After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art, National Gallery review - an impressive tour de force | reviews, news & interviews

After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art, National Gallery review - an impressive tour de force

After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art, National Gallery review - an impressive tour de force

But many names are missing from this international survey

What a feast! Congratulations are due to the National Gallery for its latest blockbuster After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art. Such a superb collection of modern masters is unlikely to be assembled again under one roof, so this is a once-in-a-lifetime, must-see exhibition.

Room after fabulous room is hung with a hundred artworks, mostly paintings, on walls painted navy blue. This daring decision works well for most artists, the exception being Van Gogh whose landscapes die against the dark background. Luckily the dark blue offsets the cream wallpaper and pale pink blouse of Van Gogh’s Woman from Arles 1880 (pictured right), who remains delightfully enigmatic.

Room after fabulous room is hung with a hundred artworks, mostly paintings, on walls painted navy blue. This daring decision works well for most artists, the exception being Van Gogh whose landscapes die against the dark background. Luckily the dark blue offsets the cream wallpaper and pale pink blouse of Van Gogh’s Woman from Arles 1880 (pictured right), who remains delightfully enigmatic.

The scene is set in the first room with Cézanne’s Large Bathers 1894–1905, the plaster cast for Rodin’s 1898 sculpture of Balzac wrapped in his dressing gown – a monumental figure that whooshes upwards like a force of nature – and a horribly fey, neo-classical idyll of half-naked nymphs by symbolist painter Pierre Puvis de Chavannes.

What follows is a ridiculously ambitious overview of the creative explosion that was unleashed after the Impressionists had broken free from the Academy and its constraints. The main focus of the show is on Paris where Cézanne, Degas, Gauguin and Van Gogh rightly take centre stage.

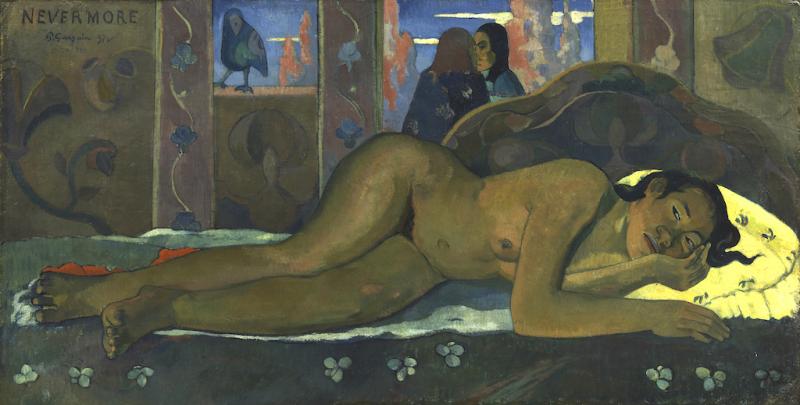

To avoid the exhibition becoming a check-list of the overly familiar, the curators needed to achieve the right balance between old favourites and less well known works. And they’ve got it just right. Degas’ famous, fiery red painting of a servant combing her mistress’s red hair, for instance, is juxtaposed with his lovely but little known pastel of a naked woman reading. And Gauguin’s much loved Nevermore 1897 (main picture), of his young Tahitian mistress lying on a bed, hangs near his painting of waves swirling round rocks, a much less familiar picture inspired by Japanese prints.

To avoid the exhibition becoming a check-list of the overly familiar, the curators needed to achieve the right balance between old favourites and less well known works. And they’ve got it just right. Degas’ famous, fiery red painting of a servant combing her mistress’s red hair, for instance, is juxtaposed with his lovely but little known pastel of a naked woman reading. And Gauguin’s much loved Nevermore 1897 (main picture), of his young Tahitian mistress lying on a bed, hangs near his painting of waves swirling round rocks, a much less familiar picture inspired by Japanese prints.

In the next room, far too much space is given to the pointillism of Seurat and Signac, which proved to be an artistic dead end, and not enough to members of the Nabis group, like Bonnard and Vuillard, whose influence was long lasting. A little gem to look out for is Vuillard’s 1891 portrait of the Symbolist poet Lugné-Poe hunched over a scrap of paper, scribbling.

One of the most important exhibits is among the least noticeable. In 1888 under the guidance of Gauguin, Paul Sérusier painted for his fellow Nabis a small landscape (pictured above left) that demonstrated the need to see a painting primarily as a flat surface covered in patches of paint. This little panel came to be known as The Talisman and the idea – of retaining the integrity of the picture plane – became a guiding principle for many painters right through to the abstract expressionists. It may not look like much, but its significance can’t be overstated, so seek it out and, later in the last room, you’ll also find Matisse and Derain following the advice.

Another delight is James Ensor’s 1889 painting of a masked woman viewing a heap of puppets and musical instruments abandoned in an otherwise empty room. This mysterious picture hangs in a side gallery dedicated to Barcelona and Brussels, whose main purpose seems to be to introduce a youthful Picasso trying out various styles.

Another delight is James Ensor’s 1889 painting of a masked woman viewing a heap of puppets and musical instruments abandoned in an otherwise empty room. This mysterious picture hangs in a side gallery dedicated to Barcelona and Brussels, whose main purpose seems to be to introduce a youthful Picasso trying out various styles.

Most interesting for me, because it shows divergent approaches to picture making, is the room devoted to developments in Vienna and Berlin. At one end of the room hangs Lovis Corinth’s Nana 1895 (pictured right). Inspired by the call girl heroine of Emile Zola’s novel, Corinth’s seated nude is so meaty and so full of vitality that she seems about to burst out of the frame. At the other end is Gustav Klimt’s 1904 portrait of the collector Hermine Hallia. Dressed in a diaphanous white gown and seen indistinctly as through a mist, Hallia is no more substantial than a wraith. While Klimt painted with feathery flicks of the brush, Corinth lathered on the paint in muscular strokes that seem almost to massage the woman’s substantial flesh into being.

Between these two extremes hangs Eduard Munch’s 1910 portrait of the Consul Christen Sandberg (pictured below full column). It’s an inspired juxtaposition, because Munch achieves the sculptural power of Corinth’s picture with the deft paint handling of Klimt. Using oils diluted to filmy liquidity, he conjures the huge physical presence of this portly gentleman. The magic sought by the Nabis – of an evidently flat surface that conjures an illusion of 3D – is effortlessly delivered in an image that is, at once, both flimsy and monumental.

