Alan Warner: Kitchenly 434 review – dreams and delusions in the backwaters of fame | reviews, news & interviews

Alan Warner: Kitchenly 434 review – dreams and delusions in the backwaters of fame

Alan Warner: Kitchenly 434 review – dreams and delusions in the backwaters of fame

A bittersweet comic idyll from the last days of prog-rock

“They think it’s all drugs and sex up here, Mrs H.” “Bless me.” The reality, at Kitchenly Mill Race, runs more to a nice pot of Tetley’s and a plate of Gypsy Creams. But “people are funny around famous folk”. At this Tudor manor house in Sussex – boldly enhanced in the 1930s by an Arts-and-Crafts wing – resides none other than Marko Morrell, lead guitarist of prog-rock legends Fear Taker.

Once thin on the ground, rock’n’roll novels now silt up publishers’ lists like marked-down concept albums in a retro vinyl store. For his ninth book, the Scottish author of The Sopranos and Morvern Callar has not only thrust his spade lustily into the soil of a Deep England poised uneasily between myth and modernity. Alan Warner has niftily shifted rock fiction’s usual angle of vision. In place of the expected “excess all areas” arc of ascent and decline, hubris and nemesis, we experience just the plush and becalmed backwaters of stardom. Marko himself, that cannily business-minded and (so far as we know) genuinely gifted axeman from suburban Sutton, only surfaces as an unseen temporary presence, or disembodied telephonic voice. Fear Taker’s rapid rise from pub circuit to stadium glory in the Seventies heyday of grandiose “progressive” bands exists merely as a rumour that echoes through Crofton’s scrappy memories. In the present, he worries a lot about those New Wave barbarians, finishing off the dethronement of the Moog-and-Fender epic style that punk has begun. In secret, though, he enjoys even Gary Numan, and furtively tunes in to John Peel’s New Wave-partisan radio show as if “in occupied France listening to a wartime broadcast on the BBC”.

