theartsdesk Q&A: Biographer Claire Tomalin on Charles Dickens | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Biographer Claire Tomalin on Charles Dickens

theartsdesk Q&A: Biographer Claire Tomalin on Charles Dickens

As the film of The Invisible Woman opens, its author - and Dickens's biographer - reflects on a very Victorian love affair

The tally of Charles Dickens’s biographers grows ever closer to 100. The English language’s most celebrated novelist repays repeated study, of course, because both his life and his work are so remarkably copious: the novels, the journals, the letters, the readings; the charitable works, the endless walks; the awful childhood, the army of children, the abruptly terminated marriage, the puzzling relationship with two sisters-in-law, the long and clandestine affair.

Vanishingly few of those biographers have been women. One of the many virtues of Claire Tomalin’s compact life of Dickens – it just scoots past 400 pages – is the invigorating perspective she brings to a field dominated by the male line. As she carefully illustrates, Dickens preferred the company of men - none more than his first biographer John Forster, to whom he confided the appalling story of the year he spent as a child in the infamous blacking factory. But domestically he surrounded himself with women. There were always three in his marriage to Catherine Hogarth: first her sister Mary, who died aged 17 in Dickens’s arms, whereafter he plunged into a period of ecstatic grief; then Georgina, who became his amanuensis and housekeeper and, during and after the divorce, sided not with her blood relative but the man who was, in effect, her creator.

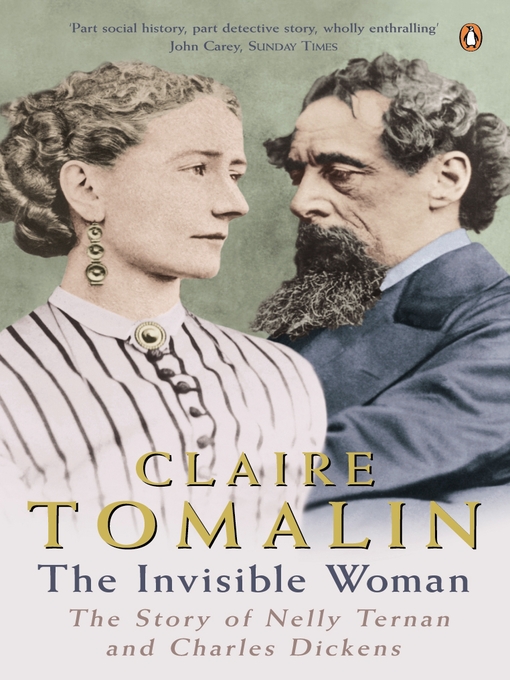

And then there was Nelly Ternan. Not long after Dickens built a partition through the marital bedroom, the young actress became Dickens’s mistress. It is not known when (or even, less plausibly, if) consummation occurred. Tomalin first told Nelly's story in The Invisible Woman (1990), which has now been made into a film directed by and starring Ralph Fiennes with Felicity Jones as Nelly (pictured). In the biography she adds more depth and detail to her portrait of a relationship which had such devastating repercussions. She more or less establishes that Nelly lost Dickens's baby while domiciled in France, and convincingly suggests that, hours before he died, the ailing Dickens may well have been delivered back by Nelly to Gad’s Hill, his home in Kent, so that his passing would not be tainted by scandal. The master's defenders have always found it hard to square the two Dickenses: the saviour who cared selflessly for the plight of fallen women, going so far as to found a home for them in Shepherds Bush; and the husband who ended his marriage so brutally.

And then there was Nelly Ternan. Not long after Dickens built a partition through the marital bedroom, the young actress became Dickens’s mistress. It is not known when (or even, less plausibly, if) consummation occurred. Tomalin first told Nelly's story in The Invisible Woman (1990), which has now been made into a film directed by and starring Ralph Fiennes with Felicity Jones as Nelly (pictured). In the biography she adds more depth and detail to her portrait of a relationship which had such devastating repercussions. She more or less establishes that Nelly lost Dickens's baby while domiciled in France, and convincingly suggests that, hours before he died, the ailing Dickens may well have been delivered back by Nelly to Gad’s Hill, his home in Kent, so that his passing would not be tainted by scandal. The master's defenders have always found it hard to square the two Dickenses: the saviour who cared selflessly for the plight of fallen women, going so far as to found a home for them in Shepherds Bush; and the husband who ended his marriage so brutally.