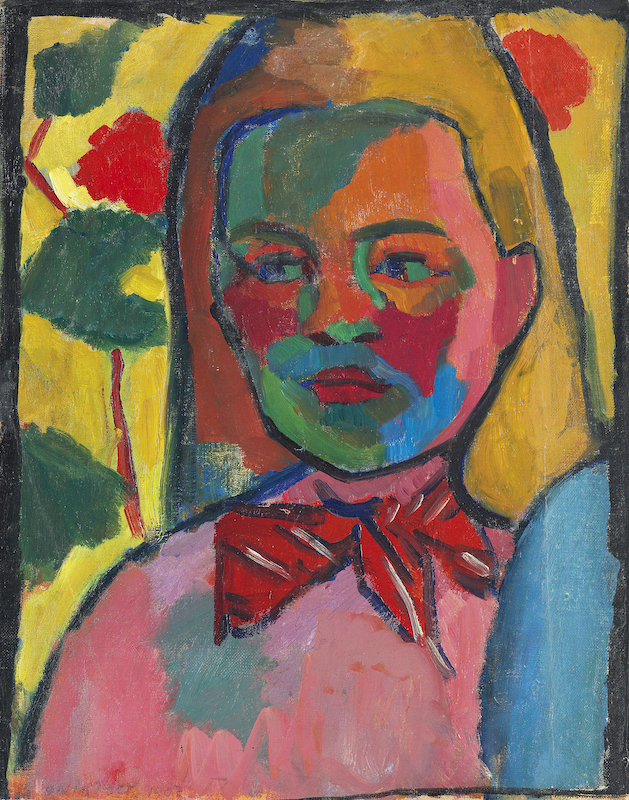

The cut off date for the exhibition is 1914 and the last room tries to encompass the remaining years, in too small a space. There are some wonderful things on show here, but I was distracted by the absence of so many significant groups and individuals. While Derain and Matisse of Les Fauves are included, their German expressionist counterparts (Die Brücke) get short shrift. Sonia Delaunay is represented by a gloriously colourful portrait (pictured left), but her husband Robert is absent. The Italian Futurists are missing along with Russian painters like Aleksandra Ekster and Liubov Popova who studied in Paris before going home to achieve great things. The Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider) are not included, nor is Fernand Léger’s idiosyncratic brand of cubism or Marcel Duchamp’s seminal painting Nude Descending a Staircase 1912.

The cut off date for the exhibition is 1914 and the last room tries to encompass the remaining years, in too small a space. There are some wonderful things on show here, but I was distracted by the absence of so many significant groups and individuals. While Derain and Matisse of Les Fauves are included, their German expressionist counterparts (Die Brücke) get short shrift. Sonia Delaunay is represented by a gloriously colourful portrait (pictured left), but her husband Robert is absent. The Italian Futurists are missing along with Russian painters like Aleksandra Ekster and Liubov Popova who studied in Paris before going home to achieve great things. The Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider) are not included, nor is Fernand Léger’s idiosyncratic brand of cubism or Marcel Duchamp’s seminal painting Nude Descending a Staircase 1912.

Piet Mondrian’s shift towards abstraction is deftly demonstrated in three paintings of trees, but Vassily Kandinsky, that other doyen of abstraction, is represented by a Murnau landscape that gives no hint of future developments when the inclusion of the Tate’s delicate Cossacks 1911, for example, would have amply demonstrated his transition away from figuration.

Gaps like these make a nonsense of the show’s claim to be “a wide ranging international survey”, yet with so many world famous pictures included, it seems churlish to complain. Better to concentrate on what’s actually present. Matisse’s 1906 portrait of his daughter reading is achieved entirely through colour, as proposed by the Nabis. An incredible variety of strokes – from dabs, blobs, squiggles and scrawls to vigorous brushmarks and areas of flat paint – are used to conjure a delightful interior.

Gaps like these make a nonsense of the show’s claim to be “a wide ranging international survey”, yet with so many world famous pictures included, it seems churlish to complain. Better to concentrate on what’s actually present. Matisse’s 1906 portrait of his daughter reading is achieved entirely through colour, as proposed by the Nabis. An incredible variety of strokes – from dabs, blobs, squiggles and scrawls to vigorous brushmarks and areas of flat paint – are used to conjure a delightful interior.

At the other extreme is the cubism of Picasso and Braque. In almost monochromatic paintings, they rely on tone to explore the interplay of objects and the space around them. Picasso’s monumental 1909 portrait of his lover Fernande (pictured above right) looks as if it has been carved out of wood; it's a shame that one of the bronze sculptures he made of her at the same time is not included.

Sculpture is given a secondary role in the show, but a wonderfully craggy bronze from 1901 of Beethoven’s head by Antoine Bourdelle is a reminder that sculptors also played a part in the sprint towards greater self expression to which this major exhibition bears witness with such aplomb.

Sculpture is given a secondary role in the show, but a wonderfully craggy bronze from 1901 of Beethoven’s head by Antoine Bourdelle is a reminder that sculptors also played a part in the sprint towards greater self expression to which this major exhibition bears witness with such aplomb.

- After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art is at the National Gallery until 13 August

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment