Uncle Vanya, Almeida Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

Uncle Vanya, Almeida Theatre

Uncle Vanya, Almeida Theatre

Robert Icke's lengthy revival/reappraisal is largely a knockout

Uncle Johnny instead of Vanya, a passing reference to sharia law, and nary a samovar in sight: surely this can't be the Uncle Vanya that has long been a cornerstone of the British theatre, especially in a new version from its take-no-prisoners director, Robert Icke, that presents the four-act text with three (!) intervals?

Well, you can relax. Only the most authoritarian of purists will fail to find Chekhov's eternally wounding masterwork in correspondingly full flower across just as lengthy an evening as Icke's career-making Oresteia last year – and even more emotionally replete, as befits this most durably sorrowful of texts. Some won't like having to stand and stretch three different times for a play I have seen performed straight through and will wonder what David Bowie and Iggy Pop are doing in a landscape more frequently associated with the plangent strains of the guitar-playing Telegin (or Waffles): a character here renamed Cartwright in keeping with an Anglicisation that refers to the eco-warrior doctor Astrov by his first name, Michael (the superb Tobias Menzies, pictured below). Icke's governing intention is to collapse the distance between a spectator in Islington in 2016 and anything that might feel remote or foreign about this cornerstone of the Russian repertoire, while all the while offering up the play with its abiding ache intact. Indeed, this Vanya is the first I've experienced since Katie Mitchell's landmark production for the Young Vic in 1998 to match the fabled reports of the soulfulness that is said to have attended the legendary Russian-language productions of this play. The Russian versions I have seen in London are too often either preserved in aspic or served up as an excuse for the kind of hammy thespian grandstanding that this magnificently acted version at almost every turn eschews.

Icke's governing intention is to collapse the distance between a spectator in Islington in 2016 and anything that might feel remote or foreign about this cornerstone of the Russian repertoire, while all the while offering up the play with its abiding ache intact. Indeed, this Vanya is the first I've experienced since Katie Mitchell's landmark production for the Young Vic in 1998 to match the fabled reports of the soulfulness that is said to have attended the legendary Russian-language productions of this play. The Russian versions I have seen in London are too often either preserved in aspic or served up as an excuse for the kind of hammy thespian grandstanding that this magnificently acted version at almost every turn eschews.

In performance terms, the undeniable occasion of the night is the return to the Chekhov fold of Paul Rhys, who pulled out of playing Ivanov at the National Theatre in 2002 but here more than compensates with a Vanya/Johnny that seems to originate from somewhere very deep and dangerous within. His gait either unsteady or heavy, as if moving through the maze-like provincial estate where the play is (on this occasion placelessly) set were itself a burden, Rhys cuts a shambolic figure steeped in self-loathing and shame for the title character's unreciprocated longings and lack of fulfillment: a would-be Schopenhauer or Nietzsche taken over by a consumptive awareness of his own inadequacies.

And when he lashes out in the third of the four acts, we might as well be watching a suppurating wound made flesh. I intend it as the most profound of compliments to say that this performance looks as if it hurts, and Rhys throughout remains at one with a governing darkness in the character that made me think this might well be the first Vanya who at some later date does actually kill himself, Sonya's celebrated final appeal to patience – and to the angels – notwithstanding.

If Rhys plays Johnny either close to or in tears as the lacerations mount, Menzies's Michael (aka Astrov) neatly suggests the opposite. From his brilliantly realised opening encounter with the ageing Nanny (Ann Queensberry, well into her eighties, is lovely in that part) onwards, a low-voiced Menzies speaks as if something essential within him has been dulled to feeling. Traumatised by memories of his own medical missteps, Michael comes to life only in his libidinous dalliance with the gout-ridden Professor's far-younger wife, Elena (Vanessa Kirby, quietly ravishing); elsewhere, it's as if this character has himself been permanently anaesthetised, his response to life's abrasions being to shut himself off to feeling in inverse proportion to Johnny's absence of a carapace with which to deflect life's setbacks.

The action unfolds within a (mostly) rotating Hildegard Bechtler set that changes direction in the final act and that functions as a visual metaphor for Chekhov's peerless gift for viewing his personages in the round. And when the characters break the fourth wall to speak to us directly – a technique Chekhov employs in this more than any other play – the actors vault out of the frame and down to the front of the stalls to address the house as one. That same space is also utilised for the farewell scene when Hilton McRae's bruisingly dyspeptic Professor (pictured above, with Kirby behind) – a onetime aesthete gone terminally sour – departs with Elena for what is surely forever, leaving Johnny to clamber back up and into the visual wreck of a home where he and his adoring niece, Sonya (Jessica Brown Findlay, fresh from Icke's Oresteia) return to their accounts.

The action unfolds within a (mostly) rotating Hildegard Bechtler set that changes direction in the final act and that functions as a visual metaphor for Chekhov's peerless gift for viewing his personages in the round. And when the characters break the fourth wall to speak to us directly – a technique Chekhov employs in this more than any other play – the actors vault out of the frame and down to the front of the stalls to address the house as one. That same space is also utilised for the farewell scene when Hilton McRae's bruisingly dyspeptic Professor (pictured above, with Kirby behind) – a onetime aesthete gone terminally sour – departs with Elena for what is surely forever, leaving Johnny to clamber back up and into the visual wreck of a home where he and his adoring niece, Sonya (Jessica Brown Findlay, fresh from Icke's Oresteia) return to their accounts.

At times, the sought-for rawness of Icke's rendingly felt view of the material recedes. There are moments of calculation that feel especially phony amidst the "real-ness" that prevails elsewhere: Cartwright's sudden outburst, for instance, early on, or Findlay's androgynous, deliberately desexed Sonya letting rip about her "volatile" environs – an outburst that is itself notably volatile.

Elsewhere, though, I appreciated the multiple intervals in much the same way that you pause between great paintings while visiting a gallery so as to absorb what you have seen, the difference here being that the canvas walks and talks and its characters live among us. "I'm ruined, wrecked, completely destroyed," Johnny remarks near the end, by which point he might as well be speaking for the audience.

MORE CHEKHOV ON THEARTSDESK

The Cherry Orchard, National Theatre (2011). Zoë Wanamaker (pictured below) shines in Howard Davies's murky production of Chekhov

The Cherry Orchard, Sovremennik, Noël Coward Theatre (2011). Russians soar in third, and final, offering of their first-ever London season

Uncle Vanya, The Print Room (2012). Iain Glen stars in a version of Chekhov at his most tenderly intimate

A Provincial Life, National Theatre Wales (2012). Moments of visual beauty punctuate a Chekhov adaptation that struggles to find its focus

Three Sisters, Young Vic (2012) Benedict Andrews' energetic update is stronger on ensemble work than individual performances

Uncle Vanya, Vakhtangov Theatre Company (2012). Anti-naturalistic Russian Chekhov buries humanity under burlesque and mannerism

Uncle Vanya, Vakhtangov Theatre Company (2012). Anti-naturalistic Russian Chekhov buries humanity under burlesque and mannerism

Uncle Vanya, Vaudeville Theatre. Anna Friel, Laura Carmichael and Ken Stott shine bright in Lindsay Posner's production of Chekhov's drama

Longing, Hampstead Theatre (2013). William Boyd's dramatisation of two Chekhov stories with Iain Glen and Tamsin Greig is more pleasant than towering

The Cherry Orchard, Young Vic (2014). Katie Mitchell delivers Chekhov's masterpiece with devastating power

Uncle Vanya/Three Sisters, Wyndham's Theatre (2014). Quiet truth in finely observed ensemble Chekhov from the Mossovet State Academic Theatre

Winter Sleep. Turkish master Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Cannes Palme d'Or winner, based on Chekhov short stories, is huge in every sense

The Seagull, Regent's Park Open Air Theatre (2015). Strikingly staged Chekhov continues a strong season in the park

Young Chekhov, National Theatre (2016). Jonathan Kent's three-play Chekhovathon builds to a shattering climax

Wild Honey, Hampstead Theatre (2016). Early Chekhov begins strongly then falls away

ROBERT ICKE: HIS CAREER SO FAR

ROBERT ICKE: HIS CAREER SO FAR

Boys. Ella Hickson’s new play is fuelled by testosterone but floats on nuance

Mr Burns. A startling vision of a post-apocalyptic world dominated by The Simpsons

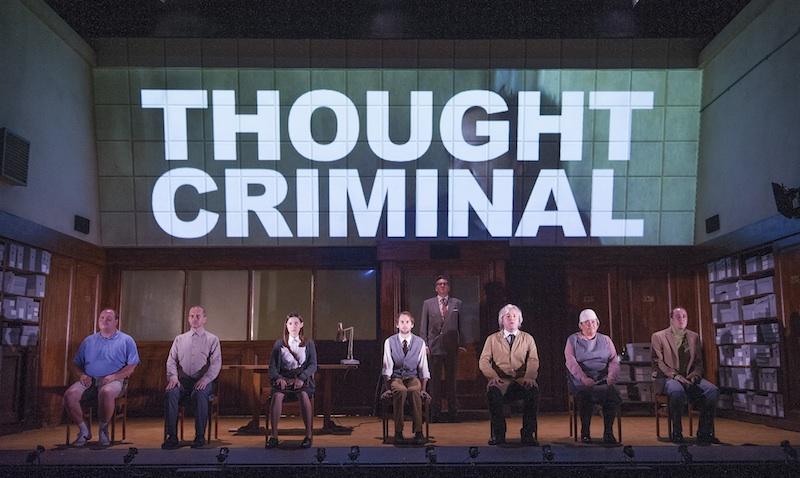

1984 (pictured by Tristram Kenton) Headlong's adaptation of George Orwell's novel is a theatrical coup

Oresteia. Lia Williams stands firm on the bones of Aeschylus in uncertain makeover

The Red Barn. David Hare’s latest is a superb adaptation of a Simenon thriller

Mary Stuart. Juliet Stevenson and Lia Williams electrify as four Schiller queens

Hamlet Predictably unpredictable performance from Andrew Scott subject to Icke's slow-burn clarity

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Red Speedo, Orange Tree Theatre review - two versions of American values slug it out

Timely arrival for Lucas Hnath's play about the cost of winning

Red Speedo, Orange Tree Theatre review - two versions of American values slug it out

Timely arrival for Lucas Hnath's play about the cost of winning

ECHO, LIFT 2024, Royal Court review - enriching journey into the mind of an exile

Nassim Soleimanpour's latest 'cold read' work is a unique experience

ECHO, LIFT 2024, Royal Court review - enriching journey into the mind of an exile

Nassim Soleimanpour's latest 'cold read' work is a unique experience

The Hot Wing King, National Theatre review - high kitchen-stove comedy, with sides of drama

Katori Hall is back in her native Memphis with an exuberant ensemble piece

The Hot Wing King, National Theatre review - high kitchen-stove comedy, with sides of drama

Katori Hall is back in her native Memphis with an exuberant ensemble piece

Hello, Dolly!, London Palladium review - Imelda Staunton makes every line a deal-broker

Operettaish bitter-sweetness raised to the sublime in a miracle of perfect timing

Hello, Dolly!, London Palladium review - Imelda Staunton makes every line a deal-broker

Operettaish bitter-sweetness raised to the sublime in a miracle of perfect timing

The Baker's Wife, Menier Chocolate Factory review - loving reappraisal doesn't entirely, well, rise

An imperfect show arrives boasting a quasi-immersive charm

The Baker's Wife, Menier Chocolate Factory review - loving reappraisal doesn't entirely, well, rise

An imperfect show arrives boasting a quasi-immersive charm

More Than One Story review - nine helpings of provocative political theatre

Cardboard Citizens shine an unforgiving light on poverty in the UK

More Than One Story review - nine helpings of provocative political theatre

Cardboard Citizens shine an unforgiving light on poverty in the UK

Visit from an Unknown Woman, Hampstead Theatre review - slim, overly earthbound slice of writer's angst

Christopher Hampton's love of Stefan Zweig's text becomes a drawback

Visit from an Unknown Woman, Hampstead Theatre review - slim, overly earthbound slice of writer's angst

Christopher Hampton's love of Stefan Zweig's text becomes a drawback

Grud, Hampstead Theatre review - sparky investigation of a geeky friendship

Two awkward science nerds and a violent alcoholic father are oddly likeable company

Grud, Hampstead Theatre review - sparky investigation of a geeky friendship

Two awkward science nerds and a violent alcoholic father are oddly likeable company

Skeleton Crew, Donmar Warehouse review - slow burn that satisfyingly catches fire

A fine cast spell out the cost of survival in today's ailing industries

Skeleton Crew, Donmar Warehouse review - slow burn that satisfyingly catches fire

A fine cast spell out the cost of survival in today's ailing industries

Next to Normal, Wyndham's Theatre review - rock musical on the trauma of mental illness

Award-winning production comes to West End - bring your handkerchiefs

Next to Normal, Wyndham's Theatre review - rock musical on the trauma of mental illness

Award-winning production comes to West End - bring your handkerchiefs

Mnemonic, Olivier Theatre review - thanks for the memories

Complicité’s reflection on memory, connection and storytelling remains as potent as ever

Mnemonic, Olivier Theatre review - thanks for the memories

Complicité’s reflection on memory, connection and storytelling remains as potent as ever

Starlight Express, Troubadour Wembley Park Theatre review - freight is kinda great

Andrew Lloyd Webber's 1980s spectacular skates into a new era

Starlight Express, Troubadour Wembley Park Theatre review - freight is kinda great

Andrew Lloyd Webber's 1980s spectacular skates into a new era

Add comment