Elektra/Der Rosenkavalier, Nightly Met Opera Streams review - searing hits and indulgent misses | reviews, news & interviews

Elektra/Der Rosenkavalier, Nightly Met Opera Streams review - searing hits and indulgent misses

Elektra/Der Rosenkavalier, Nightly Met Opera Streams review - searing hits and indulgent misses

Challenging direction, great conducting and luxury casting in New York Strauss

A brutal Greek tragedy and a rococo Viennese comedy, both filtered through the eyes and ears of 20th century genius: what a feast on consecutive nights from the Metropolitan Opera's recent archive.

Loy is a radical re-thinker, usually with startling results, though he tripped up with his recent La forza del destino; and I wonder if he could have come close to the organic reinvention of the late, great Patrice Chéreau, whose production came to the Met three years after his untimely death (★★★★★). Perhaps the film of the original 2013 Aix staging, with the electrifying Evelyn Herlitzius as the protagonist and Chéreau on hand to inspire, will always have prior place as one of the top opera films of all time (it's still available on BelAir). But this alternative also boasts the fiercely analytical but never chilly conducting of Esa-Pekka Salonen, let loose on the magnificent Met Orchestra, and Stemme's Elektra is as much to be seen and heard as Herlitzius's.  Only total conviction and the willingness to sacrifice a dramatic-soprano voice on the altar of a killer role will do, and she offers both. Close-ups are welcome to see the tragic fixity, mania and sadness in those wonderful eyes as the daughter of Agamemnon, worn down and driven to the brink of sanity, awaits the return of her brother Orestes to avenge the murder of their father by their mother Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus. Despite late appearances by a solemn, mask-like Orestes - resplendently sung by the wonderful Eric Owens - and the thoroughly unpleasant Aegisthus - Burkhard Ulrich playing it straight as Chéreau asks all his singer-actors to do - this is an opera for strong women. There's even major casting among the maids whose squabble starts the action, here bowling into vicious musical life after much courtyard scrubbing and brushing; the Fifth Maid, defending the hated Elektra, is sung, as she was at Aix, by the great Roberta Alexander, one of the great Jenůfa of our time.

Only total conviction and the willingness to sacrifice a dramatic-soprano voice on the altar of a killer role will do, and she offers both. Close-ups are welcome to see the tragic fixity, mania and sadness in those wonderful eyes as the daughter of Agamemnon, worn down and driven to the brink of sanity, awaits the return of her brother Orestes to avenge the murder of their father by their mother Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus. Despite late appearances by a solemn, mask-like Orestes - resplendently sung by the wonderful Eric Owens - and the thoroughly unpleasant Aegisthus - Burkhard Ulrich playing it straight as Chéreau asks all his singer-actors to do - this is an opera for strong women. There's even major casting among the maids whose squabble starts the action, here bowling into vicious musical life after much courtyard scrubbing and brushing; the Fifth Maid, defending the hated Elektra, is sung, as she was at Aix, by the great Roberta Alexander, one of the great Jenůfa of our time.

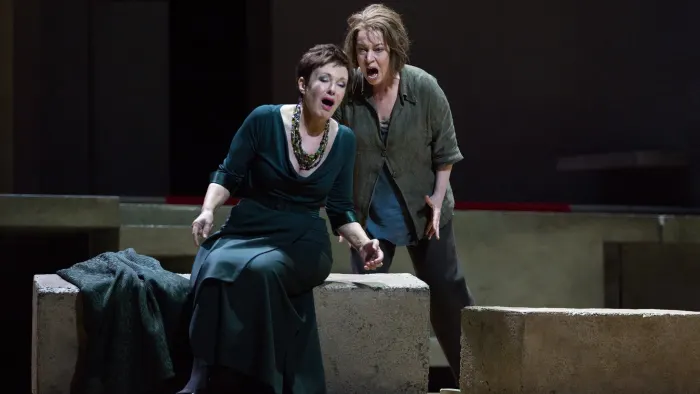

Chéreau makes sure the house staff are present at crucial stages of the action, but that doesn't undermine the essential isolation of the three female leads. All work at top vocal and dramatic pitch. Adrianne Pieczonka (pictured above with Stemme) is no weak sister Chrysothemis; it's just a question of Elektra being even stronger, and determined to the point of insanity. Lyric warmth with backbone meets pure steel - and both women hit the high notes with infallible focus. You might at first have to swallow the idea of their being offspring of this still-beautiful Clytemnestra, Waltraud Meier (pictured below with Stemme); but the central confrontation between mother and daughter is riveting. Chéreau makes much more of their need to be loved by each other than most directors, which only makes Elektra's turn of the screw all the more appalling. Meier, always a convincing stage animal, is also in remarkably good voice.  The denouement, static rather than turbulent with a convincing final pay-off, may be counter-intuitive to the welter of orchestral sound in what has to be the most overwhelmingly visceral operatic finale ever (Wagner notwithstanding). But it works, which is more than can be said for the final curtain and some of the other ideas in Robert Carsen's Der Rosenkavalier (★★★), not many of them convincing substitutions for poet-playwright Hugo von Hofmannsthal's elaborate original stage directions. Since Carsen first staged the work for Salzburg - there's another fine DVD, with Pieczonka as a sensuous Marschallin - he seems to have upped the luxury, partly perhaps to fill the big Met stage. It's a truthful idea to have the women of this opera dwarfed by images of male pride in portrait and frieze, but the first act can never be the chamber opera it essential aims to be, and nouveau-riche Faninal's forecourt with its obstructive cannons is only compounded for unhelpfulness by the pointless waltzing couples in the Presentation of the Rose. The Act Three brothel is more successful as a mirror-image of the Marschallin's bedchamber; the biggest laughs come here.

The denouement, static rather than turbulent with a convincing final pay-off, may be counter-intuitive to the welter of orchestral sound in what has to be the most overwhelmingly visceral operatic finale ever (Wagner notwithstanding). But it works, which is more than can be said for the final curtain and some of the other ideas in Robert Carsen's Der Rosenkavalier (★★★), not many of them convincing substitutions for poet-playwright Hugo von Hofmannsthal's elaborate original stage directions. Since Carsen first staged the work for Salzburg - there's another fine DVD, with Pieczonka as a sensuous Marschallin - he seems to have upped the luxury, partly perhaps to fill the big Met stage. It's a truthful idea to have the women of this opera dwarfed by images of male pride in portrait and frieze, but the first act can never be the chamber opera it essential aims to be, and nouveau-riche Faninal's forecourt with its obstructive cannons is only compounded for unhelpfulness by the pointless waltzing couples in the Presentation of the Rose. The Act Three brothel is more successful as a mirror-image of the Marschallin's bedchamber; the biggest laughs come here.  Nevertheless the core comedy doesn't come off very well; Carsen seems to want to make the coarse adventurer Baron Ochs more real than funny-grotesque, and Günther Groissböck tries to compensate by flapping around the giant space in an attempt to fill it. The biggest disappointment, for me, is Renée Fleming's Marschallin (pictured above with Elina Garanča; both Rosenkavalier images by Ken Howard), the character with whom, as Hofmannsthal put it, the audience should identify most sympathetically; men as well as women beyond the age of 30 have all been there to share, if not as articulately, her worries and questions about the passing of time and the takeover of the young. The voice still glows, but at full stretch it can't be coloured to create a sense of introspection; and though this interpretation is not as vulgar or indulged as Fleming's former complicity with Christian Thielemann, she still takes the stop-all-the-clocks monologue and the first phrase of the great final trio way too slow, to show off what she can do with breath control. Less would always be more, faster tempi always preferable.

Nevertheless the core comedy doesn't come off very well; Carsen seems to want to make the coarse adventurer Baron Ochs more real than funny-grotesque, and Günther Groissböck tries to compensate by flapping around the giant space in an attempt to fill it. The biggest disappointment, for me, is Renée Fleming's Marschallin (pictured above with Elina Garanča; both Rosenkavalier images by Ken Howard), the character with whom, as Hofmannsthal put it, the audience should identify most sympathetically; men as well as women beyond the age of 30 have all been there to share, if not as articulately, her worries and questions about the passing of time and the takeover of the young. The voice still glows, but at full stretch it can't be coloured to create a sense of introspection; and though this interpretation is not as vulgar or indulged as Fleming's former complicity with Christian Thielemann, she still takes the stop-all-the-clocks monologue and the first phrase of the great final trio way too slow, to show off what she can do with breath control. Less would always be more, faster tempi always preferable.  Which Sebastian Weigle, who's given us fine Strauss in Frankfurt, usually observes; he would seem to be indulging his Prima Donna. At least Elina Garanča is perfect as Cherubino-alike Octavian, the Marschallin's 17 year old lover whom she eventually has to yield. Here's one of the few occasions where one can believe in "him" as a stroppy, mostly self-confident youth. Erin Wall (pictured above with Garanča), like Clytemnestra's Met daughters, is palpably older than innocent teenager Sophie, but she has a face of very original beauty, used to express full fledgling feistiness, and she has all the money notes; I'd love to see her as Strauss's Arabella or Daphne. And despite the reservations over interpretation, this is as classy in musical terms as Strauss can get; you can never do these productions on the cheap. Let's hope the Royal Opera and the Met can come back soon to give the unique thrill of a hundred-or-so-piece orchestra and the world's best voices in the flesh.

Which Sebastian Weigle, who's given us fine Strauss in Frankfurt, usually observes; he would seem to be indulging his Prima Donna. At least Elina Garanča is perfect as Cherubino-alike Octavian, the Marschallin's 17 year old lover whom she eventually has to yield. Here's one of the few occasions where one can believe in "him" as a stroppy, mostly self-confident youth. Erin Wall (pictured above with Garanča), like Clytemnestra's Met daughters, is palpably older than innocent teenager Sophie, but she has a face of very original beauty, used to express full fledgling feistiness, and she has all the money notes; I'd love to see her as Strauss's Arabella or Daphne. And despite the reservations over interpretation, this is as classy in musical terms as Strauss can get; you can never do these productions on the cheap. Let's hope the Royal Opera and the Met can come back soon to give the unique thrill of a hundred-or-so-piece orchestra and the world's best voices in the flesh.

- Though both productions are no longer available on the nightly free stream, they can still be seen in the Met's Opera on Demand series

- The Met's free nightly opera streams continue. Full list here

- .Read more opera reviews on theartsdesk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Add comment