Claire Tomalin: The Young H G Wells review – days of the comet | reviews, news & interviews

Claire Tomalin: The Young H.G. Wells review – days of the comet

Claire Tomalin: The Young H.G. Wells review – days of the comet

How did a poor, weedy kid from Bromley conquer the world's imagination?

In late 1894 an unknown 28-year-old science tutor and wannabe writer finished a story in his dismal lodgings just north of Euston station. Divorced, after a brief, calamitous marriage to a cousin, he lived with a new lover even though the hostile landlady cursed them loudly to her neighbours. Meanwhile, bankruptcy loomed and rattling trains billowed filthy smoke through their rooms.

But this supreme artificer of far-fetched yarns was about to star in one himself. In the frozen new year of 1895, a magazine began to serialise an outlandishly original tale that wedded ideas drawn from cutting-edge science to a mesmeric narrative power. It was called The Time Machine. Within weeks, publishing deals arrived and a reviewer hailed the newcomer as “a man of genius”.

At the same time, a short stint as a theatre critic led the young hopeful to meet – at the disastrous premiere of Henry James’s play Guy Domville – a voluble Irishman who refused to wear a dress suit and talked to him “like an elder brother”. That conversation went on for half a century, while the two friends – HG Wells and Bernard Shaw – freed the minds and expanded the horizons of readers all around the world.

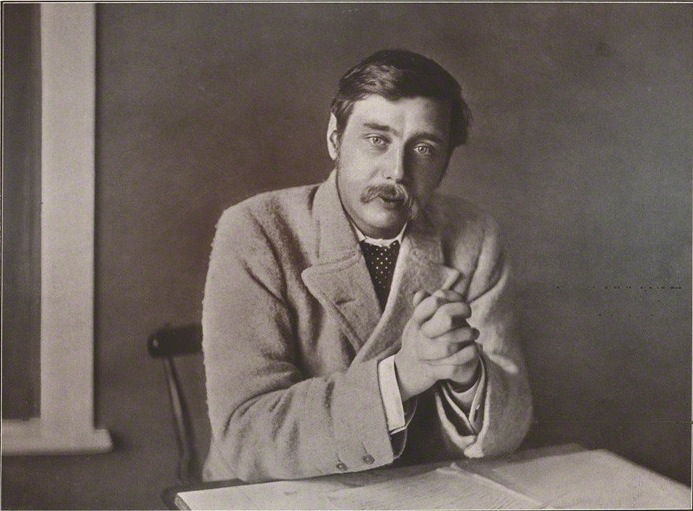

HG Wells [pictured above © National Portrait Gallery] hardly lacks for full-dress, cradle-to-grave biographers. Claire Tomalin, already the author of first-rate lives of figures including Samuel Pepys, Jane Austen, Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy, does not set out to supplant them. The Young H.G. Wells: Changing the World – which actually takes Wells up to his late forties, on the eve of the First World War – offers a different perspective. Tomalin delivers a succinct biographical and critical essay, full of her own inflections and emphases: a personal portrait, not a weighty chronicle. She connects Wells’s world-conquering imagination to the hardships and conflicts of his early life, and makes a persuasive case for the lasting value not just of his ideas but of his art.

HG Wells [pictured above © National Portrait Gallery] hardly lacks for full-dress, cradle-to-grave biographers. Claire Tomalin, already the author of first-rate lives of figures including Samuel Pepys, Jane Austen, Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy, does not set out to supplant them. The Young H.G. Wells: Changing the World – which actually takes Wells up to his late forties, on the eve of the First World War – offers a different perspective. Tomalin delivers a succinct biographical and critical essay, full of her own inflections and emphases: a personal portrait, not a weighty chronicle. She connects Wells’s world-conquering imagination to the hardships and conflicts of his early life, and makes a persuasive case for the lasting value not just of his ideas but of his art.

Of course, from Dr Who to Star Wars, entire modern constellations of science fiction owe a deep debt to Wells. Tomalin reminds us how boldly he could think and imagine; how powerfully he could write, in social comedies and topical polemics as well as speculative fantasies; and how he blew through cobweb-encrusted late-Victorian and Edwardian Britain like a liberating hurricane. With high spirits and good humour, too: typically, he told a friend that the futuristic prophecy of his 1901 book Anticipations “was designed to undermine and destroy the monarch, monogamy and respectability – and the British Empire, all under the guise of a speculation about motor cars and electric heating”.

This staggering confidence of a self-made celebrity whom Shaw, in his 1946 obituary, called “entirely classless”, accompanied a deep-seated “sense of entitlement” in professional and sexual relationships. Where did it originate? Wells, after all, grew up in Bromley, the weedy, infirm child of a domestic servant and a former gardener, and Kent county cricketer, who ran a failing shop. Tomalin finds a broad strain of eccentric self-belief in the family even though Bertie’s mother, Sarah, devoted much of her life to serving a grand family as housekeeper at Uppark in West Sussex.

Uppark’s mistress, however, was the sister of a dairymaid who, aged 20, had married a 71-year-old grandee. So a back-story of cross-class transgression helped make the mansion with its well-stocked library not just a second home for young Bertie but the welcoming place where he repeatedly convalesced after serious lung and kidney disease had almost killed him. For Tomalin, Uppark not only educated him; “his life was effectively saved there”. In the future, no door – social, intellectual, romantic – felt closed to him.

Although Sarah vainly tried to apprentice him in draper’s shops – which he detested – the new frontiers of science enraptured Wells, and led to a scholarship for trainee teachers at the future Imperial College in South Kensington. Sidetracked by writing and editing for student magazines, he flunked exams and scraped a living as a tutor while the early calamity of his marriage to cousin Isabel played out. Tomalin makes you grasp the torrential energy of this small, sickly kid from the precarious edge of the servant and shopkeeping class – and the attraction to women of his plucky, fizzing charm, which other, male biographers have enviously treated as something of a mystery. It certainly wasn’t just because his skin “smelled of honey”, as a later lover confided.

Although Sarah vainly tried to apprentice him in draper’s shops – which he detested – the new frontiers of science enraptured Wells, and led to a scholarship for trainee teachers at the future Imperial College in South Kensington. Sidetracked by writing and editing for student magazines, he flunked exams and scraped a living as a tutor while the early calamity of his marriage to cousin Isabel played out. Tomalin makes you grasp the torrential energy of this small, sickly kid from the precarious edge of the servant and shopkeeping class – and the attraction to women of his plucky, fizzing charm, which other, male biographers have enviously treated as something of a mystery. It certainly wasn’t just because his skin “smelled of honey”, as a later lover confided.

As a turn-of-the-century male progressive, Wells predictably believed in sexual “cakeism” in the Boris Johnson sense. The maverick genius should have unlimited rights of seduction and conquest, but must return home to a clean house, a laden table and a loyal spouse. With shrewdness and sympathy, Tomalin shows why mistresses and above all his second wife, Jane, connived at his double standard; Jane, who supported Wells’s girlfriends when the need arose, periodically emerges as “the true heroine of this story”.

Wells tended to form his extramarital liaisons not with compliant doormats but gifted, courageous, feminist free spirits: a guarantee of maximum turbulence on both sides. They included the writers Amber Reeves – Tomalin uses previously unpublished letters to her, full of fire and zest but also a hectoring neediness – and later Rebecca West, who (like Reeves) bore him a child.

Soon after The Time Machine, every door swung wide open to Wells. He channelled all the hopes and fears of an age of galloping scientific advance and deepening social conflict into one acclaimed visionary fable after another. Tomalin says relatively little about the familiar string of speculative classics that rapidly made Wells a global luminary: The War of the Worlds, The Island of Dr Moreau, The First Men in the Moon and so on. For that reason, her book doesn’t really serve as an introduction to the huge spinning galaxy of his imagination. Instead, she pivots to a celebration of lesser-known works that showcase his singular talents: such as the sparkling 1905 political parable This Misery of Boots (I wonder whether Terry Pratchett knew, and drew on, it in his much-quoted “Boots Theory” of social injustice in the Discworld series?), and the brilliantly observed, still under-rated, condition-of-England satire Tono-Bungay (1909).

Socialist, atheist, republican, Wells proudly advertised himself an an “extensive skeptic: no God, no King, no nationality”. Utopian fantasies such as In the Days of the Comet (1906) got him branded as a family-wrecking advocate of "free love" too: hypocritically, he denied that he preached what he privately practised. He plunged into the reformist politics of the Fabian Society – Tomalin outlines its history with a detail that could perhaps have have been devoted to other of his works – and characteristically tried to remake it in his own image.

Magnetically, he attracted friends in every high and influential place, from his Fabian sparring-partner Beatrice Webb to Winston Churchill, who ranked Wells alongside Swift, and almost every major writer of the era: Joseph Conrad, George Gissing, Henry James, as well as the devoted Shaw. Although it falls just outside her remit, Tomalin might have said more about Wells’s bitter rift with James in 1915 over the aims of literature: essentially, a battle between social purpose (Wells) and artistic autonomy (James) that rages to this day. Wells’s wilful cruelty to the ailing James bears out the friend who admitted that he could be both “the best company in the world”, but also “mean, spiteful and quarrelsome”.

Magnetically, he attracted friends in every high and influential place, from his Fabian sparring-partner Beatrice Webb to Winston Churchill, who ranked Wells alongside Swift, and almost every major writer of the era: Joseph Conrad, George Gissing, Henry James, as well as the devoted Shaw. Although it falls just outside her remit, Tomalin might have said more about Wells’s bitter rift with James in 1915 over the aims of literature: essentially, a battle between social purpose (Wells) and artistic autonomy (James) that rages to this day. Wells’s wilful cruelty to the ailing James bears out the friend who admitted that he could be both “the best company in the world”, but also “mean, spiteful and quarrelsome”.

Wells’s sheer charisma must have been extraordinary. As was his energy: 13 books between 1903 and 1910 alone, with lavish side-orders of journalism and lectures. By 1908, Tono-Bungay could command an advance of £1500: roughly £200,000 today. His reach was vast and his impact profound. Millions heard, and heeded, the call to envisage and create a better world summarised in This Misery of Boots: “Don’t submit… Don’t say for a moment ‘Such is life’.” His disciple William Beveridge, intellectual architect of the post-1945 Welfare State, called him “a volcano in perpetual eruption of burning thoughts and luminous images”. With a flair for colour, pace and plot that matches her subject’s, Tomalin does not bury him under a monumental tombstone. Instead, her dynamic sketch invites readers to discover – or rediscover – why that volcano still spits fire to light up a changing world.

- The Young H.G. Wells: Changing the World by Claire Tomalin (Viking, £20)

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Jessica Duchen: Myra Hess - National Treasure review - well-told life of a pioneering musician

Biography of the groundbreaking British pianist who was a hero of the Blitz

Jessica Duchen: Myra Hess - National Treasure review - well-told life of a pioneering musician

Biography of the groundbreaking British pianist who was a hero of the Blitz

Add comment