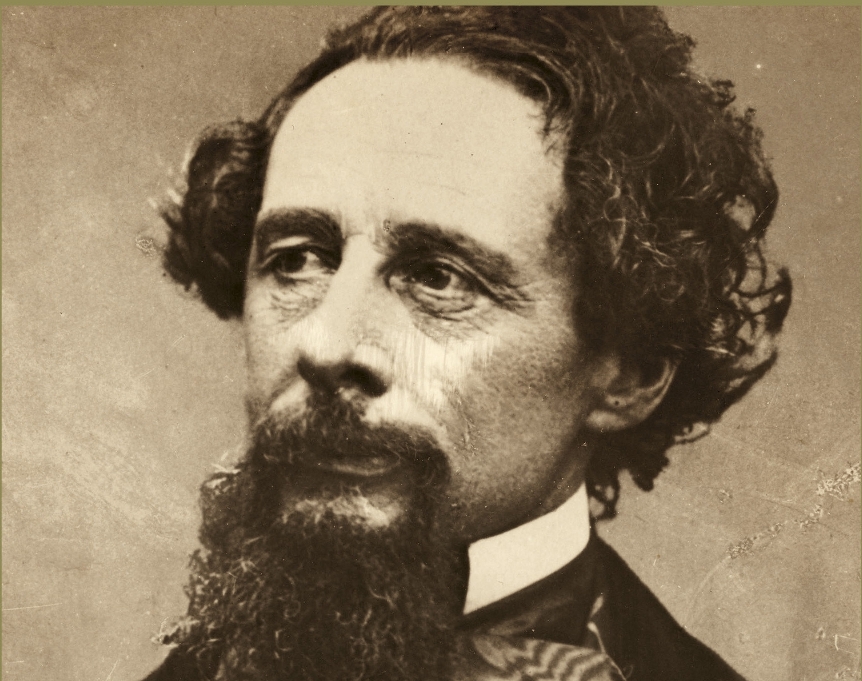

Claire Tomalin (b 1933) has also written acclaimed lives of Mary Wollstonecraft, Jane Austen, Samuel Pepys, Thomas Hardy and Katherine Mansfield. Having completed the greatest life of them all, she begins by telling theartsdesk how she found the previously unpublished image of Dickens used on the cover of her book Charles Dickens: A Life.

CLAIRE TOMALIN: I love this picture on the jacket and I found it in the files of the wonderful Dickens House Museum, which is full of treasures. I’ve never seen it reproduced and my friend Jenny Hartley, who is a good Dickens scholar, tells me she’s never seen it reproduced either. It shows his marvellous eyes. He had these beautiful eyes – somebody said “listening eyes”: he would listen to people with his eyes. You can see it must be about 1850 because he’s already got the moustache and the beard. He’s also wearing one of his dandy waistcoats - it looks like a tartan waistcoast. He dressed like a Regency man, always terribly smartly. I don’t think you can see any of his jewellery – he loved wearing jewellery, too: a lot of gold.

CLAIRE TOMALIN: I love this picture on the jacket and I found it in the files of the wonderful Dickens House Museum, which is full of treasures. I’ve never seen it reproduced and my friend Jenny Hartley, who is a good Dickens scholar, tells me she’s never seen it reproduced either. It shows his marvellous eyes. He had these beautiful eyes – somebody said “listening eyes”: he would listen to people with his eyes. You can see it must be about 1850 because he’s already got the moustache and the beard. He’s also wearing one of his dandy waistcoats - it looks like a tartan waistcoast. He dressed like a Regency man, always terribly smartly. I don’t think you can see any of his jewellery – he loved wearing jewellery, too: a lot of gold.

