First Person: conductor Edward Gardner on some of his questions and obsessions about Mahler's 'Resurrection' Symphony | reviews, news & interviews

First Person: conductor Edward Gardner on some of his questions and obsessions about Mahler's 'Resurrection' Symphony

First Person: conductor Edward Gardner on some of his questions and obsessions about Mahler's 'Resurrection' Symphony

On music that can be 'universal and personal, fragile and grand, all at the same time'

“If a composer could say what he had to say in words he would not bother trying to say it in music.”

“What is best in music is not to be found in the notes.”

With these two quotations from Mahler, I already feel like putting my pen down. I had intended to write about my approach to the upcoming performance of his Second Symphony with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, but the more I thought about words, the more reductive my thoughts became.

Journalists trying to unlock Claudio Abbado’s genius in interviews on Mahler were met a smile, nod, and just “schöne Musik”, “beautiful music”. As ever, he had the right idea - words, sentences can’t begin to express anything of this music. Instead I’ll share some of the questions I face, and obsessions I have, approaching a performance of this Olympian work.

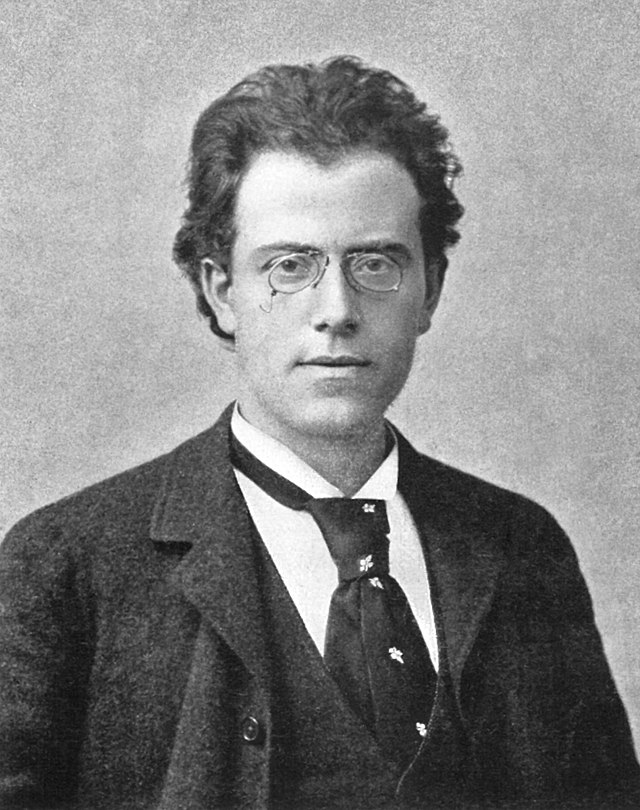

When you observe Mahler the man and composer, you’re met with equal and opposite forces (pictured right, Mahler in 1892). The king of Viennese music, who considered himself an alien wherever he went (and was spat at with racism in that city by chorus members rehearsing his “official Opus One” Das klagende Lied). A man racked by insecurity over life and health, who knew, and proclaimed, that his music would live for eternity. A world-feted opera conductor who never penned one himself; a conducting recluse who would spend the summer in a tiny Alpine hut writing, who adored city life (he wrote of his pleasure being disturbed by a street organ in New York). Extremes and oppositions inform all he was as a musician, and can help us understand how his music can be universal and personal, fragile and grand, all at the same time.

When you observe Mahler the man and composer, you’re met with equal and opposite forces (pictured right, Mahler in 1892). The king of Viennese music, who considered himself an alien wherever he went (and was spat at with racism in that city by chorus members rehearsing his “official Opus One” Das klagende Lied). A man racked by insecurity over life and health, who knew, and proclaimed, that his music would live for eternity. A world-feted opera conductor who never penned one himself; a conducting recluse who would spend the summer in a tiny Alpine hut writing, who adored city life (he wrote of his pleasure being disturbed by a street organ in New York). Extremes and oppositions inform all he was as a musician, and can help us understand how his music can be universal and personal, fragile and grand, all at the same time.

It doesn’t surprise me that the initial reception for Mahler’s first two symphonies was lukewarm, at best. We talk about great composers breaking the mould of history, but in reality, the symphony in the second half of the 19th century still had the same basic shape. From Haydn to Brahms though Beethoven, no matter what shocked audiences or elevated them, the listener would have understood where the piece was inevitably going and felt secure within the form. There are of course outliers to this: Berlioz, Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony, and Bruckner (Mahler was uniquely supportive of Bruckner after the disastrous premiere of his Third Symphony) but no-one before had conceived music of this breadth and scale, reflecting nature, earthly despair, music of the streets, death, and eternity.

We academicise music at our peril - the first tick we give a piece is for its form, structure and unity. Mahler doesn’t fit in the box; he writes feeling first, no matter how long it will take to express and explore it: the anger and desolation of grief, the stillness of a night forest, and at the close of the Second Symphony, the transcendence and ecstasy of an afterlife.

Mahler gives us a gift alongside the Second Symphony: the earlier 20-minute piece Totenfeier, or “Funeral Rites.” This was initially conceived as the first movement of a symphony, and ended as a tone poem with some compromise. Revisiting it in recent weeks gave me a window into the extraordinary development of Mahler’s world by the time, a few years later, he presented the completed symphony. So much of the music, the extraordinary strength of gesture, is transported into the first movement of the Second Symphony, but the differences shine a light. I tried as hard as I could to listen and read Totenfeier with a clear mind, unaffected by what made it into the symphony (almost impossible).

On the page the score looks monochrome, the articulation looks as if it could be written by Brahms or Beethoven, and the phrasing is natural but predictable. Comparing Totenfeier side-by-side with the first movement of the Symphony is revealing. The later score becomes micro-notated, little inflections on individual melody notes, warming the centre of them, yearning shapes in short violin phrases, figures that extinguish themselves, and expressive sliding in the strings. The opening woodwind’s skeletal melody has been given accents on every note, as if written on stone. It’s this concentration of expression that leads us to Mahler’s emotionally-charged palette, the Mahler that completely engages us. (PIctured below by Mark Allan: Gardner working on detail with the LPO)

I think of a poem by Auden whenever I’m in Mahler’s music. I was fortunate to be introduced to it by Britten’s wonderful setting in A Spring Symphony. It’s “Out on the lawn I lie in bed” (“A Summer Night”). It gives me the same feeling of space - youthful love and friendship, framed by the eternity of the stars. But under the surface is the worry of a dissolving society, and the threat of war. Mahler’s threat, in this piece at least, is death - and he suffered a level of personal tragedy that shouldn’t be survivable.

Mahler felt compelled to add narratives to his first two symphonies, to give an access point to his strange new world, which he eventually withdrew with a sense of shamed humiliation. He found words, even in a piece that finishes with text, redundant. I do find something useful in his guide to the second and third movements. He wrote that they form an interlude, reflecting an earthly life, a memory of contentment. Or as Marina Mahler, his granddaughter, so effortlessly put it: “unhappiness remembering happiness”. In the second movement the gentle beauty is invaded time and again by unfulfilled optimism and earthly pain.

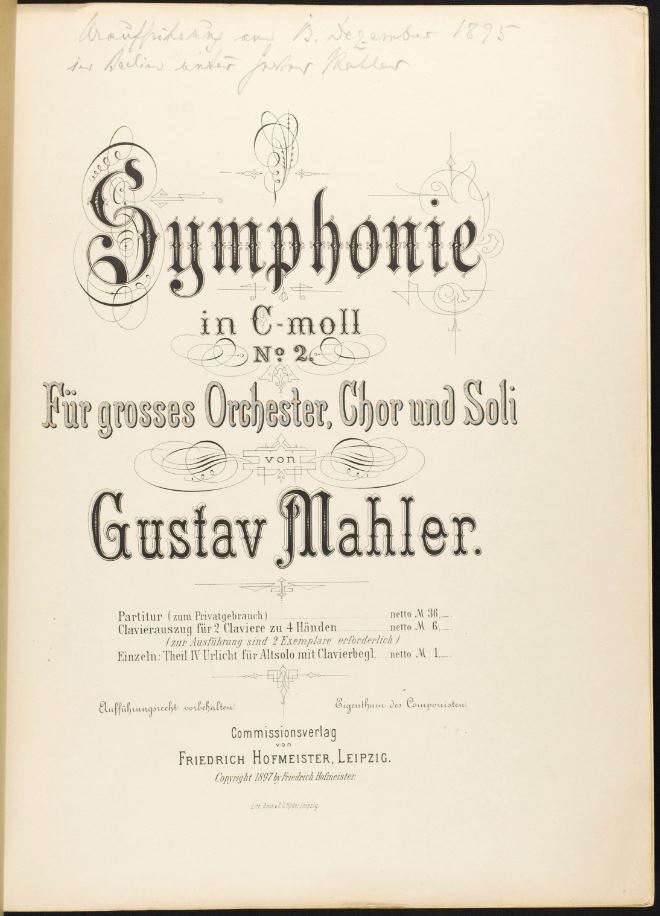

“Urlicht”, primal light, the fourth movement of the symphony, pours balm over the troubled music of the initial movements, and allows us the enormous journey of the last (pictued right, frontispiece of the quasi-folk collection Des knaben Wunderhorn which includes the text of "Uricht").

“Urlicht”, primal light, the fourth movement of the symphony, pours balm over the troubled music of the initial movements, and allows us the enormous journey of the last (pictued right, frontispiece of the quasi-folk collection Des knaben Wunderhorn which includes the text of "Uricht").

But what’s the third movement about? Why is it there? On the surface it is a cheeky, mischievous parable of St Anthony giving a sermon to fishes to behave better - but is there a darker message? The brutality of the death shriek at the end (repeated at the opening of the finale, and at its apex) seems an enormous over-reaction by the saint. Could the movement be a comment on the absurdity of organised religion and hierarchy, broken by that piercing cry? In any case what I’m left with at the end of the piece, despite the religious texts, isn’t a feeling of religious fulfilment, but an overwhelming human joy.

The journey to that end takes us through a Miltonian battle between death and new life, but the sonorities we are left with before the final resolution are closer to our own, shared experiences; off-stage street-music in the background, refusing to let us lift off the earthly plane. Before the final resolution, almost in a cocoon of silence, he gives us a natural, rhapsodic picture; far-off horncalls, answered by birdsong, finally heralding voices, bringing us to final fulfilment. Even at the point of the greatest expression, nature and humanity are all around us, and we’re reminded this piece is for us, here and now.

My access point for conducting Britten (strange he gets two mentions, but he loved Mahler too!) was hearing the latitude he gave his own pieces when conducting. For him, his own obsessively- defined notation didn’t mean less spontaneity or shaping. I feel the same is true of Mahler; rigorous instruction in the score, but he was generous and flexible with others conducting his music. He wanted conductors, with their orchestral colleagues, to find what was right, that evening, in that room with that group of musicians.

I’ve listened to many performances of the Second Symphony recently, more for this article than for conducting the piece. I found it fascinating and ultimately useless. Oskar Fried’s Berlin recording is worthwhile, as we know Mahler went through the piece with him. It’s surprisingly pacey, and the mono sound flattens the interpretation, but I loved the freedom for emotional gesture above ensemble. Our music-making now, at least for the last 70 years, is so tidy, that it’s a good reminder that the feeling must come first.  I expected not to relish Bernstein’s saturated version, but I was left with a sense of wonder at his commitment and resolve, even with speeds I would never approach. I loved the understated fever of Tennstedt with the LPO, and thrilling to hear this orchestra perform, as ever, with such a quality of sound; Mahler is one of their musical homes. Abbado’s recordings from Lucerne are wonderful, a communion between players and conductor after a lifetime of music-making; the unachieved climax in the second movement of Mahler Five is one of the most moving bits of music-making I have ever heard, and his Second has an extraordinary lyric purity. These performances aren’t trees that I can pick fruit from - they’re filled with decisions, space and shaping that work only in their context.

I expected not to relish Bernstein’s saturated version, but I was left with a sense of wonder at his commitment and resolve, even with speeds I would never approach. I loved the understated fever of Tennstedt with the LPO, and thrilling to hear this orchestra perform, as ever, with such a quality of sound; Mahler is one of their musical homes. Abbado’s recordings from Lucerne are wonderful, a communion between players and conductor after a lifetime of music-making; the unachieved climax in the second movement of Mahler Five is one of the most moving bits of music-making I have ever heard, and his Second has an extraordinary lyric purity. These performances aren’t trees that I can pick fruit from - they’re filled with decisions, space and shaping that work only in their context.

With the wonderful musicians of the LPO, our choirs and soloists, this is what I’m doing right now and looking forward to in performance (forces with Gardner pictured above); creating our own context, with these people, in that room, on that night, for Mahler’s all-encompassing world to resonate and overwhelm.

- Performance on 23 September reviewed here

- Read classical music reviews on theartsdesk

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Comments

fascinating & profound,

fascinating & profound, Gardner should be an author as well.

I totally agree. The

I totally agree. The eloquence, and the time he put in to work on the piece, took me completely by surprise. I wasn't going on Saturday evening, but this convinced me I should - and it was exactly for me both as anticipated, and as Rachel Halliburton described it in her review.