The American Clock, Old Vic review - Arthur Miller's musical history lesson drags | reviews, news & interviews

The American Clock, Old Vic review - Arthur Miller's musical history lesson drags

The American Clock, Old Vic review - Arthur Miller's musical history lesson drags

Rachel Chavkin's creative revival can't quite tame this sprawling epic

This year’s unofficial Arthur Miller season – following The Price and ahead of All My Sons at the Old Vic and Death of a Salesman at the Young Vic – now turns to his 1980 work, The American Clock, inspired in part by Miller’s own memories of the 1929 Wall Street Crash and subsequent Great Depression.

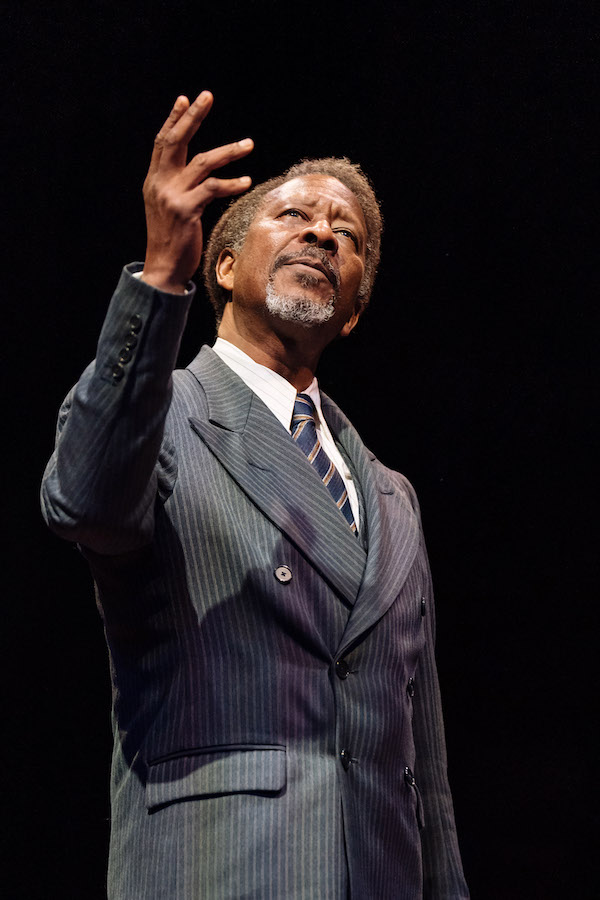

Central to the play is the Baum clan: father Moe, initially a hotshot businessman; wife Rose, who adores musicals and whose piano is her refuge; and son Lee, Miller’s loose alter ego, who dreams of being a writer. When the crash hits, the Baums are forced to swap their spacious Manhattan home for cramped Brooklyn quarters. We also glimpse, among others, rioting farmers and suicidal stockbrokers – introduced by the excellent Clarke Peters’ all-seeing narrator (pictured right). Plus this history lesson examines Roosevelt’s New Deal, the tantalising rise of communism, and the competing swell of fascism.

Central to the play is the Baum clan: father Moe, initially a hotshot businessman; wife Rose, who adores musicals and whose piano is her refuge; and son Lee, Miller’s loose alter ego, who dreams of being a writer. When the crash hits, the Baums are forced to swap their spacious Manhattan home for cramped Brooklyn quarters. We also glimpse, among others, rioting farmers and suicidal stockbrokers – introduced by the excellent Clarke Peters’ all-seeing narrator (pictured right). Plus this history lesson examines Roosevelt’s New Deal, the tantalising rise of communism, and the competing swell of fascism.

Miller’s play was initially a flop on Broadway, but better received in a 1986 National Theatre version that came closer to the intended vaudevillian mosaic. It’s since been constantly reworked, and American director Rachel Chavkin – responsible for the wonderfully organic productions of musicals Hadestown and Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812 – now puts her distinctive spin on it.