JASPER REES: He’s starting to look tired.

Yes, he is. Not surprisingly.

I want to ask the most obvious question of all to start with. How did this happen? How did you and Dickens hook up, given that 20 years ago you’d written The Invisible Woman?

Well, I hooked up with Dickens when I was about seven years old. I read David Copperfield first and I was completely bowled over by him. And I went on reading Bleak House – I can’t remember the order in which I read them. I didn't read them all until I was grown up. But I had the secret link that I had the same initials. I was called Claire Delavenay – CD. So when you’re a child and you keep writing your initials I kept thinking it was Charles Dickens’s initials too.

I didn’t want this to be a book that you’d have to take the breadknife to and saw in half before you read it

At Cambridge I studied him and I read Edmund Wilson’s essay “The Two Scrooges” and Edgar Johnson’s big 1950s biography of him and they both talked about Nelly Ternan, and rather slightingly, and didn't really say anything about her except that she’d been a rather bad mistake for Dickens. And I thought then – 13 years, 12 and a half years of his life he knew this young woman? There is a story there. And then in the 1980s I was working at The Sunday Times, it was in the Grays Inn Road just near Doughty Street and the Dickens House Museum and I went over to ask the curator something and I said, “I sometimes think about writing about Nelly Ternan.” He said, “I can’t tell you how many people I’ve told not to do that.” And then he stopped and looked at me and said, “But I think you might be the person to do it.”

Why do you think he thought that?

I’d published one book on Mary Wollstonecraft. I don’t know why he did. He was a most enchanting man. He’d got to look rather like Dickens the way curators do. So he gave me every assistance. And I was always very friendly with Graham Storey who taught my first husband at Cambridge, who was on the editors of the Pilgrim Letters [the Complete Letters of Dickens]. They were not published then and he let me see everything that I wanted to see. I was very fortunate with that book: it did very well and has gone on interesting people. But then of course I’ve always loved Dickens, I’ve gone on re-reading him and I thought, well, he only has a walk-on part in that book; perhaps it would be interesting to look at the whole picture.

Did you have your eye on the bicentenary or was that happenstance?

You may not believe me - I didn’t think of it but my publishers, who are a good deal more clued up than I am, displayed an extraordinary enthusiasm for the idea.

But once there is a bicentenary or any other form of anniversary you suddenly have a deadline looming into view which you can’t negotiate with.

It was five years. I said, “I can’t write this book in three years.” So it was all right. The other thing that happens is of course you have other books coming. But you just have to live with that. Practically every time I’ve written a biography I’ve found that someone else is covering the same ground in some way, or similar ground.

Can I ask you about the competition from the past? There are a lot of Dickens biographies including, most imposingly, the much larger life by Peter Ackroyd.

That came out 20 years ago at the same time as my Invisible Woman. I don't think 20 years is any reason that you can’t. Just as you can always paint a new portrait of an interesting face, you can always write a new book about an interesting character.

That came out 20 years ago at the same time as my Invisible Woman. I don't think 20 years is any reason that you can’t. Just as you can always paint a new portrait of an interesting face, you can always write a new book about an interesting character.

Do you actually look at the previous biographies?

I am very friendly with Michael Slater - I admire him, I think he’s wonderful. He sent me a copy of his book [Charles Dickens, 2009]. I said, “Michael, I’m not going to read your book because I am writing my own. But I shall read it.” Let me say every now and then I turned to his book to see how he had handled some particular incident. But I didn’t use his book. Peter’s book I read when it came out and didn’t read it again. What I did use was John Forster’s great biography of Dickens. Years ago I bought a first edition of Forster and my three volumes are practically shredded by use. And I read a lot of the others. I knew Edgar Johnson, marvellous works by Philip Collins about Dickens. He wrote a two-volume book called Interviews and Recollections which is a goldmine of material. Una Pope-Hennessy wrote an interesting biography, George Gissing wrote a great book, GK Chesterton wrote a wonderful book. There is a marvellous Dickens literature. There are also all the barmy Dickens lovers who have tramped round everywhere Dickens ever went, and there’s The Dickensian magazine which is another goldmine. And so it goes on.

One of the great things about your book is that it is admirably brisk, without skimping. I imagine that part of the business of putting this book together was a question of editing.

I set out to avoid writing a huge, huge book. I tend to write short anyhow. My books tend to come out reasonably short and I didn’t want this to be a book that you’d have to take the breadknife to and saw in half before you read it. I have of course missed out various things but what I’ve tried to do is to give the life of Dickens the man, and the other thing I really wanted to do was to write about the books, because I think if you’re writing about a really great writer you really have to do that. And so I allowed myself that indulgence and I’m very glad I did because I really enjoyed doing that. It seemed very important to look very carefully at each of the books, particularly the ones I most admire, and say why I admire them, what I think their strengths are. I’m very proud of doing that.

You are bracingly frank about the defects of Hard Times and Barnaby Rudge in particular, and the second half of Dombey and Son. In which novel does Dickens most come closest in your opinion to perfecton? Which novel has the fewest bad bits?

He can’t do women in life and he can’t do women in books

I think Great Expectations is almost perfect. I think the condition of England novels, which are great baggy ones. You say I’m hard on Hard Times but I do say it perhaps has one of the most important statements Dickens ever wrote: “People must be amused.” Which he gives to Sleary of the circus. He has a lisp: “People mutht be amuthed.” And that is brilliant. Bleak House – you can find a page where it’s slack or silly but it is a great book. He imagines a world for each of his books. And those London novels - that and Little Dorrit which has a Shakespearean element in it, has poetry in it as Great Expectations has – they seem to me marvellous. I think Sketches by Boz is a great book. It’s not a novel but it’s the most extraordinary piece of observation and it tells you what Dickens had been looking at when he was growing up in London. So it actually gives us London in the 1830s. That account of the clerks walking into London – because of course they had to walk from the north suburbs, how the baker shops opened an hour earlier in the suburbs so they could buy their bread roll, and this great stream of humanity of all ages going into the city into the law firms – it’s an amazing picture. And the picture of the little girl released from prison and child prostitutes, a boy pickpocket being tried who later turned up as the Artful Dodger. That book also has some very funny stories in it.

Are the bad areas of Dickens usually associated with the fact that he is essentially a sexless writer, not in the sense that he is without gender but that he can’t write about women?

He can’t do women. He can’t do women in life and he can’t do women in books. He can do funny women, he can do ridiculous women, he can do awful old bags. But he had a problem. When he went up to be made Freeman of Edinburgh very early in his career the one thing Christopher North who did the eulogy said was, “There’s one thing he can’t do: he can’t do young women.” He was spot on.

There is a lovely moment when he’s in Paris and thinking about writing A Tale of Two Cities where he says that he envies Balzac and Hugo for the freedom they enjoy to be able to write about that which...

...the English novelist can’t. He and Thackeray both made that complaint: they can’t say what it’s really like to be a young man growing up.

Is his failure to put real women on the page to do with Victorian mores or do we also blame Maria Beadnell, the girl who rejected him when he was a young man and, by his own admission, hardened his heart?

Oh no, I don’t think we blame Maria Beadnell. In fact, he puts her wonderfully on the page. I mean actually two of his best women are Dora [in David Copperfield] and Flora Finching [in Little Dorrit]. (Pictured left, Ruth Jones as Flora Finching in the BBC's Little Dorrit.)

Oh no, I don’t think we blame Maria Beadnell. In fact, he puts her wonderfully on the page. I mean actually two of his best women are Dora [in David Copperfield] and Flora Finching [in Little Dorrit]. (Pictured left, Ruth Jones as Flora Finching in the BBC's Little Dorrit.)

He puts her well on the page but all the other women...

That’s true. Dreadful fluttering little creatures.

I’m thinking also of all the cold-hearted women – Edith Dombey or Lady Dedlock. Was he drawn to them too?

I don't think that Catherine was cold. She was always there, docile in the double bed. And in a way I think Nelly kept him as she did keep his affection and love by being difficult, alternating enthusiasm and withdrawal. So maybe he quite liked it. But that’s speculation and we don’t know.

With Nelly did he look for something to compensate for what he lacked in his marriage?

No, I don’t think he went looking. I think he was absolutely knocked over. I think he did fall in love with her and her sisters. He loved girls with sisters. And then she didn’t accept his sexual advances so then he was hanging about wooing her and then she did and there was the pregnancy in France and he went through all sorts of traumas, I think.

Continued overleaf: 'People didn’t like to think that a great man was an adulterer', plus the trailer to An Invisible Woman

Why have the Dickensian mob warned people in your trade off Nelly Ternan over the years? Why has she been such a dangerous topic for the Dickens Society?

That’s no longer so, I think. The family was protecting his reputation. People didn’t like to think that a great man was an adulterer obviously. We’ve forgotten how dreadful it was.

Except that, as described in your book, they were all at it in his circle.

Secretly, absolutely. Two households and two families – [Wilkie] Collins, [George] Cruikshank. But Dickens wasn’t like that. Dickens was the great emblem of domestic happiness. He’d written A Christmas Carol where Scrooge is reformed and becomes a loving family man. He was seen to be this marvellous, cheerful, jolly, home-loving man. And he did for years have wonderful Christmas parties with his children, everyone dancing, he did conjuring tricks, great feastings and cakes and jollity. And that’s what he stood for in the eyes of the public. And he could not afford to lose the love of the public. Not only did they give him love but they provided him with an income and he needed money to maintain his old mother and his widowed sisters-in-law and his wife and his mistress and her sisters. He needed money. But then the Dickensians later all got sort of angry about it and some of them who were scholars like Kathleen Tillotson said, “The only thing that matters are the books so we don’t want all this gossip.” There was that attitude. It was perfectly accepted by scholars such as Philip Collins and Una Pope-Hennessy who wrote about Dickens in the Forties and Fifties that there was a love affair. It was actually Peter [Ackroyd] who put forward this wonderful idea that it was an unconsummated relationship. It was Peter’s invention actually. Now it’s true that none of us know absolutely for certain what happened.

What do you make of his bizarre fascination with morgues, which is very, very strange...

Very strange indeed.

And prowling through the night, seeking out prostitutes not only to rescue them. One suspects reading between the lines of some of his letters that his fascination with that world was not entirely innocent. (Pictured below, Lionel Bart's image of Dickens's idea of a prostitute: Shani Wallis as Nancy in Oliver!)

What I’ve tried to say in the book is that I think it’s perfectly possible that he slept with a few prostitutes as a very young man. He has that conversation with Emerson who says that all young men are chaste in America and he says that he would be seriously worried if his son didn’t... I don’t think he was a frequent consorter of prostitutes but when Nelly turns him down he seems to get some sort of venereal disease. There’s a letter where he says, “I shall go my own wild way.” His setting up of the Home for Homeless Women was absolutely genuine. Dickens was able to do this, to separate things. That really was a magnificent, extraordinary venture that he believed in. Whatever sexual interest he might have had in those bedraggled girls who were being treated very well, not preached at and not made to take up religion but given nice clothes and beds and a little bit of garden, I think he really wanted to give them a chance. He cared passionately about people who were ill-used and had been rejected by society.

What I’ve tried to say in the book is that I think it’s perfectly possible that he slept with a few prostitutes as a very young man. He has that conversation with Emerson who says that all young men are chaste in America and he says that he would be seriously worried if his son didn’t... I don’t think he was a frequent consorter of prostitutes but when Nelly turns him down he seems to get some sort of venereal disease. There’s a letter where he says, “I shall go my own wild way.” His setting up of the Home for Homeless Women was absolutely genuine. Dickens was able to do this, to separate things. That really was a magnificent, extraordinary venture that he believed in. Whatever sexual interest he might have had in those bedraggled girls who were being treated very well, not preached at and not made to take up religion but given nice clothes and beds and a little bit of garden, I think he really wanted to give them a chance. He cared passionately about people who were ill-used and had been rejected by society.

