter sings about his relationship with Maia – this is really very, very great music.

You’ve done it in stage performances alongside Salome and Elektra. Those are big pieces, sometimes very loud. That’s also true of Ein Heldenleben [which is what I heard him conduct in America]: did you feel the need to scale down or did it come very naturally, with the Philadelphia Orchestra?

Yes. I always had the experience that it is much easier for an orchestra to play like this than to play all kind of unnatural pffff overdriven sound, you understand? It’s much easier to play what’s written in the score, and for the strings to find the right feeling for the fast passages, to play the first and the last note, and in between to give only the impression of some sound. And I hope that during the next years I have the opportunity to study with the Philadelphia Orchestra – and it’s really a great orchestra – and to come closer to the orchestra, to my personal feeling about intelligent, convincing and interest sound. Not with big fortissimos, that’s too easy. But in the middle waves. This I would like to try out with the Philadelphia Orchestra because they have marvellous musicians, I’m sure they can do it.

Yes. I always had the experience that it is much easier for an orchestra to play like this than to play all kind of unnatural pffff overdriven sound, you understand? It’s much easier to play what’s written in the score, and for the strings to find the right feeling for the fast passages, to play the first and the last note, and in between to give only the impression of some sound. And I hope that during the next years I have the opportunity to study with the Philadelphia Orchestra – and it’s really a great orchestra – and to come closer to the orchestra, to my personal feeling about intelligent, convincing and interest sound. Not with big fortissimos, that’s too easy. But in the middle waves. This I would like to try out with the Philadelphia Orchestra because they have marvellous musicians, I’m sure they can do it.

Is there a lot of work to be done?

Perhaps, I will see. I did [Strauss's] Symphonia Domestica and the Heldenleben. But not yet Ariadne auf Naxos, and this a test, a good test for a good orchestra, with only 36 musicians, to try out a full sound but a chamber music sound. We will do it in 1994. I hope I can find the right way

Watch Sawallisch conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra in the rumbustious finale - family quarrel and reconciliation - of Strauss's Symphonia Domestica

How do you work in rehearsal? Do you talk much?

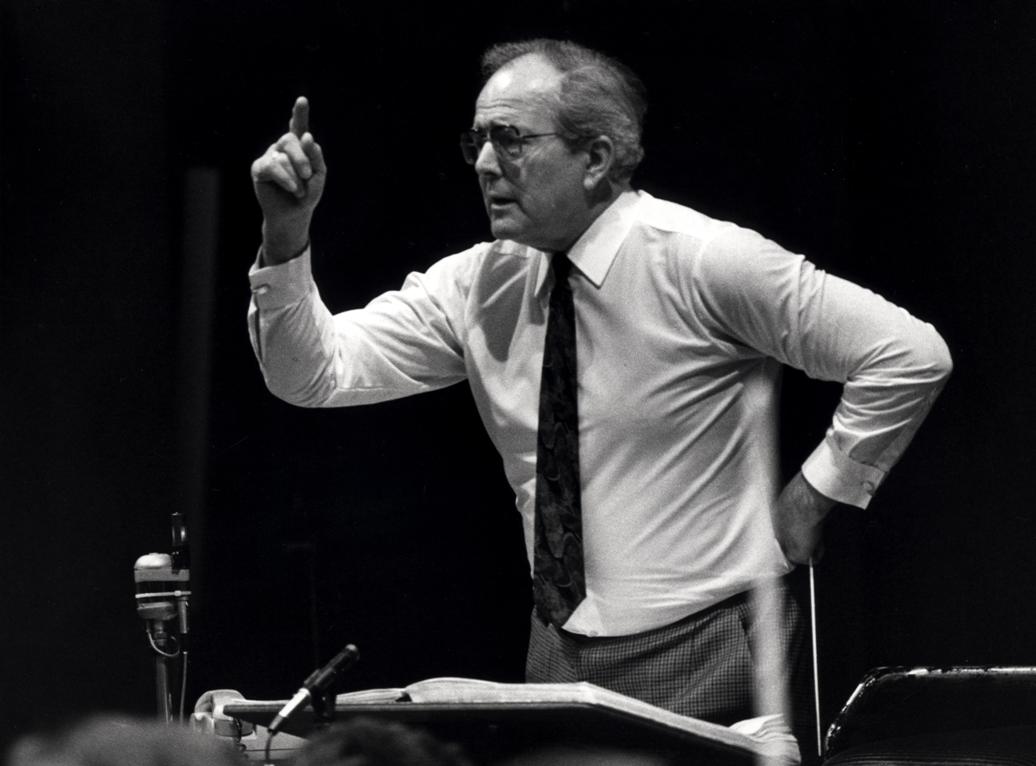

No, I let the orchestra play (pictured near the top of the page, Sawallisch at a recording session). And only some few remarks, only in the words about the situation, when the piece was written. And this is very helpful for the musicians, to sometimes understand why for the composer – not only Strauss - a situation is such. Strauss's music is very different from Schumann's, which has sometimes crazy moments with very short ideas, so very often the context helps.

Do you do that at the beginning?

During. If a point arrives, which no one knows about, then in that time I take the liberty of two or three minutes to explain it.

[We discuss the problems of the old Philadelphia theatre-turned-concert hall's acoustics at length and Sawallisch's hopes for a new hall by the late 1990s]

They say in Philadelphia there’s been a big change from Muti’s approach and repertoire.

For me It’s due to age. I know I can’t stay 15 or 20 years with the orchestra. Muti stayed for 12 years, and 10 as music director, and for me I certainly have six to eight years at maximum, you understand [he managed 10]. Of course I will try, and I told the manager and the director of the orchestra my ideas: if the orchestra chooses me as music director, I would like to study with the orchestra and work with it on the really great world symphonic pieces of the classical and romantic repertoire. This is certainly for each musician of the orchestra the repertoire which is the reason why the musician took up his or her profession as player. It’s certainly not Luigi Nono or John Cage but it is the big music of Schubert, Brahms, Bruckner, Beethoven, Mozart, Strauss and Wagner. And I will try to study the repertoire with the orchestra as fast as possible Brahms symphonies, the nine Beethovens, the four Schumanns, Strauss symphonic poems, to have always immediately in repertoire when we have concerts of the normal subscription series, sometimes in a festival, sometimes when we have only one rehearsal or no rehearsal – and the orchestra is used to performing concerts more or less without rehearsal, but we must have a repertoire together. I must know in which point I can help the orchestra. And it is certainly important for me to work as quickly as possible and make a repertoire of 15-20 pieces as good as possible.

Do you always study the great scores afresh? You recorded quite a few for EMI in the 1950s and 1960s, and then there was a long gap.

You can forget the Fifties and Sixties!

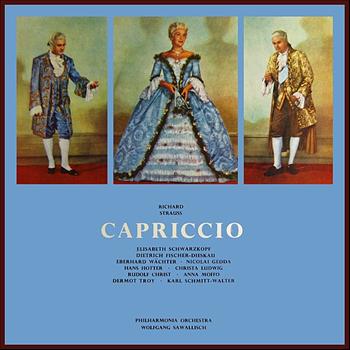

Even the recording of Strauss's Capriccio (original cover pictured right)?

Even the recording of Strauss's Capriccio (original cover pictured right)?

No, except the Capriccio. This is really a good recording. There are a Tannhãuser, even a Flying Dutchman which are not bad.

So why do you say you can forget them?

I think it’s the progress unbewüsst – the unconscious development of my age. And this makes it very difficult for me to record Brahms or Beethoven symphonies, because always immediately after the last minutes of recording I knew that now I can’t change anything because time’s up and only the engineer makes the cut of all precious takes.

Do you have a decision in that?

Yes, more or less, but you understand for me in studio production you can never be so free as you can do in a concert performance. You must do three, four, six times the same eight bars, and always the music dies away, because always there’s less spirit. But in a concert performance you have one time, you can give everything. And in 80 per cent of all recordings if I listen to the recordings we did of the last three or four days, always I’m unhappy because always I would like to change this phrase, the ritardando is not good for me, and then crescendo is not enough, I’m never happy not to have the possibility to retake. And later on you have black and white, or white and white with the CDs, and you’re unable to change.

Do you prefer long takes?