Staging wise, there’s an immediate engagement, with the Old Vic reconfigured in traverse and part of the audience seated onstage. The central revolve of Chloe Lamford’s set facilitates fluid, dynamic movement, an ever-present jazz band lends excellent support, and there are some strong theatrical flourishes, like towering chalkboards proclaiming stock prices, the grand piano so beloved by Rose given great prominence, a soundscape mixing vintage and modern music (Justin Ellington and Darren L. West), and key radio announcements.

A recurring motif is the Depression-era dance marathons, in which contestants tried desperately to outlast one another for a cash prize; choreographer Ann Yee provides energetic swing. It’s a clever runner, showing how entertainment could be warped into something sadistic in hard times, but also demonstrating a resilient, optimistic spirit that Miller’s piece identifies as intrinsically American. Music also plays an expressive part throughout Chavkin’s production, with Golda Rosheuvel in particularly fine voice.

Other choices work less well, such as the triple-casting of the Baum roles, with different actors playing the family members in later phases of their lives – Jewish white, South Asian and African-American, to reflect waves of immigration. It doesn’t really aid the drama (although all, pictured below, inhabit the roles well), nor match up thematically, and adds to the confusion of a play teeming with characters – many of whom only appear briefly, or with long stretches in between their scenes. But the major difficulties reside in Miller’s polemical text, which hammers home its points about the flaws of capitalism relentlessly – as well as demonstrating the decade’s hardships again and again. Adding tap dancing livens up the resigning General Electric boss’s tirade, but can’t disguise its bluntness. Most irritating is Clarke’s narrator directly asking Lee how all of this makes him feel, rather than illustrating the latter’s growing disillusionment through drama.

But the major difficulties reside in Miller’s polemical text, which hammers home its points about the flaws of capitalism relentlessly – as well as demonstrating the decade’s hardships again and again. Adding tap dancing livens up the resigning General Electric boss’s tirade, but can’t disguise its bluntness. Most irritating is Clarke’s narrator directly asking Lee how all of this makes him feel, rather than illustrating the latter’s growing disillusionment through drama.

There are also, however, some stirring human moments, vividly captured by Chavkin’s production. One of the most gripping scenes sees a conflict between now debt-ridden Iowa farmers and the judge come to auction off their farms escalate suddenly. There’s also the all-too-resonant tales of adult children forced to move back in with their parents, the struggle for the previously affluent Baums to pay for college, and, at the dire end, chronic unemployment and homelessness – all because a nation subscribed to an idea that proved catastrophic.

Among a tireless ensemble, Rosheuvel is powerful as the final, crumbling Rose, plus an urgent advocate for socialist solidarity; Fred Haig lends sweet voice to the younger Lee; James Garnon supplies two key authority figures in unusual positions; and the superb Francesca Mills becomes the heart of the piece, her roles including the painfully innocent sister of a suicidal broker, a landlady’s daughter whose engagement is semi-transactional, and a passionate communist comic-strip artist challenging Lee’s cynical apathy. Yet this stinging indictment of the American Dream, despite a robust revival and chilling modern parallels, lacks the dramatic vitality of Miller’s best work.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

50 First Dates: The Musical, The Other Palace review - romcom turned musical

Date movie about repeating dates inspires date musical

50 First Dates: The Musical, The Other Palace review - romcom turned musical

Date movie about repeating dates inspires date musical

Bacchae, National Theatre review - cheeky, uneven version of Euripides' tragedy

Indhu Rubasingham's tenure gets off to a bold, comic start

Bacchae, National Theatre review - cheeky, uneven version of Euripides' tragedy

Indhu Rubasingham's tenure gets off to a bold, comic start

The Harder They Come, Stratford East review - still packs a punch, half a century on

Natey Jones and Madeline Charlemagne lead a perfectly realised adaptation of the seminal movie

The Harder They Come, Stratford East review - still packs a punch, half a century on

Natey Jones and Madeline Charlemagne lead a perfectly realised adaptation of the seminal movie

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

Add comment