Stravinsky: Late Works Cappella Amsterdam, Nord Nederlands Orkest/Daniel Reuss (Pentatone)

In 1952, his 70th year, Stravinsky had a compositional crisis. After completing his biggest piece – The Rake’s Progress – he felt unable to compose and didn’t know what to do. The route to a solution was laid out by Robert Craft, the young American conductor who had been helping Stravinsky with the English pronunciation of The Rake’s libretto. Craft led him to the serial music of the avant-garde – composers like Webern and Boulez – and this provoked the final swerve of Stravinsky’s notoriously circuitous stylistic journey, and allowed him a final 15 years of creativity.

These late pieces have not achieved anything like the success and popularity of earlier Stravinsky – but then again, what else in 20th century music does match up to The Rite of Spring and The Firebird? The late works are for the most part knotty, severe and a bit unfriendly – although always with a distinctively Stravinskian voicing of chords and sense of theatre. I have always found a lot of these pieces hard going, but this new album of mainly vocal works by Cappella Amsterdam and Noord Nederland Orkest under Daniel Reuss presents committed and winning performances which have changed my view of one piece in particular.

Although they are advertised as late works, there are a couple of earlier ones included, which are a bit out of place but point up the continuities across Stravinsky’s work. In particular the Chorale, which became the final section of the Symphonies of Wind Instruments in 1920, is presented here in a version for two harmoniums, and has clear parallels with the instrumental movements of Stravinsky’s final major work, Requiem Canticles. This latter piece is given a fine reading, from the quasi-Venetian brass of “Tuba Mirum” to the stunning bell-infused final movement.

A problem with serialism is that it is fundamentally unsuited to vocal music, with its extreme chromaticism and lack of note repetition, so the vocal and choral passages can be quite ungrateful. The performers here are as good as it gets, but it is still the case that instrumental movements, like the “Dirge-Canons” of In Memoriam Dylan Thomas, or the Double Canon, are more congenial than the sung ones. And I do feel that some of these late pieces fail the Stravinsky quality test, even with these most sympathetic and careful of performances, and would not be remembered if they were by anyone else.

The big revelation for me was Threni, Stravinsky’s first wholly serial piece, which I had always found beyond me. But I clearly just hadn’t heard the right recording, which this is. It is a challenging listen, even here, but Reuss’s choir and orchestra chart a path through it which captures both the hieratic ritual but also the humanity at the heart of this setting of the Lamentations of Jeremiah. It is by turns operatic and proudly extrovert – and suddenly quietly intimate and personal. The album is worth hearing for Threni alone – although the Requiem Canticles is also something I will go back to. Bernard Hughes

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco: Platero y yo – an Andalusian Elegy Niklas Johansen (guitar) (OUR Recordings)

Born in Florence in 1885, Italian-Jewish musician Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco saw his early career as a prominent Italian contemporary composer interrupted by the rise of fascism in the 1930s, Mussolini’s Italian Racial Laws preventing performances of his music and barring him from teaching. Assistance from Toscanini and Heifetz helped him secure safe passage to New York, where he found work in Hollywood and taught privately. Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s list of pupils contains a slew of famous names, including Jerry Goldsmith, Elmer Bernstein, John Williams, Nelson Riddle and André Previn (his personal favourite). His output was huge and varied but he’s best remembered today for his guitar music, most of it composed for his friend Andrés Segovia. Including the work on this exquisitely packaged double album, Platero y yo - a sequence of short solo guitar pieces intendended to accompany the recitation of extracts from a celebrated work by the great Spanish poet Juan Ramón Jiménez. His Platero y yo consists of 138 prose poems describing scenes in the life of the young poet and his beloved donkey. There’s no narration here, the poems instead presented in the booklet with accompanying illustrations by Danish artist Halfdan Pisket.

Eloïse Roach’s English translations read well, Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s selection taking in Platero’s frisky youth, "tender and loving as a little boy", descriptions of the Andalusian landscape and a wide variety of human encounters. The pieces stand up as delicious miniatures on their own terms, but hearing them whilst reading the poetry adds another dimension. Sparrows, butterflies and canaries spring to life, Castelnuovo-Tedesco just as adept when conveying an abstract idea. Two early numbers evoking melancholy and friendship are affecting, and there’s a moving portrait of a consumptive young girl, Platero’s intervention provoking laughter “from her sharp, dead child’s face, all black eyes and white teeth.” Guitarist Niklas Johansen is a magnificent guide, his idiomatic, deft playing enough to convince me that Platero y yo is one of the great instrumental cycles and a 20th century masterpiece. Sample Johansen in Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s description of Platero’s death, his percussive raps on the guitar’s body sounding like hammer blows, before a magical suggestion of sunlight shining through a stable window. Beautifully produced and magnificently recorded, this is a fabulous, life-enhancing release.

Into the Light: Rediscovered chamber music by Christoph Graupner and others Musicians of the Old Post Road (OPR Recordings)

Prolific German baroque composer Christoph Graupner (1683-1760) successfully applied for the role of Thomaskantor in Leipzig in 1722, only for his Darmstadt paymasters to insist that he stayed put, albeit with a pay rise. That Leipzig post went instead to one J S Bach, a musician who Graupner respected deeply. That he’s remained a relatively obscure figure is partly due to his having had relatively few pupils and mostly down to his music being out of circulation, a legal dispute preventing his descendants from publishing it. Boston-based chamber ensemble The Old Post Road make a persuasive case for Graupner’s talents on this disc; I was hooked after hearing their sparky rendition of the Quartet in G Minor for strings and continuo’s dizzying fugal finale, and beguiled by the central “Adagio” of the G major Sonata for flute, harpsichord and basso continuo, baroque flautist Suzanne Strumpf and harpsichordist Benjamin Katz making a three-minute slow movement feel far longer than it actually is, in a good way.

Including three works by contemporaries of Graupner makes sense. A compact Sonata à Quattro in G by his pupil Johann Friedrich Fasch is delightful, though Telemann’s D minor Quartet plumbs greater depths, its restless second movement a highlight. We get a piece composed by Graupner’s Darmstadt patron Ernest Louis, a well-travelled music lover whose little Chaconne, taken from the first of his 12 symphonies, is a charmer. Graupner fittingly gets the last word with an effervescent Concerto for flute, strings and continuo. An enjoyable anthology, nicely engineered.

Moeran: Symphony in G minor, Violin Concerto BBC Symphony Orchestra/Sir Adrian Boult, with Albert Sammons (violin) (Somm)

Naysayers will wonder if it’s worth investigating an album containing mono live recordings of two big works by a composer who’s a small but lovable footnote in 20th century British musical history? In this instance, most definitely: if you’re fond of Holst, Elgar, Vaughan Williams, Walton and/or Sibelius, you need to hear Ernest John Moeran’s Symphony in G minor. Moeran (1894-1950) led a short but eventful life, his compositional career impeded by a head injury sustained on the Western Front in 1917 and chronic alcoholism. Moeran divided much of his time between County Kerry and East Anglia, befriending the young Benjamin Britten along the way. Stephen Lloyd’s interesting booklet essay includes Britten’s memories of the older composer, describing him as “a near-invalid, broken by the 1914-18 war… (who) produced music of personality and beauty.”

The protracted gestation of Moeran’s large-scale, four-movement work recalls that of Walton’s Symphony No. 1; commissioned in 1925, it was only completed in 1937. Moeran wasn’t keen on the idea of Adrian Boult handling the first performance (Leslie Heward and the LPO gave the premiere in 1938), though Boult’s luminous 1975 recording on the audiophile Lyrita label remains a cult classic. Moeran did attend the 1950 concert where the performance on this disc was taped, acknowledging that “Boult rose to the occasion and gave it a fine performance, really good”. Superbly restored by Lani Spahr, it sounds more than decent here, Boult securing excellent playing from the BBC Symphony Orchestra. Tempi, slightly swifter than the 1975 LP, are nicely judged, Boult catching the ebb and flow of the first movement’s beautiful second subject. The overlapping rhythmic patterns are seamlessly co-ordinated, the closing chords suitably brusque. If there’s a more distinctly English-sounding symphonic movement out there, I’ve not heard it. The rest of the symphony reflects Moeran’s love of Sibelius, the finale’s climax recalling Tapiola, and the ending, as with Walton 1, referencing the coda of Sibelius’s 5. No matter – this is a gorgeous, lovable work that really deserves to be better known.

Moeran’s 30-minute Violin Concerto, though attractive, doesn’t scale the same heights. Somm give us another live recording, Boult and the BBC SO accompanying the great Albert Sammons. Initially reluctant, he was persuaded by Moeran to take up the piece and this 1946 performance in Norwich was his last public concerto performance. The work feels overstretched but the “Lento” finale is sweetly done, and there’s no audible sign of the Parkinson’s disease which prompted Sammons’ retirement. Get this disc for the symphony. The digital download includes as a bonus a live recording of Moeran’s Cello Concerto, played by his wife Peers Coetmore.

Constellations: Ravel, Barber, Shostakovich Ensemble Ouranos (Alpha-Classics)

Ravel arranges well for wind quintet. This I knew from the 2013 album by the Orlando Quintet, which featured delightful and very effective arrangements of his Mother Goose Suite, Sonatine and, most surprisingly, the String Quartet. The French group Ensemble Ouranos were clearly taking notes, as their new album Constellations not only turns Le Tombeau de Couperin into a quintet, but makes a success of a string quartet I instinctively felt wouldn’t work in this instrumentation: Shostakovich’s Eighth.

Le Tombeau de Couperin, originally for piano and later orchestrated, commemorates friends of Ravel’s who died in World War I, through the unlikely lens of the keyboard suites of François Couperin. The clean lines and crystalline harmony of the original make it promising material, and arranger Mason Jones does a good job. The skittish runs of the “Prélude” work beautifully and are played with a fitting fleetness. In the “Fugue” the contrapuntal lines emerge gracefully and the “Menuet” is a stately dance that is very reminiscent of Mother Goose. The “Rigaudon” rounds things off with a fizzing tempo and pungent bassoon. The only shame is that there are only four movements here – the brilliant “Forlane” and final “Toccata” are absent. I’d have loved more. Instead we get the early Pavane pour une infante défunte, also first written for piano, also well arranged, this time by Guy du Cheyron. It has a beautiful tune, which keeps coming back, but I found it a bit statuesque, and feel it needs to move forward more.

Samuel Barber’s Summer Music, which I didn’t previously know, is the only piece on the album conceived for wind quintet. It lives up to its name in a languid, dreamy first movement, the music getting faster through the two subsequent movements, the second like a chase scene and the third a restless dance – before the “indolent” spirit of the opening returns. It’s played with bounce and joie de vivre throughout and is very different in tone from what follows.

Shostakovich’s autobiographical Eighth Quartet was written at the nadir of his depression at persecution by the Soviet authorities. It was composed at lightning speed and it feels perfectly conceived for strings (it is also known in a string orchestra version). So it seemed unlikely material – but actually works a treat. The opening movement, with its long sustained lines, needs to be taken faster than most string quartets ever would, and even then requires superhuman breath control by bassoonist Rafael Angster to get through the long, long held notes. But hearing the vulnerable second subject on the flute makes total sense, and the infernal dance of the second movement has a real punch, the klezmer episodes sounding even more at home with the tune on clarinet and horn than in the string original. The arrangement, by David Walter, is extraordinary, all the more so for having such tricky material to work with, and I loved it. The last two movements are both slow, as the music descends along with Shostakovich’s mood. The bleakness of the low bassoon, horn and clarinet sounds utterly desolate, only for little pockets of brightness to bubble up and bubble back down again. Highly recommended. Bernard Hughes

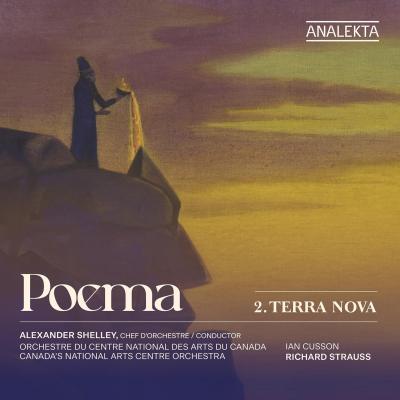

Poema 2: Terra Nova Orchestra du Centre National des Arts du Canada/Alexander Shelley (Analekta)

Here’s the second volume in conductor Alexander Shelley’s ongoing series of albums coupling Strauss tone poems with newly commissioned pieces from Canadian composers. Get past the confusing title and there’s lots to like here, Shelley and his excellent Ottawan orchestra understanding that one big challenge with Strauss’s Also sprach Zarathustra is to make the music which follows the spectacular sunrise not feel anticlimactic. That opening is brilliantly done here, a rumbling organ pedal preparing the ground for the solo trumpet’s ascent. You can really hear the orchestra’s answers growing progressively louder and richer, and the moment where the C major organ chord drops falls away is rightly disorientating, Shelley’s juddering cellos and bases diving in before Strauss’s gorgeous hymn takes shape. This is an entertaining performance with a thrilling, craggy fugue in the “Of science” section and a waltz which never takes itself too seriously. Shelley makes the final “night-wanderer’s song” feel like a fitting coda, the loose ends almost but not quite tied up.

It's coupled with Ian Cusson’s 1Q84: Sinfonietta Metamoderna, inspired by a Haruki Murakami novel. Concise and colourful, it left me baffled; Cusson’s sleeve note offers a detailed synopsis of the novel and little else, leaving me wondering how his detailed four-paragraph summary of a very long book could possibly be condensed into a ten-minutes of music. Best to crank up the volume and enjoy the work as a sparky curtain raiser for the Strauss. This album lasts just 44 minutes – surely room could have been found for more music?

Add comment