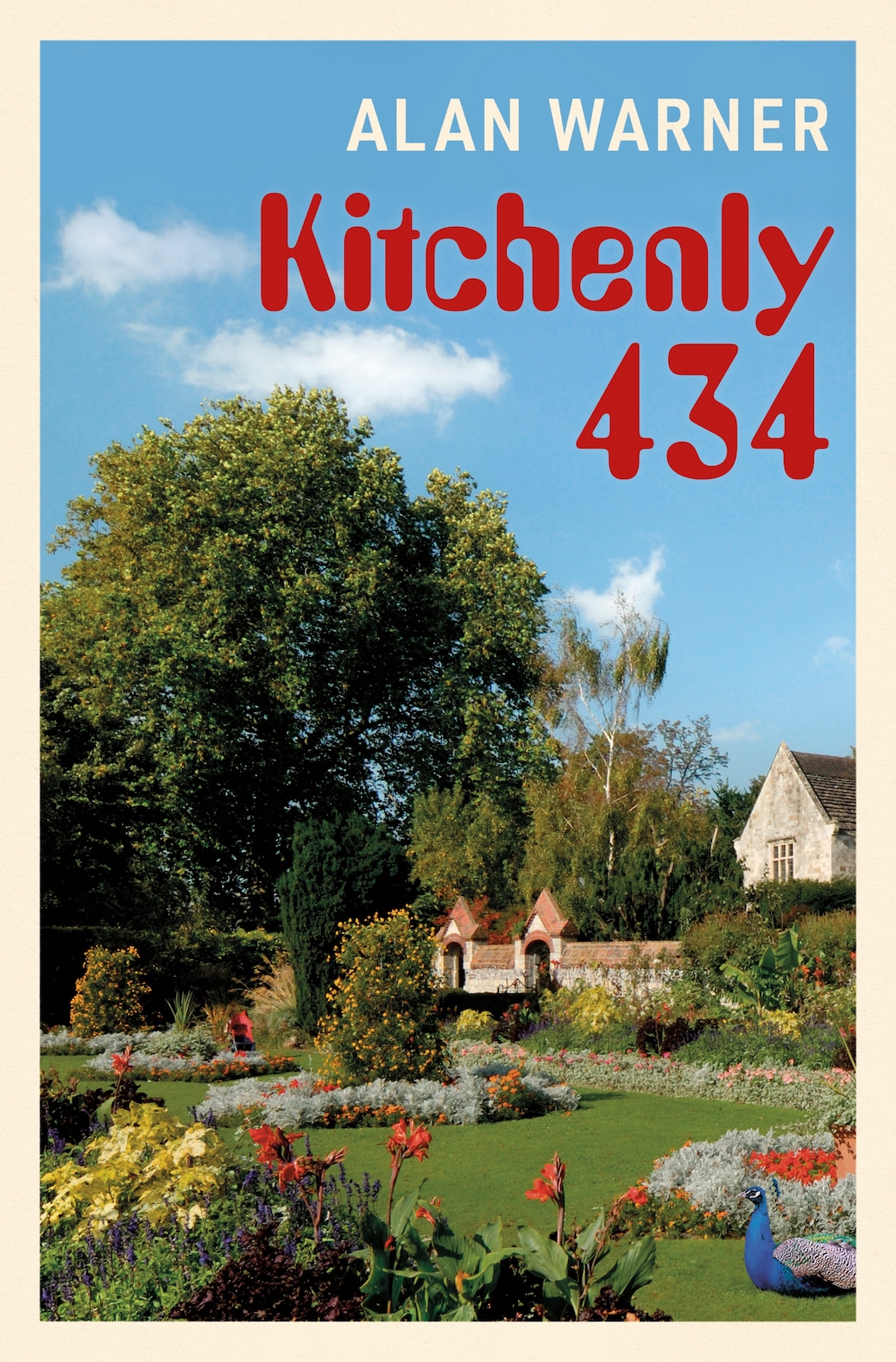

For the moment, in this blue dawn of Margaret Thatcher’s premiership (Marko, of course, voted for her), there’s scarcely a cloud on the hilly horizon beyond the Kitchenly estate. The moated main house sits, flanked by a pair of converted mills joined to it by airport-style covered walkways, within its “paradisal compound of dolorous laburnum and lavender banks which scent the decorated interiors when the summer manor windows are fixed open on their ornate securing-arms”. Especially at the outset (a proper tour de force), Warner lets Crofton turn up the Brideshead amp to 11. Someone must surely have wanted to call this book Motörhead Revisited. The entire performance wavers playfully between an insolent piss-take of the English country-house novel, and a wryly nostalgic hommage. Since, until the very end, not much happens while Crofton potters through his sunlit Sussex days, littered with comic mishaps and rather more disturbing fantasies, everything here depends on his voice – and what the reader makes of it.

Yes, he’s a self-deluding wally, the most needy and cringing of unreliable narrators. He embroiders his history with Marko (“with me he can count on honesty and clarity”), bigs up his own menial house-minding role, and pursues his feud with grizzled gardener Dan Mullan, who brings a feral whiff of “tied cottages and bestiality”. Worse, the jumped-up janitor nurtures fantasies about willowy Natandra, just turned 16 and living with her Stevie Nicks-lookalike mum Abigail in one of the new bungalows built on a strip of Marko’s land. At various points, you half-expect Warner to steer the story of Crofton (who, back in 1979, deems both Jimmy Savile and Phil Spector good blokes) into a rougher sort of genre altogether, rather in the way that the “retainer” recklessly drives his boss’s low-slung Ferrari Dino down rutted rural lanes. He never quite does that, although the comedy sometimes teeters on the brink – as when “Sir Crofton the Creepy” (as Nat shrewdly dubs him) showers himself while employing a pair of Auralie’s blue French knickers as a flannel and involuntarily suffers “an inevitable act of gender-based biology”. Well, that’s one way of putting it.

Creepy Crofton’s voice trademarks Kitchenly 434 (the manor’s phone number) more decisively than Marko’s blazing solos put their stamp on a Fear Taker gig. For the most part, it’s a triumph and a treat – unctuous, pretentious, borderline sinister, yet skin-crawlingly fragile. (During a disastrous, even if age-appropriate, pub date with Abigail, he recalls that “I always felt people were about to reprimand me or laugh in my face if they looked me in the eye”). Indeed, Crofton often sounds like kin not just to Ishiguro’s self-abasing butler Stevens but Alan Partridge or David Brent. This strain of TV sitcom, or Mike Leigh-style wincing anguish, can serve Warner well. However, he lets it run out of control, like a guitar-and-synth marathon on a Genesis-era concept album. Scenes of the crazy villagers tend to outstay their welcome, although Warner has some delectable fun with his rustic grotesques, from the mad fag-puffing GP and the demon barber who turns Crofton punk to Dan Mullan himself – that “wizard with a dung load” who likes to chuck dead badgers into the manor’s septic tank because “nothing breeds up the maggots good like a fresh bit of wildlife”.

Creepy Crofton’s voice trademarks Kitchenly 434 (the manor’s phone number) more decisively than Marko’s blazing solos put their stamp on a Fear Taker gig. For the most part, it’s a triumph and a treat – unctuous, pretentious, borderline sinister, yet skin-crawlingly fragile. (During a disastrous, even if age-appropriate, pub date with Abigail, he recalls that “I always felt people were about to reprimand me or laugh in my face if they looked me in the eye”). Indeed, Crofton often sounds like kin not just to Ishiguro’s self-abasing butler Stevens but Alan Partridge or David Brent. This strain of TV sitcom, or Mike Leigh-style wincing anguish, can serve Warner well. However, he lets it run out of control, like a guitar-and-synth marathon on a Genesis-era concept album. Scenes of the crazy villagers tend to outstay their welcome, although Warner has some delectable fun with his rustic grotesques, from the mad fag-puffing GP and the demon barber who turns Crofton punk to Dan Mullan himself – that “wizard with a dung load” who likes to chuck dead badgers into the manor’s septic tank because “nothing breeds up the maggots good like a fresh bit of wildlife”.

Crofton’s plangent tones, though, must also carry Warner’s own sensibility: his bittersweet passages of pastoral prose; his insight into “the mysterious energies of world fame” that drive Marko; his shrewd picture of the way that newly-rich rock stars from deferential homes slotted into the ancient hierarchies of rural life as if (almost) to the manor born. And, through hapless Crofton, we get to share Warner’s scrutiny of the hidden fault-lines – historical and economic – that will soon make this dream decay. “Security and the preservation of boundaries,” preoccupy Crofton – especially that riskily unfenced stretch of ground on one side of the house, open to nocturnal intruders. “Borders. They are vitally important.” Kitchenly 434 smartly leaves the gate into a crueller world beyond its comic idyll fractionally open. “At the end of the day,” Marko will declare when he speaks at last, “it’s all about ego and money.” Through Crofton’s summer of ’79, however, the sun shines bright over manor, moat and mill race. And there are Gypsy Creams still for tea.

- Kitchenly 434 by Alan Warner (White Rabbit, £18.99)

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Add comment