Like an angry teenager rejecting everything his parents stand for, American artist Mike Kelley embraced everything most despised by the art world – from popular culture to crafts, and occultism to catholicism – to create what he ironically called “blue collar minimalism”. “An adolescent,” he declared, “is a dysfunctional adult and art is a dysfunctional reality”.

Noisy, anarchic, silly and disturbing, Kelley’s unruly output makes for uneasy viewing. Despite Tate Modern’s attempts to civilise and rationalise his work, the galleries are filled with the raucous din of loud music and singing plus shouting, yelling and full volume screaming which makes one desperate to escape his dystopian world view.

Born into a working-class, Catholic family in Detroit, he clearly felt like an outsider at California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) where he studied from 1976-8. Turning his sense of alienation into a strength, he embraced what he called the “negative joy” of refusing to conform to art world trends. Since minimalism (the current orthodoxy) espoused all things neat, tidy and rational – the clarity, logic and anonymity of pure geometry – Kelley opted for the messiness and anarchy of meaningless lectures, childish performances and daft videos.

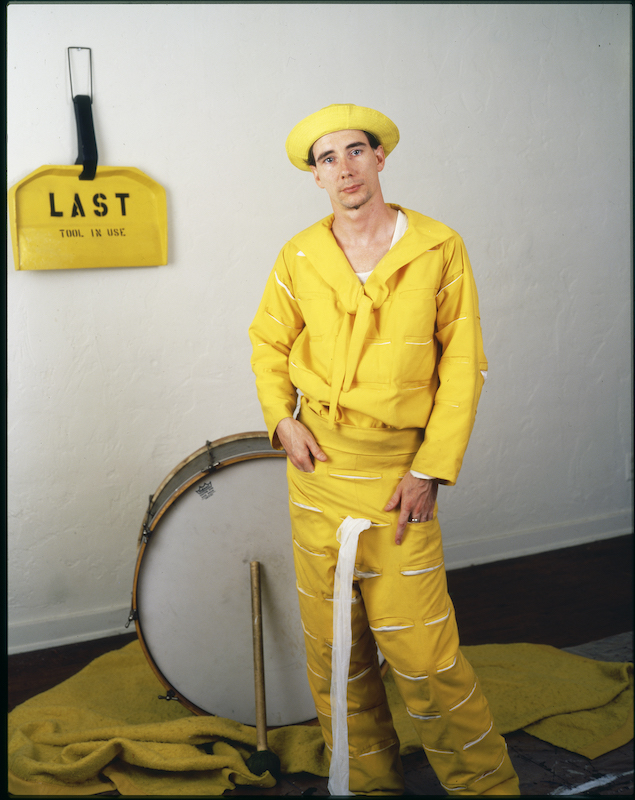

He photographed himself as a medium with ectoplasm streaming from his nostrils, gave lectures “with all the sense taken out” and filmed himself as the Banana Man (pictured right), a character from a children’s television series that he’d never seen. Despite playing a fool who continually makes “bad decisions”, Kelley’s Banana Man also gazes into “the pond, the stagnant soup of life” and poses serious questions such as “Is there growth without movement?” And the video ends with him lying on the floor adopting the shape of a “big yellow question mark”.

He photographed himself as a medium with ectoplasm streaming from his nostrils, gave lectures “with all the sense taken out” and filmed himself as the Banana Man (pictured right), a character from a children’s television series that he’d never seen. Despite playing a fool who continually makes “bad decisions”, Kelley’s Banana Man also gazes into “the pond, the stagnant soup of life” and poses serious questions such as “Is there growth without movement?” And the video ends with him lying on the floor adopting the shape of a “big yellow question mark”.

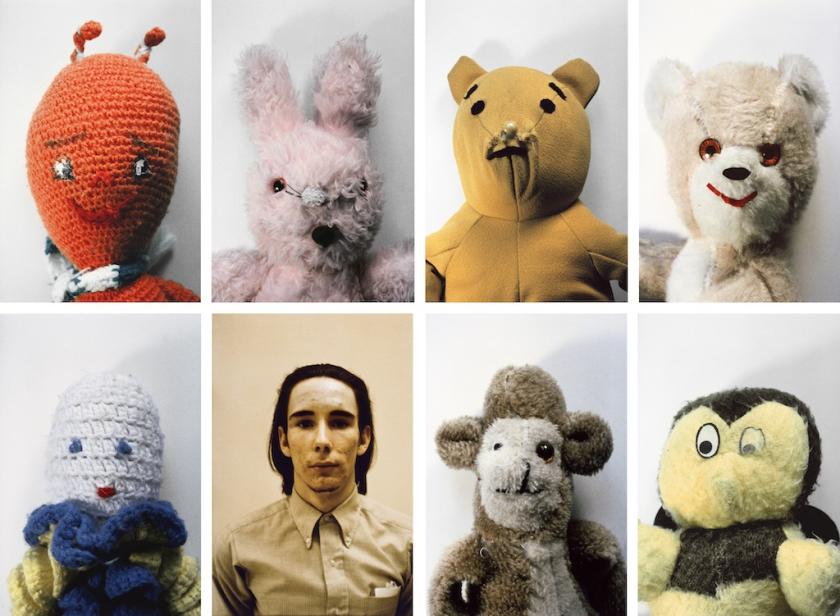

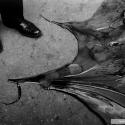

If minimalism enshrined the idea that art exists on a higher plane than sordid reality, Kelly chose to dive into the dirt – literally – by making drawings of comic strip renderings of rubbish. He also lifted the lid on the parent/child relationship with installations of home-made stuffed toys bought in thrift shops. More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid (pictured below) is made from stuffed toys crammed together into a claustrophobic blanket that threatens to engulf you with the neediness of love. Because it can’t ever be fully repaid parental love, it suggests, can feel suffocating.

