Charles Saumarez Smith: The Art Museum In Modern Times review – the story of modern architecture | reviews, news & interviews

Charles Saumarez Smith: The Art Museum In Modern Times review – the story of modern architecture

Charles Saumarez Smith: The Art Museum In Modern Times review – the story of modern architecture

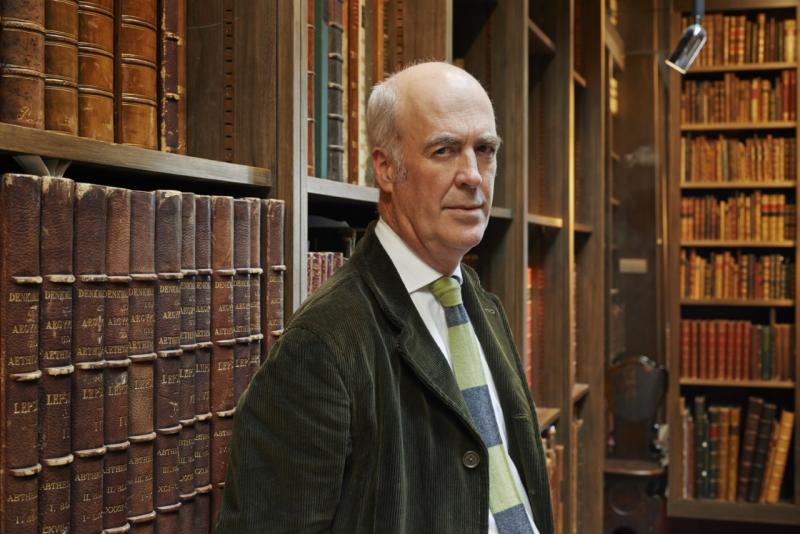

Former director of London's National Gallery explores recent architectural achievements

“This book is a journey of historical discovery, set out sequentially in order to convey a sense of what has changed over time.” Add to this sentence, the title of the work from which it is taken, The Art Museum in Modern Times, and you’ll probably have a reasonable sense of Charles Saumarez Smith’s latest book. Simple, effective – Smith presents us with a series of case studies of museums, placed in chronological order according to each’s unveiling.

In this journey, it is Smith who performs the role of the museum guide. As a former director of London’s National Portrait Gallery, National Gallery, and Chief Executive of the Royal Academy of Arts, it is one for which he is more than qualified. The discussion of each museum, beyond “its construction, who was involved and what they wanted to achieve” – architects, yes, but also directors, private donors, and Saudi princes – is instilled with Smith’s first-hand experience of each museum. With this, comes a largely predictable line-up. The icons of New York, Paris and London all feature, but there is still room for those perhaps further afield, from the São Paulo Museum of Art (1969), “a long, gigantic, rectilinear concrete block, like a skyscraper tipped on its side”, to Naoshima’s tranquil Benesse House Museum (1992), or the Muzeum Susch (2019), tucked away amid Switzerland’s Engadin mountains.

With informed and engaging prose, Smith brings out the personality unique to each museum. This is complemented by a diverse selection of images: portraits of Alfred H. Barr Jr, first director of the Museum of Modern Art, and Gae Aulenti, designer of the controversial Musee D’Orsay (1986); sketches belonging to Renzo Pianzo, architect of The Menil Collection, Houston (1987), or David Chipperfield’s competition entry for the Hepworth Wakefield (2011); and photographs, elucidating even the more complex, most idiosyncratic design features – such as the staccato staircase of David Walsh’s MONA, Hobart (2011), or the “white, organic, plastic skin” enveloping Los Angeles’s The Broad (2015). All these play their part in a book that is, above all else, shockingly good-looking – which, given its concern more with the buildings that house works of art than the works of art themselves, seems only fair to mention. Smith warns, “Museums are becoming ever more commercial and looking ever more like shopping malls”. If so, the folks at Thames & Hudson are ahead of the game. This is proper coffee-table stuff, a lesson in minimalist product design, and the kind of book which, in a superficial sense at least, you need to own.

With informed and engaging prose, Smith brings out the personality unique to each museum. This is complemented by a diverse selection of images: portraits of Alfred H. Barr Jr, first director of the Museum of Modern Art, and Gae Aulenti, designer of the controversial Musee D’Orsay (1986); sketches belonging to Renzo Pianzo, architect of The Menil Collection, Houston (1987), or David Chipperfield’s competition entry for the Hepworth Wakefield (2011); and photographs, elucidating even the more complex, most idiosyncratic design features – such as the staccato staircase of David Walsh’s MONA, Hobart (2011), or the “white, organic, plastic skin” enveloping Los Angeles’s The Broad (2015). All these play their part in a book that is, above all else, shockingly good-looking – which, given its concern more with the buildings that house works of art than the works of art themselves, seems only fair to mention. Smith warns, “Museums are becoming ever more commercial and looking ever more like shopping malls”. If so, the folks at Thames & Hudson are ahead of the game. This is proper coffee-table stuff, a lesson in minimalist product design, and the kind of book which, in a superficial sense at least, you need to own.

What this is not, is a radical interrogation of the dynamics of power that have made, and that still make, all this possible: the dependence of museums on vast, often dubious sources of wealth; the ethics of restitution; and the lingering questions as to what role museums and galleries might play in the ongoing fight against racism. Excepting a few politically-minded case-studies, only in Smith’s brief concluding statement do these issues seriously threaten to emerge. Museums themselves might well have moved on from the so-called modernist dream of an unadorned, blank-slate gallery, but in its unperturbed aestheticism The Art Museum of Modern Times is about as white-box as they come.

Good. No book can exhaust the full extent of a topic, and there are others (perhaps none more so than today) willing to do the dirty work. Arguably, even, there is a bravery in the blinkered view. Museums, in the real world, are struggling to stay open; Smith’s book is a celebration of exactly what has been missed. Its readers may face the opposite problem.

- The Art Museum In Modern Times by Charles Saumarez Smith (Thames & Hudson, £30.00)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Add comment