Yes, whole movements. It is my wish in the end and I decided with the engineers and the producer that we do one movement of a Brahms symphony without interruption, and then a second and perhaps a third take, and then he must take out the best pieces. And sometimes there are a few bars we have to retake for technical reasons. But I don’t like to stop too often. It should be one line.

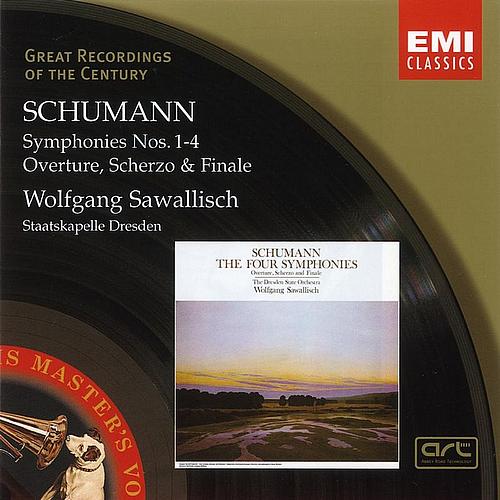

That seems to be obvious in the case of the Schumann symphonies you recorded with the Staatskapelle Dresden in the 1970s

I was very happy with those Schumanns. We had a marvellous help in the person of the musical producer. He is a conductor himself, and we worked together marvellously. And these four symphonies are good recordings, yes. But such a long time ago.

I was very happy with those Schumanns. We had a marvellous help in the person of the musical producer. He is a conductor himself, and we worked together marvellously. And these four symphonies are good recordings, yes. But such a long time ago.

And you haven't recorded much Schumann since.

I like Schumann’s music greatly and I would like to record more of his big choral works. I have conducted the Requiem, the big mass, for Mignon, the Scenes from Faust, Paradise and the Peri, Das Glück von Edenhall, Der Rose Pilgerfahrt: marvellous pieces and none of them much done. I was amazed to find that The Seasons of Haydn is never performed in Philadelphia, and it is a miracle. I will do it.

There's a Hindemith centenary coming up [in 1995], and I believe his music is important to you.

Yes, I feel he's underperformed. Everyone has tended to label him a German composer. But it’s not true. Little by little he became an international composer with great own ideas and a musical language of absolutely personal touch.

Maybe perception of his Gebrauchsmusik [Utility Music] has overshadowed the rest?

My dear Mr Nice, why not? Even Gebrauchsmusik can be good music.

Oh, I agree…

I like all the symphonic pieces, concertos, the Requiem of 1946, a lot of good music. And the first version of [the Hoffmann fantasy-opera] Cardillac in 1926, that was a wild period of composing for him.

Do you still conduct a lot of Carl Orff's music?

I appreciate it very much. But it’s so difficult, nothing much gets done except Carmina Burana, the piece is performed to death, from South Africa to the North Pole, in America and Japan. That's a fantastic testament to the quality of the piece, but it’s only an hour long. I like the three Greek tragedies – it’s a revival of the old Greek theatre but in a much more modern sense, but with long a cappella choruses, long unaccompanied narratives from the singers, long lines and rhythmic accompaniment of the orchestra.

On stage the [Sophocles] trilogy is an incredible success. I remember we did in 1975 a futuristic production of Antigone by Gunter Rennert. It’s like a criminal report: breathtaking, fantastic! But to hold this production on stage for a long time… You can do that with Walküre and Meistersinger and Zauberflöte, you can stop for half a year and you can bring them back without rehearsal. But with these difficult choral works and long entrances of orchestra after a long break – boom! This is so difficult. And after one season's rest of such a piece you need at least three rehearsals to bring it back for a revival to have the same intensity, clarity and perfection, this music must be played really perfectly. And this is impossible in a repertoire theatre where there’s every night another piece, you have no time to study three, four days only for a revival of one performance, that’s impossible. And this makes it so difficult to hold alive these great opera works written by Orff. It’s one of the reasons why these pieces are performed so seldom.

Any chance of a "Greek revival"?

The performing possibilities are too hard. I always asked Orff, I said, my dear Carl Orff, only once in your life write a symphonic piece or a smaller piece for chorus and orchestra, not always this big drama, and he said, no, I can’t write for orchestra, I only can write for love and for dramatic situations on stage! I said, write me an overture of eight to 10 minutes to start a concert. I would like not always to start with Euryanthe, Fidelio, Leonora no. 3, can we have a Carl Orff introduction? No, I won’t, he said. And he never did.

You mentioned not rehearsing certain Wagner operas, but presumably a Ring cycle needs special preparation each time?

Of course, after an absence of the Ring from the repertoire for four or five years, you must study with new singers, a new crew, new staff and new members of the orchestra, young people come in every year and old ones go out. But for instance in 1987 we had a new production of the Ring and since then every year we do two cycles, only eight performances, one cycle in the autumn and one in the spring, and we always talk about the Autumn and Spring Rings, and absolutely without rehearsals. Of course it’s difficult because the National Theatre (interior pictured above) is closed now, and last year without the Ring made it difficult for the season 1993-4, they must repeat and study, and we lose a lot of time for rehearsals. But usually I refused to rehearse. And the concentration of the orchestra in the theatre is so immense, so big, so great. And always it has the intensity of a new creation. If you rehearse beforehand, everyone knows, so we had a good rehearsal, it worked very well so tonight…Without, each player is much more interested to do it as well as he can, and the players practise themselves.

Of course, after an absence of the Ring from the repertoire for four or five years, you must study with new singers, a new crew, new staff and new members of the orchestra, young people come in every year and old ones go out. But for instance in 1987 we had a new production of the Ring and since then every year we do two cycles, only eight performances, one cycle in the autumn and one in the spring, and we always talk about the Autumn and Spring Rings, and absolutely without rehearsals. Of course it’s difficult because the National Theatre (interior pictured above) is closed now, and last year without the Ring made it difficult for the season 1993-4, they must repeat and study, and we lose a lot of time for rehearsals. But usually I refused to rehearse. And the concentration of the orchestra in the theatre is so immense, so big, so great. And always it has the intensity of a new creation. If you rehearse beforehand, everyone knows, so we had a good rehearsal, it worked very well so tonight…Without, each player is much more interested to do it as well as he can, and the players practise themselves.

So nothing - not even a final rehearsal?

Nothing. Of course with the singers I have a piano rehearsal. But only one. An unrehearsed Walküre, believe me, after a year's absence from the house is better than a performance after three, four, five rehearsals. So concentrated. It’s wonderful. Meistersinger too [big laugh] I will record Meistersinger in the second half of April: we have two weeks to do it for EMI, a real studio production. But even for this we decided to make 20, 25 minutes without interruption, or else a complete scene even with mistakes.

Your Ring is filmed live for video, but not for CD [a CD version has recently appeared].

CDs we cannot do, it's not allowed. Because a few singers like Behrens, Kollo, Moll are blocked by previous recordings. This is filmed as a live performance. We recorded two cycles, completely different, but with the same cast and with audience. From the best, one master tape is made. It is a pity you have not seen the laser disc, you need high definition screen to bring out the special qualities [laser discs - remember them?]

Would you be happy with just the sound recording?

85 to 90 per cent, yes.

Would you do a live sound recording here?

The time has passed. Never again the Ring. Meistersinger I will do now and it’s enough.

For a new production on stage I work very closely. And sometimes I ask him to change his idea if I’m convinced the singers' acting on stage is not congruent with the orchestra in the pit. I have always very good connections with directors and we speak frankly about problems. Sometimes the director even asks me if I will change a tempo if he feels it is a little too fast or too slow, 90 per cent of conductors are too slow and he doesn’t know how to fulfil the slow tempo with actions. I often ask directors to have a little more confidence in the music. Sometimes even a period of five minutes without action on the stage works very well if the music is strong enough. No, but I always give the director priority to explain what he’s feeling, and he explains that, and it’s very nice.

Did any of Lehnhoff's thinking change the way that you intellectually thought about the Ring?

I agreed with 90 per cent of what he did. I liked the Rheingold very much, the idea to do the whole setting in a satellite station. It’s not a bad idea. Because how can you demonstrate long after all our science about planes, walking on the moon, where Wotan should live as a god? On the earth he cannot, underground with the Nibelungen he cannot, on the heights now he cannot; where are the gods living? It’s difficult to explain. Now on earth doesn’t exist one mountain, even the biggest ones, where man was not on the top like a god. No-one found a god on top of Everest or Nanga Parbat. So there I agreed with Lehnhoff. I accept Walküre acts 2 and 3. I accept the Siegfried - a very good solution, even Act 2 with the big dragon. And all these different ideas I can accept. And when I look at the scene on stage after three or four or five times I find more new good points

The only thing I have never agreed with Lehnhoff over is the very end of Götterdämmerung. I understood his idea to start with nothing in Götterdämmerung and to go through the centuries very fast until the last technical end of our times. This is a very fast development but I agree. And maybe even there isn’t a solution. He didn’t find the right solution. I confess I personally don’t have an idea how to do it. It is so difficult. And of course Lehnhoff finishes with the atom bomb and after all the deaths, and Alberich [the arch villain of the Ring] is the only figure to survive. Alberich is synonymous for the back world, the minus-creature. And he survives. But the music gives a sense of rebirth, singing the same theme of Sieglinde in Act Three of Walküre, the theme of the wiedergeborene [reborn]. It’s a hopeful new beginning.

But how to suggest on stage the collapse of one world and the beginning of a new one? With or without people you need children to continue the generations. How to show that? Even our good Richard Wagner doesn’t know. If you look at the score there is absolutely no indication of how to reach the conclusion of the Ring cycle. The last indication is Hagen pulled down into the depths of the Rhine [actually I believe it's for the men and women on stage to watch Valhalla burning] And next? There is no regeneration? It is difficult. The other direction is a placating vision, a new landscape with flowers – but this is a primitive ending, no good.

I’m never satisfied. I know what people have said, and Munich people are very strange sometimes. I remember the reaction they had to the new production. They didn’t really like it. And I received, not a lot, but about 15-20 letters with very bad words and criticism about the new production. Why this, why that. After four years this feeling completely changed and now especially my staff on stage are so happy to construct this Ring, and it takes half the time now it took in ’87 because everyone is willing to do his best to construct – everyone is delighted to do it! And now I have the same people who wrote in '87 now writing letters saying, pardon me, maestro, but now I have seen each Ring and now I understand the stage performance. Now we have an interruption of one and a half years and certainly this next cycle in the autumn of '93 with another conductor will have a great interest for people, and I’ll be interested to see the reaction.

I’m never satisfied. I know what people have said, and Munich people are very strange sometimes. I remember the reaction they had to the new production. They didn’t really like it. And I received, not a lot, but about 15-20 letters with very bad words and criticism about the new production. Why this, why that. After four years this feeling completely changed and now especially my staff on stage are so happy to construct this Ring, and it takes half the time now it took in ’87 because everyone is willing to do his best to construct – everyone is delighted to do it! And now I have the same people who wrote in '87 now writing letters saying, pardon me, maestro, but now I have seen each Ring and now I understand the stage performance. Now we have an interruption of one and a half years and certainly this next cycle in the autumn of '93 with another conductor will have a great interest for people, and I’ll be interested to see the reaction.

Do you as conductor especially value what Lehnhoff and Chereau and Kupfer do best, this incredibly close relationship of the singers as characters to each other?

Especially for the Ring. I’m proud of what we achieved in ’87. Maybe this is not true of Meistersinger, Lohengrin or Tannhäuser, but I feel every ten years a new Ring is needed in a different style to reflect international, political and economic - and personal- changes. Because this is the greatest musiktheater we have on our stage, in our opera repertoire. And these performances need always a new feeling due to tne circumstances of the time. And certainly in 1997 with the world situation, with a Europe unified or not, with the terrible situation in Yugoslavia and all the critical situation with financial development or not, and foreign peoples in our country, it’s necessary to think in a new style for the Ring. It’s not necessary for Tosca or Bohème. Meistersinger Is Hans Sachs and the 16th century, you can’t change it, and Tannhäuser is Minnesinger of the 13th century without losing the ties to todays p. But in the Ring the music is without definitions or a certain line, its possibilities are endless – and the stage is the same, you must always rethink about the new world situation to bring out the old situation of money, power and lies etc. That’s my idea that at least every 10 years you must make a new production to realize what happens in our days. Always to hold up a mirror to the times.

Listen to Sawallisch's classic Dresden Staatskapelle recording of Schumann's Fourth Symphony

Add comment