theartsdesk Q&A: guitarist Sean Shibe | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: guitarist Sean Shibe

theartsdesk Q&A: guitarist Sean Shibe

A wise head on young shoulders questions the nature of expression and programming

First it was the soft acoustic guitar playing, which on three occasions to three very different audiences won a silence so intense it was almost deafening.

There's more than a touch of creative genius in all this, and as Graham Rickson confirmed in this week’s Classical CDs Roundup on theartsdesk, the new softLOUD CD highlights that even more than Edinburgh-born Shibe's debut disc of English guitar music.

I've encountered this modest but sure-of-himself young thinker and performer – still only 26 – at several small-scale festivals; we talked before lunch at the Frontline Club in Paddington between the releases of his two Delphian discs.

DAVID NICE: You were playing a wide range of repertoire at the East Neuk Festival, but we can't really call the development crossover, can we?

SEAN SHIBE: No, so much of what is called crossover just seems to me really crass; the attempt to break down genres can be very unhealthy, if done badly. That programme I did in Anstruther, don't bother calling it crossover any more, it's all just really good music.

Friends of mine went to the show on the Edinburgh Fringe, and they were wildly enthusiastic, but they did feel they needed the earplugs.

Yes, the sound technician got a bit naughty towards the end, he was pushing the boat out.

Was it a different sound set-up from Anstruther?

Yes, it was. The BBC did have quite a bit of input there. They were setting up for three or four hours before the sound technician arrived.

I'd still love to hear some of it in a big space, even a cathedral perhaps.

It's hard, because the music's quite pure, in places too reverberant: it can become very muddy very quickly, so we had a very dry space in the Fringe that worked very well. It was interesting to see the audience reactions too – a couple of people came because they thought it was just a classical guitar recital...

Well, they got some of that. You offer people a chance to open up and if they can't, that's their problem.

You just have to express what you feel is authentic, so long as people understand that..

You have strong politicial views.

You have strong politicial views.

With my softLOUD project there was a political leaning – but I'm not writing an anti-Brexit programme note, I just want people to think a little bit more – I don't expect people who come to my concerts to be converted to a different cause; I'll be happy if perceptions are just a little bit altered.

When you speak in concerts, you don't push things on people – rather like Barenboim's speech at the Proms, it wasn't hardcore anti-Brexit, it was about education.

You have to be quite nuanced. After Bataclan and all these atrocities which are happening every couple of months, I saw these memes of Bernstein on Facebook, from a letter after the assassination of JFK, wiriting that the artist's response to violence should be to play music more beautifully and more tenderly and more passionately than ever before, and that's a great starting-point. But I feel that the problems we face are so pointed and precise that there should be a more articulated musical response to make, so that's kind of the direction that I felt forced to make, to do something more urgent and pointed..

In what way, specifically?

Pointing towards anger and a specific kind of language that's been lost, like tenderness and humility and profundity within those qualities as well..

Not just, as MacMillan said, having an instant spiritual high, but a high that comes out of conflict and anger; if you look at the big 20th century symphonies, Nielsen and Shostakovich, they’re all about that.

The guitar is renowned for this plethora of 19th century Spanish miniatures, really sweet pieces, good pieces, but somehow in this age of Trump and Brexit and nationalistic politics, it seems a little disingenuous to play that music and think I’m really expressing something I feel, So when people come to a concert and they say, why don’t you play something like [Albéniz's] Asturias, it’s not appropriate for me right now. And it’s never been greatly nourishing to explore.

So what else would you pursue in terms of the angry? Do you have a mission?

You don’t have to be angry all the time…I want to explore more experience-driven things – I don’t have anything lined up. It’s why I want to explore more in terms of software-led sound structures that are in some way live and responsive to acoustic, physically inititated sounds. There’s a programme called Max MSP, where if you sound one note, another one follows, it’s really very sophisticated, and it can be experience-driven and location specific as well. I have a friend who’s in quite a good band based in Glasgow called Pinact, we were at high school together, he was complaining about classical music and saying, what are you really aiming for? You’ve got into a position where if you practice really hard you’ll maybe play this piece better or differently or at a similarly exceptional level to the way someone else has been doing before, and of course it’s not completely fair, but – what are we really doing? Do we want to be playing music better than the previous person, or differently? Is that enough? I think it’s enough for some people, and some people do it really well, believe in it, but I…

But if you reach the highest level, it frees you up to do something in the performance you may not have done before. There's a new move for orchestral musicians, for instance, to play works from memory.

Here we’re talking about something broader, which is, what’s the point of musical expression? I feel bands have often been much more politically urgent and progressive than classical performers, and I don’t think it has to be that way, so beginning to programme in a different way is the start of this journey to try and pick up more. Saying to become more relevant makes it sound a little contrived and cynical, but there’s an urge to be more cutting.

On YouTube there are several films of you playing Villa-Lobos when you were 16 or 17 and it seemed you were pretty complete as a performer then. How do you feel it’s evolved in 10 years? Were you always serious at the start?

On YouTube there are several films of you playing Villa-Lobos when you were 16 or 17 and it seemed you were pretty complete as a performer then. How do you feel it’s evolved in 10 years? Were you always serious at the start?

I was as serious then as I am now. Maybe when you’re younger it’s just something you do and you’re better at it than other people are, and you carry on for that reason. I feel like I’ve become more into colour. To be honest, I’ve always struggled with the guitar as an instrument. OK, physically it’s hard but there’s not much volume, there’s not much to sustain or to project, you don’t have the qualities you should really need as a player of any instrument, so all you have is colour, to use this colour to coax the instrument into the illusion of colour. So when faced with the lack of those qualities, the lack of a really first-rate canon, mostly with repertoire from guitarist composers, there’s a feeling of insecurity and of, what’s the point, you know? But the magic is in the physicality of the instrument, being close to it and being able to strike it in a way that is unique in its proximity. So I’ve become more in touch with those qualities of the instrument, that’s something organic or esoteric.

You’re not dealing with what actually exists, you’re trying to pretend that something else exists, you’re like a magician, which is why the electric guitar is so interesting, it’s the opposite of that, you’re not implying these textural sonic universes, you’re literally able to create them as manifestation rather than implication. So getting more in touch with the classical guitar, that’s how I’ve become close to it and that’s what I feel my development has been, that every couple of months I feel, oh, I’m finally falling in love with this instrument. I feel I’m at a point now where I’m really happy with the way I treat it and I think of it conceptually.

There’s a push, and I feel it’s probably connected with the proliferation of competitions, that is necessarily part of the classical guitar career universe, it’s resulted in many makers making instruments that are extremely precise and very loud but not actually interesting in terms of the colours. When I listen to a lot of my contemporaries playing, I think that’s what really disappoints me, there’s not enough of what I think the guitar is, there’s a pretending that it’s like a piano or a harpsichord. It should be symphonic not in terms of what it can provide contrapuntally but in terms of the range of colours and textures. That's what I feel we should be heading for.

But that requires a completely silent audience, and that really struck me. The audience plays its part in the triangle of the composer, the performance and the audience.

And space, yes. The guitar is never going to be the most overwhelming instrument in terms of the volume it provides, so why bother going there when you can be extremely overwhelming in terms of the colour you provide. What shuts the audience up is when you’re conquering with this subtle palette of sounds.

You imply you didn’t really like the guitar when you were younger, so why did you play it? How did this happen?

I played cello for eight years or so, it took up a lot of time.

And was the cello seen as your first instrument?

Yes, people were encouraging, there was always – I enjoyed the physicality of the guitar. A lot of the rep was not really interesting. It may seem like a cool, objective explanation but I think it’s true that I'm continuing with that exploration of the physical nature of it, at a more rounded level. There are many routes to that.

Is there any connection with another craft, both your parents [Paul Tebble and Junko Shibe] being potters?

I’ve never gone for that one, but who knows? Why not? It does feel like weaving sometimes, there are so many delicate noises. It's a very fragile instrument, so exposed and so easy to make a sound that’s ugly. On the piano you have a lot of room, and on the guitar if you’re a millimetre out …it’s not as if the sounds vary and you can improve them with the bow, and if you push, you get a rasp.

What intrigued me is that a handful of pianists can make different sounds with left and right hands respectively, and in how they highlight the melody. You too are providing a layering of sounds…

Hopefully.

That struck me in the Villa-Lobos [a second-half programme of whose pieces Shibe presented at tenor Ben Johnson's Southrepps Festival in North Norfolk].

Great. I think again it’s colours and different colours at different overtones that can penetrate level, and so using something quite soft, which isn’t to say quiet, but then you don’t need to stretch the sound or find something that pierces the level, which is why I think it’s so important in providing an illusion of volume.

The repertoire – you’ve explored certain masterpieces like the Britten Nocturnal after Dowland, but there aren’t that many that are actually written for the guitar. Is that fair?

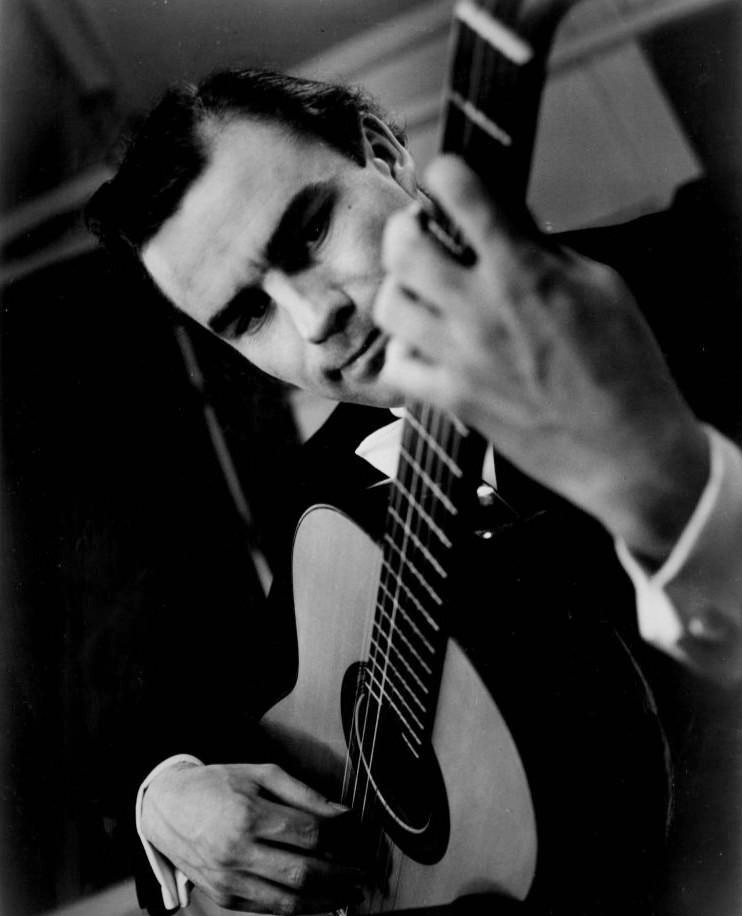

Julian Bream (pictured left), you mean. What does he think of you?

Sometimes he tells me, "that was the loveliest I’ve ever heard that piece played" and at others, "you don’t know how to interpret music. Just listen to John Williams, copy his recordings, that will make you better".

You shouldn’t copy anyone, should you?

Well, he’s not a great teacher, on his own admission.

The best are those that bring out the individuality of the person.

I couldn’t agree more – and I think Bream would agree, too. He says, I can’t tell you what to do.

You mentioned Segovia and I think you said you thought he was overrated.

I think he’s rated pretty accurately, I think you often hear more from the people who rate him very highly than the people who rate him not very highly.

It’s the legendary name.

There are still people in important positions who had personal relationships with him, and he was very important in their lives, and they have a lot of power. If you talk to younger players, a lot of them would say what I’m saying, which is that he’s a very complicated personality, often not a very nice man, often not a very good teacher; he was vastly important to the development of the guitar, and he achieved things that were very good first time. I'm open to being converted, but he’s just one of these players, you must come across them all the time, people say, this guy’s incredible, this guy really knows what he’s doing – you’re just trying all the time to understand what people are seeing in him, because they’re saying it so often, and I don’t get it.

It’s the same with some top singers – I’ve heard better in their last year at music college, but that’s partly to do with the industry and the marketing. Were there any guitarists who particularly influenced you, apart from Bream, or was it more from other fields?

You’re always having to make the guitar sing, and it’s not so easy.

Not so easy, no. So the pursuit of the qualities of vibrato you experience in the cello on the guitar is something you seek. Bream is undoubtedly some kind of influence, but that’s said so often by so many people that it’s almost worth not putting down as an influence. It's too complex to pinpoint what kind of influence he actually had. I’ve just always tried to be at home in what I’m creating, that I really adore. If you have an interpretation and you understand it so intimately that you believe that at this point, this is the only interpretation that should be given, that’s what I’m always aiming for, and I don’t always get to that narcissistic stage – you understand that it’s also false at the same time, you realise that there are so many interpretations that could be given, but you have to believe to that extent.

Where would you say you achieved that, in what pieces and where? Can you think of any examples?

Definitely the Nocturnal, I believed that, and Bach’s Prelude, Fugue and Allegro, there were things going on there that I absolutely believed; a lot of Dowland, definitely, sometimes in the Villa-Lobos, or at least I’ve known exactly where I’m going, I haven’t always reached the final point.

Again, programming that selection [at Southrepps], which seemed to mark a journey into increasing strangeness, supernaturally weird.

Yes, it’s utterly arcane, supernatural forces.

I love the ariettas in the Malcolm Arnold – that was a revelation to me.

It is fantastic music. So jagged and tormented at times.

Again the radiance is achieved…

Through that struggle. They’re exquisite, just beautiful little gems. Do you know Fiona Southey? She used to be his manager, I met her several times, she said, you know that was what Malcolm was like, he had this reputation of being someone who would really fly off the handle, but also took great care and had great sensitivity.

Are there people in other genres that affect the way you work, like pianists or even orchestras and conductors?

The place I’d like to spend more time at is the theatre, and I feel like that’s more the creative influence sometimes than other things.

In terms of presentation or context?

Yes, in quite a wishy-washy way. Theatre compared to cinema, if you’re having a dream and you’re watching something on television, you always have the innate danger of falling into another thing, that’s the thrill of the theatre – that you’re about to fall into this world, that’s why it feels more dangerous than cinema, so close, the proximity to that level of emotion, belief in that world – it urges me to try and create that more in musical terms.

So that the concert as a whole is more of a drama.

There should be a clear sense of narrative and progression, which I feel is often lacking. Even from really great players I sometimes come across programming, I’m talking pretty specifically about the guitar world, that I think is really unconstructive – I feel like we guitarists have so far to go in becoming sophisticated and worthy of recognition. There isn’t time to be conservative, that’s what I see a lot of. And I feel like the guitar is so vulnerable to a superficial, unnecessary kind of flash, because of the history of flamenco, and this kind of thing. It should never be too flashy or too comfortable.

Schoenberg said comfort is the enemy of creativity.

And I feel the guitar spends a lot of time doing the comforting and being the comforter.

You’re open to commissions – what about James MacMillan?

You’re open to commissions – what about James MacMillan?

Well, I’m at his festival at the end of this month, and we’ll see what comes. Mark Simpson says he might have some time at the end of this year, but Mark is a law unto himself, as are all composers, but the money’s there. Mahan Esfahani and I, I talk to him like he talks to a lot of people about commissioning works and with various combinations, that could also be a possibility. But again this is the beginning of something – commissioning pieces is not the end goal, like making a legacy – I want to create something broader, more experimental, more immersive. For his Cumnock Tryst festival, James has commissioned a work by Michael Murray, whom he came across in high school and traced him, found he was working as a security guard in a local shopping centre and writing music in his breaks. As I’m sure you know, James does a lot of outreach in schools. It’s interesting to read about him because in some ways he’s ultra-conservative, ultra-Catholic and writing for The Spectator, but on the other hand he just very quietly does all this engagement work in the community, in such an admirable and honest way.

You could make money playing Rodrigo's Concierto de Aranjuez all over the place – is that something that just doesn’t interest you?

No, I’ve just not done it that much, I played it last year a couple of times. I feel like my career is currently weird enough that there’s not a great danger of getting stuck with the Rodrigo. It’s not like I started with a disc of Spanish guitar music. To be quite honest with you, I’d quite like to do it more, in terms of pieces where I feel I’ve developed an artistic interpretation, a comfortable zone with, that’s one of them. I was very pleased with last year’s performance.

What about modern transcriptions? There are some things that would work with the guitar – I was thinking of Prokofiev’s Visions Fugitives. Things that wouldn’t be your territory normally.

Transcribing would be something. We'll see. The English guitar rep is unusual, because the usual is Spanish rep, but it’s standard guitar pieces, Walton, Dowland, we all go through that. There's a responsibility you have, a quality that has to be met, but I do feel I’ve lived with this rep for long enough that I’m really happy with what I created, to the extent that I’m actually surprised at how happy I am.

You’re obviously extremely self-critical.

Yes, which is why I feel comfortable about saying it. In a way the reason that I have recorded this music is partly because I’ve been frustrated by previous recordings. What I seek is a certain grasp of phrasing with colour, you often get one or the other but not both. And I'm working towards that.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914