In Ahh… Youth 1991 (main picture), the artist’s pock-marked face is juxtaposed with portraits of cuddly toys whose battered faces are evidence of harsh treatment. If his acne is indicative of the emotional turmoil experienced in adolescence, their disfigured features suggest that childhood is similarly taxing.

When his grimy, soft toy pieces were shown in Los Angeles in 1987, critics assumed they were indicative of childhood abuse. Kelley decided to capitalise on the suggestion and began exploring repressed memory syndrome, an idea fashionable at the time which posits that you may be unaware of childhood trauma because you are suppressing the memory.

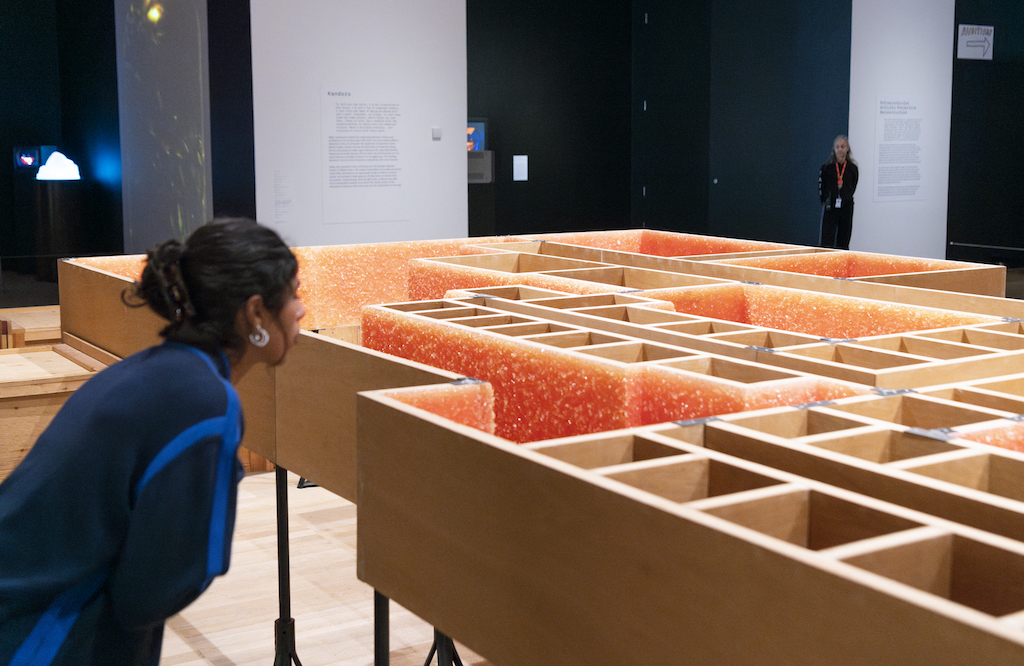

Educational Complex, 1995 is a set of architectural models of the institutions that shaped his behaviour and beliefs including his family home, church and high school. Then comes Sublevel, 1998 (pictured below) a large plywood model of the basement of CalArts with sections of the building he didn’t remember coated in crystals of pink resin, as if to suggest that “my secret indoctrination in perversity” could have happened there.

Educational Complex, 1995 is a set of architectural models of the institutions that shaped his behaviour and beliefs including his family home, church and high school. Then comes Sublevel, 1998 (pictured below) a large plywood model of the basement of CalArts with sections of the building he didn’t remember coated in crystals of pink resin, as if to suggest that “my secret indoctrination in perversity” could have happened there.

It’s not until you get to Extra Curricular Activity Projective Reconstructions, 2000-2011 that you realise just how bizarre was Kelley’s upbringing. Photographs from his high school yearbooks show children involved in weird rituals and religious ceremonies. Kelley restages the photographs as carnivalesque performances – opportunities for rule breaking and general mayhem.

Each May, they crowned the statue of the Virgin Mary with flowers. Kelley transforms what was initially a pagan fertility ritual into a horror movie starring the Virgin as evil marauder rampaging after young women. Another video shows students arguing the merits of stereotypical male celebrities. One girl claims Kobe Bryant as her ideal man (the basket ball player was charged with sexual assault), while another chooses R Kelly, the R&B singer charged with child sex abuse. The debate soon descends into a brawl “You slut; you’re like a sow in heat,” screams one girl as, egged on by classmates, she tears her opponent’s hair out. To a non-Catholic, non-American woman, Kelley’s restagings are as bewildering as the events that inspired them. They feel both insular and unhinged – as incomprehensible, in fact, as the prospect of a racist, misogynist, criminal narcissist being chosen as the next US president. Could Mike Kelley’s work provide an answer to this vexed question?

To a non-Catholic, non-American woman, Kelley’s restagings are as bewildering as the events that inspired them. They feel both insular and unhinged – as incomprehensible, in fact, as the prospect of a racist, misogynist, criminal narcissist being chosen as the next US president. Could Mike Kelley’s work provide an answer to this vexed question?

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment