If the distance from Festen to The Railway Children looks like a long stretch of track, remember that Mark-Anthony Turnage’s operas have often thundered through the drama of shattered families mired in mystery and secrecy – all the way back to the Oedipal conflicts of Greek in 1988.

Now, in the the same year as a Covent Garden triumph with his version of the dysfunctional dynasty of Thomas Vinterberg’s Danish film, the composer returns with a project he first conceived during the 2020 lockdown with librettist/partner Rachael Hewer. The pair have updated Edith Nesbit’s adored 1906 novel of official injustice, family fracture and youthful courage to the Cold War era of the early 1980s.

For the Glyndebourne autumn season, an ever-resourceful team – both musical and technical – pull every lever and grease every wheel to wave off a fast-moving show rich in spectacle, ingenuity, vocal commitment and (at decisive moments) credible emotion. Yet in crucial aspects, the update misfires: it complicates the original momentum and motivation of the plot without really enriching it. Smart and speedy, this Railway Children nonetheless rushes down a mistaken track. We seem to join the morally murky Le Carré-stye world of 1984, although ambience and attitudes tend to recall the 1960s instead – despite the kids’ wittily-written hunger for burgers and pizzas. Director Stephen Langridge says that he has never seen Lionel Jefferies’ film of 1970, with its seductive and enveloping Edwardian charm. Instead, we enter a bleaker, tenser landscape of geopolitical suspicion where the children’s parents – now activists Cathy and David – raid a government office in search of vital evidence of treachery. David is arrested (his rights strikingly sung to him); Cathy escapes. So, in a car evoked by one of the silhouettes created by Nicky Shaw’s design, she and their kids – Roberta, Peter, Phyllis – drive north through the night to begin their poverty-stricken exile in a chilly, but dainty, cottage (pictured above). Also on hand is Cathy’s friend Yolanda, a fellow-campaigner.

We seem to join the morally murky Le Carré-stye world of 1984, although ambience and attitudes tend to recall the 1960s instead – despite the kids’ wittily-written hunger for burgers and pizzas. Director Stephen Langridge says that he has never seen Lionel Jefferies’ film of 1970, with its seductive and enveloping Edwardian charm. Instead, we enter a bleaker, tenser landscape of geopolitical suspicion where the children’s parents – now activists Cathy and David – raid a government office in search of vital evidence of treachery. David is arrested (his rights strikingly sung to him); Cathy escapes. So, in a car evoked by one of the silhouettes created by Nicky Shaw’s design, she and their kids – Roberta, Peter, Phyllis – drive north through the night to begin their poverty-stricken exile in a chilly, but dainty, cottage (pictured above). Also on hand is Cathy’s friend Yolanda, a fellow-campaigner.

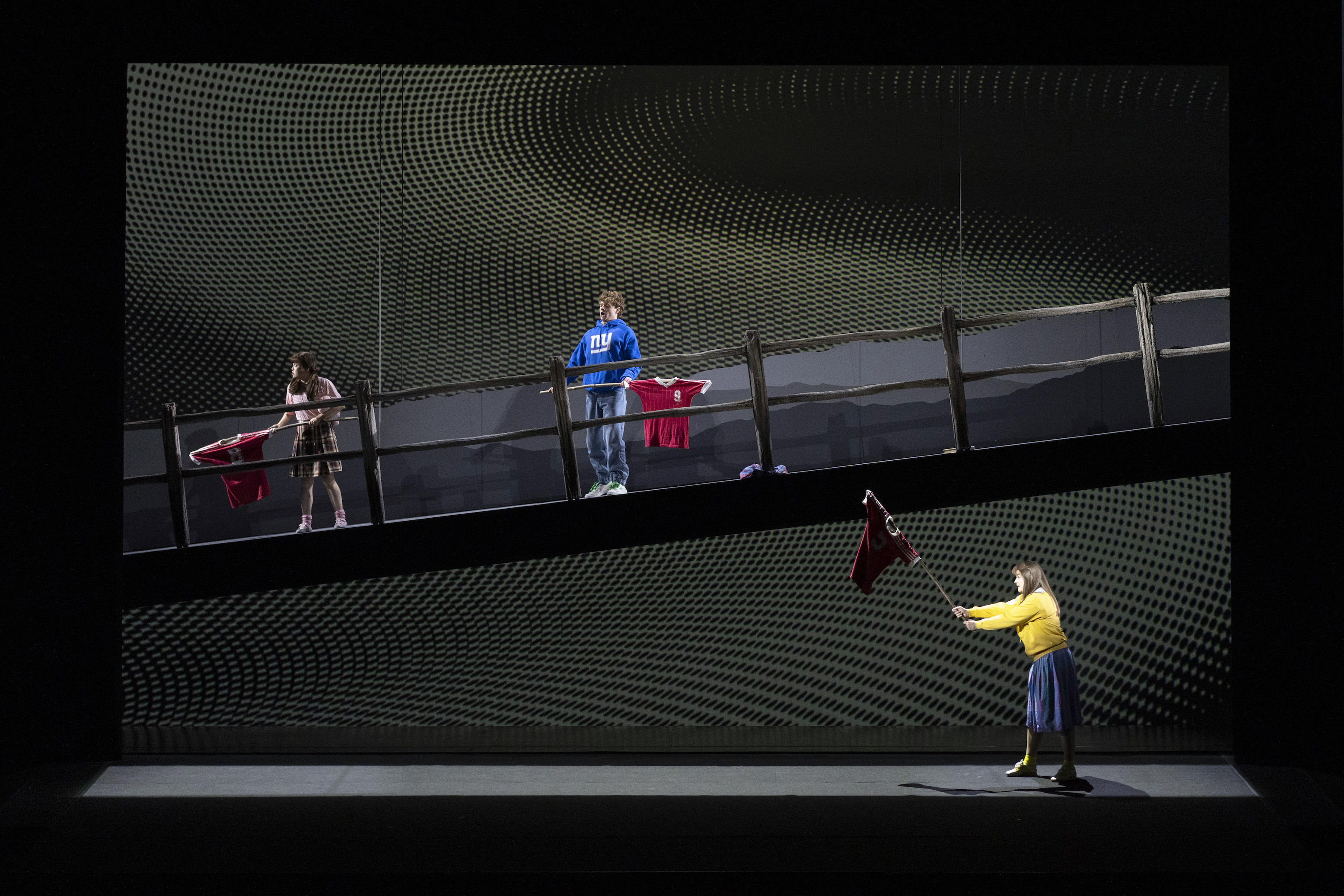

Many of Nesbit’s familiar signals remain in place. We meet the cheery stationmaster Mr Perks, devoted to the romance of rail (“This network to me is a work of art”); the distinguished gent on the train, now a retired, and revered, football legend named Sir Tommy Crawshaw, who intervenes to have Daddy’s case reviewed; the forlorn Russian exile, here Mr Tarpolski, whose arrival catalyses the action; the children’s flag-waving heroics to avert a disaster on the tracks (pictured below), and the final quashing of state injustice.  Langridge and Shaw, along with lighting and video designers Mark Jonathan and Max White, work hard and well to ensure that the staging delivers a full complement of gasp-worthy coups without ever overshadowing the characters and narrative. Scenes performed on different levels combine with backlit frames, square or rectangular, that expand and contract: they mimic not just the cinematic lens but the view from an observing agent’s camera. It’s an ingeniously sustained look that fits the presiding motif of surveillance, paranoia and espionage.

Langridge and Shaw, along with lighting and video designers Mark Jonathan and Max White, work hard and well to ensure that the staging delivers a full complement of gasp-worthy coups without ever overshadowing the characters and narrative. Scenes performed on different levels combine with backlit frames, square or rectangular, that expand and contract: they mimic not just the cinematic lens but the view from an observing agent’s camera. It’s an ingeniously sustained look that fits the presiding motif of surveillance, paranoia and espionage.

Silhouettes and video graphics summon, in a plausible but stylised way, the railway that comes to dominate the family’s spell of cold, fear and loneliness. They are supported by the train-like but never corny chugs, hoots and rattles of Turnage’s driving rhythms. Throughout, the orchestral and vocal writing feels lean, agile and eminently singable. Turnage never overdoses on those tempting train effects (though fans of, say, Honegger’s Pacific 231 will find enough to enjoy) and avoids too much period pastiche – even if the hapless Tarpolski’s lines in Russian trigger some brief Stravinskian allusions.

Not every musical excursion works: the (Britten-shaded?) satirical light relief as the local community pompously honours the reluctant kids after their life-saving mission feels forced and laborious. But hits outnumber misses. The eight-strong chorus of harassed but well-meaning commuters enjoy some rich polyphonic passages while the three children’s parts – particularly Roberta/Bobby – abound with flavour, mischief and, at key points, a heartfelt depth. Tim Anderson conducts the 16-strong Glyndebourne Sinfonia with a crisp alertness to the dabs of vibrant instrumental colour – celeste, harp, trombone, oboe – that Turnage spots around and between the vocal lines. Scenes of suspense, apprehension and discovery come with the spiky or shimmery effects of an Eighties spy-movie soundtrack (and did I detect a nod or two to the great Bernard Herrmann/Alfred Hitchcock scores?).

Turnage and Hewer are generously served by a cast that manage the tricky balance of feeling that this piece requires. Thoroughly accessible in music and action to young audiences, this work still feels in tone more like an adult than a children’s opera. The three youngsters, wrenched from home and comfort and plunged into doubt about the probity of their beloved father, express conflict and anxiety as well as charm: Jessica Cale (Bobbie), Matthew McKinney (Peter), and Henna Mun as the teddy-bear-clutching littl’un, Phyllis.  Bobbie’s lonely struggle to do the right thing after parental, and official, authority have crumbed elicits some of Turnage’s most tense but tender writing. Cale and McKinney (both Kathleen Ferrier Prize laureates) shone equally, with Mun their endearing, annoying sidekick. Rachael Lloyd, as Cathy (pictured above), made the most in poise and presence of the extra audacity that Hewer’s libretto has added to the Nesbit character. Doubling David and Tarpolski, Edward Hawkins’s bass had a haunted, yearning quality, a rasping edge of pain to match the anguish of both figures. As the joint substitute fathers in this archetypal tale of ideal parents mislaid and retrieved, Gavan Ring’s Perks (pictured below) and – in especially robust voice – James Cleverton’s benign deus ex machina Sir Tommy projected a winning warmth.

Bobbie’s lonely struggle to do the right thing after parental, and official, authority have crumbed elicits some of Turnage’s most tense but tender writing. Cale and McKinney (both Kathleen Ferrier Prize laureates) shone equally, with Mun their endearing, annoying sidekick. Rachael Lloyd, as Cathy (pictured above), made the most in poise and presence of the extra audacity that Hewer’s libretto has added to the Nesbit character. Doubling David and Tarpolski, Edward Hawkins’s bass had a haunted, yearning quality, a rasping edge of pain to match the anguish of both figures. As the joint substitute fathers in this archetypal tale of ideal parents mislaid and retrieved, Gavan Ring’s Perks (pictured below) and – in especially robust voice – James Cleverton’s benign deus ex machina Sir Tommy projected a winning warmth.

Yet, to this passenger at least, it still seems as if Hewer’s spy-themed diversion has taken a misconceived route. Nesbit’s unjustly accused Father was a noble Dreyfus figure, while the novel's Russian political refugee derived from the anarchist sage Prince Kropotkin and the exiled radical Sergei Stepniak, a darling of the Fabians. Here, the Cold War atmosphere undermines the adult idealism that, although challenged, gives the observing children a pattern for their pluck. The mixed motives, sham identities and intimate betrayals of the adults – Smiley’s people – generates a mood that detracts from the tests of courage that Bobbie (Jessica Cale, pictured below) must confront. Fair enough, if the musical and dramatic language allows for that inserted level of ambiguity to mature. Here, it does not.

Yet, to this passenger at least, it still seems as if Hewer’s spy-themed diversion has taken a misconceived route. Nesbit’s unjustly accused Father was a noble Dreyfus figure, while the novel's Russian political refugee derived from the anarchist sage Prince Kropotkin and the exiled radical Sergei Stepniak, a darling of the Fabians. Here, the Cold War atmosphere undermines the adult idealism that, although challenged, gives the observing children a pattern for their pluck. The mixed motives, sham identities and intimate betrayals of the adults – Smiley’s people – generates a mood that detracts from the tests of courage that Bobbie (Jessica Cale, pictured below) must confront. Fair enough, if the musical and dramatic language allows for that inserted level of ambiguity to mature. Here, it does not. The libretto teases us with hints of modern cynicism and duplicity, while the music and drama keep faith with the almost-mythological ordeals of the original story. This tension leads to a hasty and formulaic Big Reveal at the close. It carries little emotional weight and, if anything, dilutes the power of the final reunion with exonerated Daddy. Audiences, whatever their age, won’t regret their ride on Glyndebourne’s hi-tech, high-speed and expertly-steered train. Some might still hanker for a journey that ends at its traditional destination.

The libretto teases us with hints of modern cynicism and duplicity, while the music and drama keep faith with the almost-mythological ordeals of the original story. This tension leads to a hasty and formulaic Big Reveal at the close. It carries little emotional weight and, if anything, dilutes the power of the final reunion with exonerated Daddy. Audiences, whatever their age, won’t regret their ride on Glyndebourne’s hi-tech, high-speed and expertly-steered train. Some might still hanker for a journey that ends at its traditional destination.

- The Railway Children is performed at Glyndebourne twice on 1 November, and at Queen Elizabeth Hall on 8 November

- More opera reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment