Kudos, as ever, to Vladimir Jurowski for making epic connections. Not only did he bookend a rich LPO concert with two very different symphonies from the late 1930s by Stravinsky and Shostakovich; he also masterminded and attended the early evening special event, another variegated shell in the cornucopia of the Changing Faces: Stravinsky's Journey festival.

Featuring the young players of the orchestra's Foyle Future Firsts programme and their mentors, it started with a lovable performance of Stravinsky's Dumbarton Oaks Concerto - exactly contemporary with the Symphony in C heard later - springily conducted by Tim Murray and followed up with short trio-memorials to and by the master. The weird finale was Kagel's Fürst Igor, Strawinsky, a crazy monologue to a text from Borodin's opera for bass (young but already impressive Royal College of Music student Timothy Edlin) and eclectic small forces.

It would be tempting to say that the full-bodied performance of Shostakovich's mighty Sixth Symphony at the end of a generous evening stole the limelight. Certainly the razor-sharp articulation of the two mad movements which follow the tragic opening Largo and the sheer brilliance of the chameleonic soundscapes put this up in the league of the composer's greatest interpreter, Yevgeny Mravinsky. But you could also see it as the last bid for a gold medal of the LPO's sensational woodwind department, working beyond the call of duty throughout a spellbinding evening.

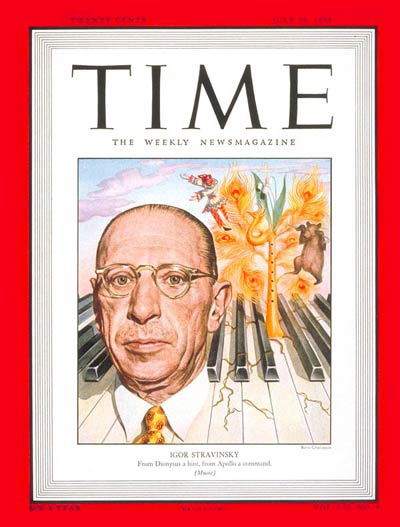

Just how elaborately and freshly Stravinsky writes for them in his Symphony in C, with its concertante second movement, shone especially in oboist Ian Hardwick's elegant twists and flourishes, his cool duet with colleague Alice Munday at the heart of the work, and later in characterful bassoonist Jonathan Davies's leading the grave low-register chorales of the finale. The symphony's insouciance is deceptive: those minor thirds earlier favoured in Oedipus Rex and Perséphone help poise the argument between darkness and light. And how much darkness there was in Stravinsky's life at the time of his move from France to America; in 1938 and '39 he lost his first wife, mother and daughter to the tuberculosis which also forced him into a sanatorium before he headed for a new life in the USA (pictured above: the composer honoured by Time magazine 10 years later).

Just how elaborately and freshly Stravinsky writes for them in his Symphony in C, with its concertante second movement, shone especially in oboist Ian Hardwick's elegant twists and flourishes, his cool duet with colleague Alice Munday at the heart of the work, and later in characterful bassoonist Jonathan Davies's leading the grave low-register chorales of the finale. The symphony's insouciance is deceptive: those minor thirds earlier favoured in Oedipus Rex and Perséphone help poise the argument between darkness and light. And how much darkness there was in Stravinsky's life at the time of his move from France to America; in 1938 and '39 he lost his first wife, mother and daughter to the tuberculosis which also forced him into a sanatorium before he headed for a new life in the USA (pictured above: the composer honoured by Time magazine 10 years later).

The first movement is perhaps Stravinsky's only successful exercise in symphonic form; the kaleidoscope from the more familiar Symphony in Three Movements then takes over until the three-note figure returns to close the argument. It needs crispness, attack and elan, not easy qualities to combine, but Jurowski offered them all in a totally engaging interpretation which may help to give this underrated, enigmatic but always intriguing work new life.

Woodwind-wise, it was then clarinets to the fore in the bizarrely-orchestrated 1953 version of the 1940 Tango for piano. Brass ensemble, solo guitar and solo strings lend piquancy and at one point the whole group sounded like a giant bandoneon - an easy evocation for a composer who had conjured a massive orchestral accordion in the fairground music of Petrushka. The short piece meant major platform rearrangement; but if Jurowski didn't insist on its inclusion, how would this oddity ever be programmed otherwise?

Woodwind-wise, it was then clarinets to the fore in the bizarrely-orchestrated 1953 version of the 1940 Tango for piano. Brass ensemble, solo guitar and solo strings lend piquancy and at one point the whole group sounded like a giant bandoneon - an easy evocation for a composer who had conjured a massive orchestral accordion in the fairground music of Petrushka. The short piece meant major platform rearrangement; but if Jurowski didn't insist on its inclusion, how would this oddity ever be programmed otherwise?

Admittedly it can't move so easily as the piano original, which always-thoughtful Leif Ove Andsnes (pictured left by Özgür Albayrak) gave us as a spry encore to his not so rewarding role in Debussy's Fantaisie. It was the French composer who commented of Stravinsky's The Firebird "You have to start somewhere"; and his 1889 "somewhere" is less exciting, the free flow that would reach its apogee in La Mer carried along by less distinguished ideas, the piano merely bubbling along with the orchestra. The woodwind again shone in their lion's share of pastoral themes, and between them conductor and pianist whipped the finale into a Bacchic ecstasy, but given the material it was still a simulacrum rather than the real thing. Anyway, that's the work ticked off in concert for the centenary year of Debussy's death.

The Shostakovich took some adjusting to after the first-half array; its tragic lines even felt a little old-fashioned after Stravinsky's pioneering work, for all their unison resonance, and it wasn't until we got to the desolate flute solos of Juliette Bausor - peerless among London principals - that the first movement really began to get under the skin of this listener. How Bausor and her piccolo colleague manage to make their later rapid flights sound as one was only one of many sonic miracles as the Largo's two headlong successors in Shostakovich's typically quirky symphonic sequence captivated, terrorised and overwhelmed an astonished audience. A potent reminder, too, that whereas we once thought Shostakovich took the lunacy of his times to satirical extremes, we now see that craziness as an accurate reflection of our own.

Add comment