Bodies, Southwark Playhouse review - shaky revival misses the mark | reviews, news & interviews

Bodies, Southwark Playhouse review - shaky revival misses the mark

Bodies, Southwark Playhouse review - shaky revival misses the mark

Last seen 40 years ago, James Saunders' four-hander never quite gets off the ground

Bodies is the latest in Two's Company's series of what they deem "forgotten masterworks", this one making a less-than-triumphant return to the London stage after almost 40 years away. Written by James Saunders in 1977, it opened at the Orange Tree in Richmond before transferring to the Hampstead Theatre and then on to the West End.

Husband and wife Anne (Annabel Mullion) and Mervyn (Tim Welton) invite their old friends David (Peter Prentice) and Helen (Alix Dunmore), back in Blighty after a spell in the States, round for dinner. It's been nine years since the couples have met, which could have something to do with Anne's affair with David, and Helen and Mervyn's subsequent fling. Surely if the play had been written today they'd have all ended up in a polyamorous quartet.

But modernity is indeed present, in the form of the revolutionary new therapy David and Helen have undergone since their sort-of friends last saw them. This seems to be something like what we now call mindfulness; the idea is to let go of the past and the future and exist solely in the present. Happiness and unhappiness are equally false: nothing but shadows on the walls of the cave. All that matters is the self. This, of course, horrifies Mervyn and Anne.

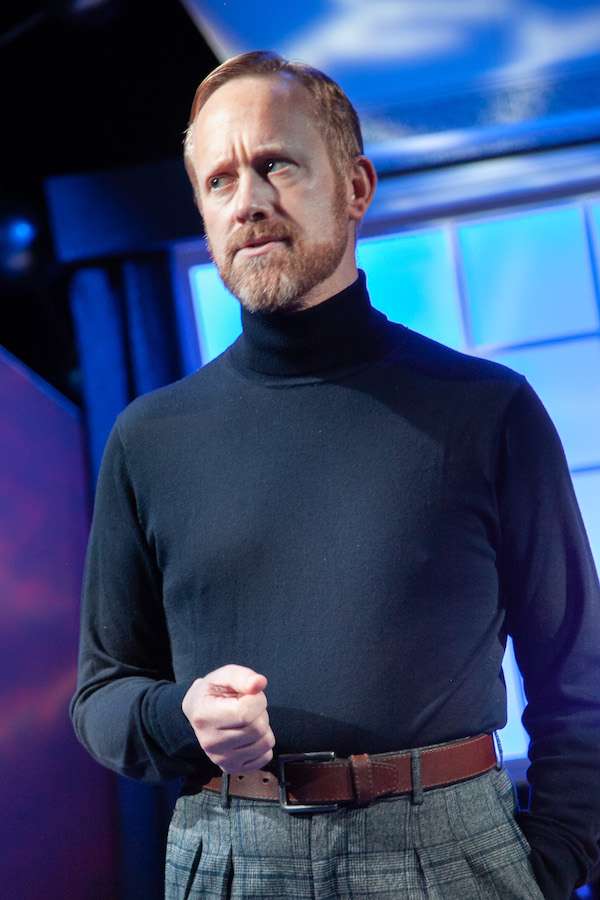

The first half is mostly made up of each character taking their turn to deliver one or another monologue about the past, which, with the exception of Welton (pictured below), the actors don't quite nail. It's acting by numbers: they seem to have such a clear idea of the pacing of their long speeches that the words almost become a vehicle for hitting the beats. It doesn't help that the words themselves are, in general, dull. In the interest of full disclosure, I was born after this play was written, so maybe it's a generational issue. But for a production which, like all revivals, proudly announces its relevance to the present day, Saunders' play just doesn't make enough of a case for itself. (The playwright died in 2004.) The second half is much better, largely because the four are finally allowed in a room together. Tempers fray as an increasingly tipsy Mervyn prods at Helen and David's newfound happiness, searching fruitlessly for a chink in the armour. Welton is one of the few actors who can play drunk convincingly. Again, he's the best of the bunch, helped by the fact that his character has the most to do; act two is uneven in terms of line-sharing, with the men doing most of the talking. But the other three do perk up a bit, especially Prentice (pictured below right), who takes on an air of barely controlled rage, as if he's about to bludgeon everybody to death with his coffee cup.

The second half is much better, largely because the four are finally allowed in a room together. Tempers fray as an increasingly tipsy Mervyn prods at Helen and David's newfound happiness, searching fruitlessly for a chink in the armour. Welton is one of the few actors who can play drunk convincingly. Again, he's the best of the bunch, helped by the fact that his character has the most to do; act two is uneven in terms of line-sharing, with the men doing most of the talking. But the other three do perk up a bit, especially Prentice (pictured below right), who takes on an air of barely controlled rage, as if he's about to bludgeon everybody to death with his coffee cup.

At two and a quarter hours including interval, the play feels too long, and begins to drag three-quarters of the way through each act. That's not to say there aren't any good bits. "These," David says at one point, holding up his hands, "are dishwashers." No, Anne corrects him, gesturing at herself and Helen: "These are dishwashers." Earlier, Anne reveals that her fundamental issue with Helen and Mervyn's affair is not the obvious – it's that he, a serial adulterer, has robbed her of her one attempt to get back at him. And Mervyn's problem with Helen and David's way of life – one that focuses entirely on the here and now, the immediate physical body – is heart-breaking in its own way. "If the body is all there is," he laments, tears in his eyes, "then there's no room for art." And Mervyn needs there to be room for art: he's an English teacher-turned-headmaster, and if art is nothing, so is he.

At two and a quarter hours including interval, the play feels too long, and begins to drag three-quarters of the way through each act. That's not to say there aren't any good bits. "These," David says at one point, holding up his hands, "are dishwashers." No, Anne corrects him, gesturing at herself and Helen: "These are dishwashers." Earlier, Anne reveals that her fundamental issue with Helen and Mervyn's affair is not the obvious – it's that he, a serial adulterer, has robbed her of her one attempt to get back at him. And Mervyn's problem with Helen and David's way of life – one that focuses entirely on the here and now, the immediate physical body – is heart-breaking in its own way. "If the body is all there is," he laments, tears in his eyes, "then there's no room for art." And Mervyn needs there to be room for art: he's an English teacher-turned-headmaster, and if art is nothing, so is he.

There are other flickers of brilliance but just not enough of them, especially in the first act. Saunders' lines of reasoning are all over the place, which is perhaps the point but still makes for a rather inscrutable evening.

An audience member was heard to remark, upon leaving the theatre, that "they don't make 'em like that any more". He was spot-on – and thank heavens for that.

- Bodies at Southwark Playhouse until 9 March

- Read more theatre reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Add comment