And yet there’s that lovely glimpse of him in Paris one night noting a prostitute with a particularly alluring face and he wants to go back and find her and imagines that he never will.

Yes, he does say that, it’s true. I suppose he would like to talk to her. He wanted to practise his French.

When the partition goes up in the bedroom do you as his biographer simply have to stand aside and record it or is there not a part of you, especially as a woman, that is profoundly angered by this extraordinary and highly concrete gesture?

I think you don’t have to be a woman to be shocked by the way Dickens behaved at that time. As this story unfolds, you want to avert your eyes at quite a lot of things that he did at that time. I find it extremely painful. His daughter Katey, who often was right, said, “My father behaved like a madman.” But one advantage of being a very old biographer is you live through a lot. Perhaps most of us at one time or another in our lives have behaved like a madman or madwoman. That happens in life, and this very banal thing of being in a marriage and perfectly comfortable, and then suddenly people do get knocked sideways.

It’s relieving to hear that he does complain of Catherine having jealous rages, that suddenly you have a glimpse of her not being this doormat and is actually capable of having a flying temper.

But not enough. Not enough. In a marriage there’s a certain amount of space and Dickens took up that much space [Tomalin semaphores a lion’s share]. Catherine had no role really.

Do you think that she ever helped to name the children?

No, I don’t think so. Charley, of course, was the adored eldest son. Then Mary was named after her sister, Katey was named after her, and then after that they were all literary friends of Dickens’s: Alfred D’Orsay Tennyson Dickens.

Plainly the relationship with Mary Hogarth was profoundly unsettling but the longer-lasting relationship was with the younger sister-in-law Georgina. Is it not a very puzzling relationship?

Dickens writes about this in his novels. Traddles [in David Copperfield] had all the sisters of his wife. Dickens loved having the sisters about. He was attracted to families of sisters. Georgina was 15, 16, when she became part of his household, she was very bright but uneducated, and he formed her and she adored him. She was his little pet. And she had the much stronger will and, of course, she wasn’t pregnant all the time. He talked about “my two petticoats” – they went everywhere, the three of them, and he asked her to do things for him in a way that he never did with Catherine. In France he asked her to choose the villa, she could decide about the flat in Paris.

If he was so fond of bevies of sisters, do you think part of his disappointment with his family was that he just had this army of boys coming out of his wife’s womb?

Absolutely. And he says, after he’s had the third child Katey, "That’s it, I don’t want any more.” But he did like them when they were babies – the silly names for them and games and conjuring tricks. And then when they got to be clumping boys he really couldn’t deal with them and they were sent off to this awful boarding school in Boulogne. With Dickens’s view of awful boarding schools it’s very peculiar he gets rid of four of his sons.

One senses that it was not much fun being his children at all.

He adored [his first son] Charley even when Charley had gone bankrupt. He could never blame him and he loved the girls. And I think after that it was just too much for him.

Do you believe that Nelly genuinely loved Dickens?

I think if you’re a girl who’s grown up in poverty and you hardly remember your father and your mother and your sisters have all worked your socks off and you don’t really know what’s going to happen to you in life - and of the three sisters she was the last good actress - here appears this wonderful, jolly, ebullient, famous, generous man, and it’s just like Father Christmas. He was very good company when he felt like it and he helped the whole family. He didn't just go for Nelly. The Ternans became his other family. I should think she absolutely adored him because he was so kind and he adored her and that’s very hard to resist.

Katey Dickens virtually said this, that at the beginning it was good and it got less good as time goes by. At first also she hadn’t been brought up to fall into bed with someone she wasn’t married to so there was the crisis there. Then if, as I believe, she became pregnant there was a crisis there. And then as time went by - they lasted a long time: 12 and a half years - it wasn’t going anywhere and the sisters were married and she wasn’t and she was hidden and her life wasn’t too good, I shouldn’t think, just sitting waiting for someone to turn up. I think she made the best of it. She obviously did, as it were, turn herself into a quite striking person. She learnt to ride and she learned French and she read a lot. And he got older and iller. One of the things I didn’t know when I wrote The Invisible Woman which I did find out when researching this book is how much she obviously did want to go to America [with Dickens on his reading tour]. She wanted to have fun.

She made something of herself rather cannily after she was widowed. She married and lied to her husband about her age.

Absolutely, yes. She was like a phoenix rising from the ashes and she was absolutely recreated with the connivance of her sisters.

You seem to be persuaded that she had the child but you also suggest that one of the things that might have kept Dickens hanging on was that she was difficult.

You seem to be persuaded that she had the child but you also suggest that one of the things that might have kept Dickens hanging on was that she was difficult.

It’s all very conjectural. People who knew her later said that she had a temper, she had a will. Whether she showed this to Dickens, whether she made scenes... I imagine there were ups and downs and that possibly she was difficult and kept him on his toes. He seems to have expected to love her to the end. This is making bricks without straw but something about her held him, held his love and it’s so maddening that we do not have any of his letters or any account by her. It is a real problem for any biographer of Dickens. For this dominant element of the last 12 years of his life we have almost no reliable information about him. But we know it was so. There’s no doubt about it.

Are there characters in the novels in whom one can see her features delineated?

I don’t think her character was like Estella’s, probably, but the words he gives to Pip about his feelings for Estella are so powerful and so unlike anything else Dickens wrote about love it’s very hard not to think that to some extent he was describing his own feelings for Nelly, that he was helpless to do anything about them but he found her irresistible. (Pictured above: Martita Hunt as Miss Havisham with Jean Simmons as Estella in David Lean's 1946 film of Great Expectations). And then in Our Mutual Friend the character of Bella Wilfer is surely like a mixture of parts of his daughters and Nelly. He likes Bella Wilfer having fun with her father. She’s never very entertaining with her lover but with her father she flirts and teases and they go on these expeditions together and she winds her hair around him. Also Nelly’s background in a very poor household in north London, where the conditions are very elementary with not much to eat, you can’t help thinking that something about Bella has been taken from Nelly.

You have this intriguing suggestion he might have been very close to death while with Nelly in her house in Peckham.

I have gone through all that evidence again. I still think it is possible that he collapsed over at Nelly’s in Peckham and that Nelly realised how important it was to get him home. She had two maids to help her. I think it is possible. But I can see why people resist it because Georgina’s account is a very good account of his collapse at Gads Hill. But she was alone. Every account is taken from just Georgina’s say-so. And so I think it’s possible but I certainly don’t say I’m sure it’s so. That would be crazy.

I have gone through all that evidence again. I still think it is possible that he collapsed over at Nelly’s in Peckham and that Nelly realised how important it was to get him home. She had two maids to help her. I think it is possible. But I can see why people resist it because Georgina’s account is a very good account of his collapse at Gads Hill. But she was alone. Every account is taken from just Georgina’s say-so. And so I think it’s possible but I certainly don’t say I’m sure it’s so. That would be crazy.

The fact is that he did visit Nelly so regularly... He went to and fro and we know that he was doing that. From the 1867 diary the frequency of his visits is quite striking. And that we wanted her to go to America with him. He really wanted her in his life and also he wanted Gads Hill. And he wasn’t prepared to give up one for the other.

One could say of Georgina that she needed to create a scenario for his collapse and that she learned from the master.

They both did. Dickens was the master of deception. Nelly certainly became so after his death. Georgina was utterly devoted to Dickens and utterly devoted to his reputation. She was totally loyal and adoring. I think it’s possible that she and Nelly colluded. They went on being friends. When Georgina was a very old woman she was writing to Nelly’s children, who were on very warm terms with her. It is very odd. Everything is odd about Dickens.

- Charles Dickens: A Life by Claire Tomalin is published by Viking Penguin

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment