Joan Sutherland: The Complete Decca Recordings - Operas 1959-1970 (Decca)

Joan Sutherland: The Complete Decca Recordings - Operas 1959-1970 (Decca)

The legend of "La Stupenda" was born at Covent Garden in 1959, when Joan Sutherland sang and – by all accounts – acted her socks off as Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. But she had been singing roles at the Royal Opera for seven years already – not just small parts but major ones such as Mozart’s Pamina and Countess, Verdi’s Desdemona and Amelia, Jenifer in the world premiere of Tippett’s The Midsummer Marriage and Mme Lidoine, the courageous new Prioress, in the UK premiere of Poulenc’s Dialogues des Carmélites. And as this mostly stupendous set shows, in the two years before she recorded her first complete Lucia, she shone in the studio as Handel’s Alcina and Galatea, Mozart’s Donna Anna and – to a lesser degree, as the brightness, not for the first or last time, seems to have been switched off – Verdi’s Gilda.

The starting point here was new to me, though Sutherland’s second Alcina of 1962 is better known, including Mirella Freni as Oberto and Teresa Berganza as Ruggiero. In both, Sutherland was encouraged to borrow from secondary soprano Morgana’s role, including the celebrated "Tornami a vagheggiar", and in the first, boasting surprisingly fine Handel style from conductor Ferdinand Leitner, the alto role went to a tenor; Handel would surely have been fine with that since it’s the great Fritz Wunderlich. Peter Pears is her unlikely swain in the Acis and Galatea, Luigi Alva the other half of a fragile and touching pair in the Giulini Don Giovanni, still one of the best (even Schwarzkopf is tolerable here).

Many of the Italian operas Sutherland returned to in the 1970s have a slightly recessed stage picture for the voices, and her most celebrated tenor partner, Luciano Pavarotti, doesn’t appear on the scene until Beatrice di Tenda in 1966. The standouts are the first Traviata, with Bergonzi, sound notwithstanding, Semiramide and Norma with her other great companion Marilyn Horne, and then on to La fille du régiment , showcasing her gift for sometimes uproarious comedy (plus Pavarotti on the famous high Cs; he’s also on the rather lovely L’elisir d’amore) and the wonderful Lakmé with the ideal tenor for the lyric French repertoire, Alain Vanzo (Franco Corelli is a fascinating choice in Gounod’s Faust, but not quite idiomatic). The others I rank in the same league, including some surprise choices of repertoire, will have to wait until the last of the three boxes. - David Nice

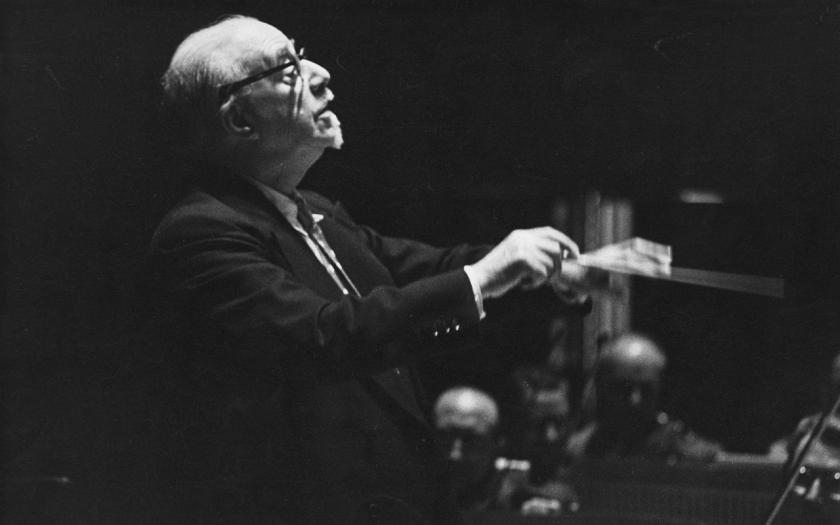

Sir Thomas Beecham: Complete Stereo Recordings on Warner Classics (Warner)

Sir Thomas Beecham: Complete Stereo Recordings on Warner Classics (Warner)

Sir Thomas Beecham’s recording career began way back in 1910, this Warner compilation collecting the stereo LPs he made for EMI between 1955 and 1959. These were his last recordings, made when Beecham was well into his seventies. You'd never know – compare them with the later discs in Warner's Otto Klemperer box, many marred by lumbering tempi and sloppy orchestral playing. This set's contents fill 35 CDs, which gives a hint as to how active Beecham was in the studio. Look carefully at the session information printed on the back of each sleeve and it's apparent that individual works tended to be stitched together from multiple sessions, often in different venues. Take Beecham’s famous disc of Schubert’s 3rd and 5th Symphonies, recorded with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra between May and December 1958 in Paris’s Salle Wagram and London’s Abbey Road Studios. The joins don't show.

David Patmore’s sleeve note relates that when EMI signed Beecham in the mid-1950s they were largely content to let him record whatever he wanted. You can sense that in most of these performances: everyone seems to be having a good time. Beecham’s own Royal Philharmonic were in very good shape, the wind and brass playing especially stylish, and having the Orchestre National de la Radiofusion Française on hand meant that the albums of French music sound particularly idiomatic. A 1959 account of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique has more pep than many a modern recording, and there’s an effervescent coupling of Bizet’s then-recently rediscovered Symphony in C and Lalo’s Symphony in G minor, no masterpiece but an entertaining work. I first heard Franck’s Symphony in D minor via Beecham’s Paris version, and it’s coupled here with Fauré’s Dolly and the first orchestral suite from Bizet’s Carmen. The sessions for a famous set of the complete opera with Victoria de los Ángeles took place more than a year apart – again, you’d never suspect.

David Patmore’s sleeve note relates that when EMI signed Beecham in the mid-1950s they were largely content to let him record whatever he wanted. You can sense that in most of these performances: everyone seems to be having a good time. Beecham’s own Royal Philharmonic were in very good shape, the wind and brass playing especially stylish, and having the Orchestre National de la Radiofusion Française on hand meant that the albums of French music sound particularly idiomatic. A 1959 account of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique has more pep than many a modern recording, and there’s an effervescent coupling of Bizet’s then-recently rediscovered Symphony in C and Lalo’s Symphony in G minor, no masterpiece but an entertaining work. I first heard Franck’s Symphony in D minor via Beecham’s Paris version, and it’s coupled here with Fauré’s Dolly and the first orchestral suite from Bizet’s Carmen. The sessions for a famous set of the complete opera with Victoria de los Ángeles took place more than a year apart – again, you’d never suspect.

Beecham’s Haydn holds up well, seven late symphonies included here. There’s a lively The Seasons, in an English translation. There’s a generous Mozart selection including a complete Die Entführung aus dem Serail, though I’m drawn to a stylish 1957 account of Symphony No.41, one of that CD’s bonus features being part of the symphony’s first movement recorded by EMI in 1934 in experimental stereo. A 1958-59 Beethoven 7 is exhilarating, coupled here with a lively Brahms 2, the finale’s coda bold and brassy. I’d forgotten how exciting Beecham’s Ein Heldenleben is, blessed with ripe horns, flowing speeds and piquant woodwinds. A 1957 Scheherazade is justifiably famous, and there’s more Russian repertoire in the shape of Borodin’s Polovtsian Dances and Balakirev’s charming Symphony No. 1. Plus, frustratingly, just the finale of Tchaikovsky’s 4th Symphony, the one movement taped in stereo – presumably the rest of it will appear in the upcoming mono box.

Beecham’s Haydn holds up well, seven late symphonies included here. There’s a lively The Seasons, in an English translation. There’s a generous Mozart selection including a complete Die Entführung aus dem Serail, though I’m drawn to a stylish 1957 account of Symphony No.41, one of that CD’s bonus features being part of the symphony’s first movement recorded by EMI in 1934 in experimental stereo. A 1958-59 Beethoven 7 is exhilarating, coupled here with a lively Brahms 2, the finale’s coda bold and brassy. I’d forgotten how exciting Beecham’s Ein Heldenleben is, blessed with ripe horns, flowing speeds and piquant woodwinds. A 1957 Scheherazade is justifiably famous, and there’s more Russian repertoire in the shape of Borodin’s Polovtsian Dances and Balakirev’s charming Symphony No. 1. Plus, frustratingly, just the finale of Tchaikovsky’s 4th Symphony, the one movement taped in stereo – presumably the rest of it will appear in the upcoming mono box.

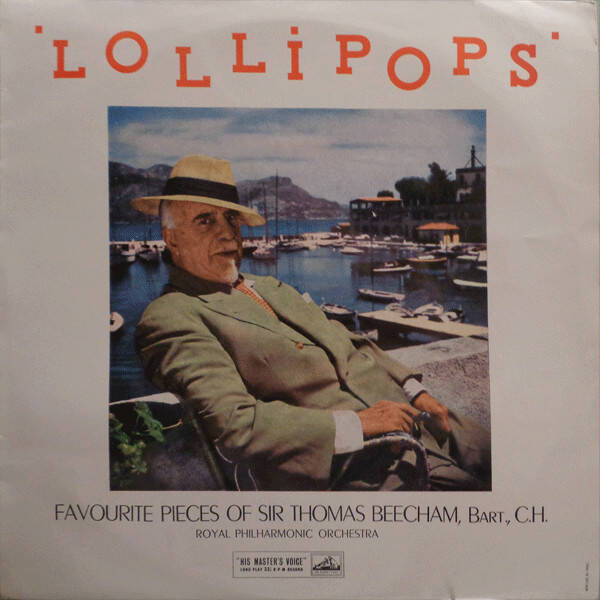

Beecham’s stereo Delius recordings are all here. “Sleigh Ride” is one of my guilty pleasures, and the introductory “Daybreak” at the start of the Florida Suite is irresistible. There’s some decent Sibelius, the tone poems Tapiola and The Oceanides very well done, plus a winning account of the incidental music to Pelléas et Mélisande. Several discs contain a miscellany of shorter pieces, or "lollipops". When was the last time you heard Chabrier’s Joyeuse marche or Saint-Saëns’ tone poem Le Rouet d’Omphale? And marvel at the cover photo, Beecham relaxing with a cigar by a harbour in France, the country where he emigrated to in 1957 for tax reasons. And why doesn’t someone revive Beecham’s Love in Bath and The Gods Go A’Begging, two ballet scores made up mostly of neglected numbers from Handel operas and oratorios, lavishly reorchestrated? Both are great fun and stylishly played. The early stereo recordings still sound good and that some of them are seventy years old is hard to believe. Warners’ box design is a tad gloomy though, Beecham resembling Brando’s Don Corleone in The Godfather. That apart, this is a very desirable package.

Beecham’s stereo Delius recordings are all here. “Sleigh Ride” is one of my guilty pleasures, and the introductory “Daybreak” at the start of the Florida Suite is irresistible. There’s some decent Sibelius, the tone poems Tapiola and The Oceanides very well done, plus a winning account of the incidental music to Pelléas et Mélisande. Several discs contain a miscellany of shorter pieces, or "lollipops". When was the last time you heard Chabrier’s Joyeuse marche or Saint-Saëns’ tone poem Le Rouet d’Omphale? And marvel at the cover photo, Beecham relaxing with a cigar by a harbour in France, the country where he emigrated to in 1957 for tax reasons. And why doesn’t someone revive Beecham’s Love in Bath and The Gods Go A’Begging, two ballet scores made up mostly of neglected numbers from Handel operas and oratorios, lavishly reorchestrated? Both are great fun and stylishly played. The early stereo recordings still sound good and that some of them are seventy years old is hard to believe. Warners’ box design is a tad gloomy though, Beecham resembling Brando’s Don Corleone in The Godfather. That apart, this is a very desirable package.

Lindberg and Aho Clarinet Concertos Julian Bliss (clarinet), BBC Scottish SO/Taavi Oramo (Signum)

Lindberg and Aho Clarinet Concertos Julian Bliss (clarinet), BBC Scottish SO/Taavi Oramo (Signum)

I have been in love with the Magnus Lindberg Clarinet Concerto since I first heard the premiere recording, by its dedicatee and inspiration Kari Kriikku, on its release in 2005. Lindberg had been something of a hardcore modernist in the 1980s and 90s, but this concerto is part of his progression towards a more relaxed, warm and melodic musical language. The concerto teems with orchestral detail, the clarinet at times darting among these textures, sometimes floating deliciously above, sometimes nodding towards Lindberg’s early work with electronics.

There have been a couple of other recordings, in 2019 and 2020, but this new version by Julian Bliss is very much to be welcomed. His solo opening is completely captivating and all the way through he excels in the quiet moments. The orchestra, led by Taavi Oramo, is appropriately delicato in those bits, wispy celesta and percussion, the multiply-divided strings giving a spacious bed to the sound. But the true glory of this piece is in the two tutti eruptions of the big tune, filled with a Gershwin-like Broadway spirit, which Bliss relaxes into, without Kriikku’s urgent joyfulness, but with a swaggering confidence in the music’s ability to stay airborne. The BBC Scottish are clean and precise, with the woodwind, so artfully scored, particularly good. But the star is obviously Bliss himself, whose playing in the cadenza – his own, not the composer’s original – is truly dazzling, and fully in keeping with the spirit of the piece.

By contrast with the Lindberg, a longstanding favourite, the concerto by fellow Finn Kalevi Aho was new to me. It dates from about the same time, and was commissioned by another great of the modern clarinet, Martin Fröst. And like the Lindberg, Aho’s extended piece is in one uninterrupted movement with an extended solo cadenza. There the similarities end. The start is punchy and assertive, Bliss driving things forward, which soon gives way to a more meditative passage, simplicity itself. Aho’s orchestration doesn’t have the infinite detail of Lindberg but in lots of ways his piece is more direct, and Bliss’s playing reflect that. The fourth section, “Adagio mesto”, is the heart of the piece and, for all its hyperactivity elsewhere, this is the bit that sticks in the memory, heartfelt and poised and very beautiful. - Bernard Hughes

Seasons in Moominvalley Lauri Porra (Sony)

Seasons in Moominvalley Lauri Porra (Sony)

Tove Jansson’s sequence of Moomin novels are a beguiling mixture of comfort and chills, the final two instalments very bleak indeed. Listening last week to Thomas Adés conducting a suite from Sibelius’s incidental music to The Tempest at the BBC Proms had me wondering what Moomin-inspired music by the great Finnish composer might have sounded like. Jansson’s first instalment was published 80 years ago, when Sibelius was still very much alive, though his creative career was all but over. So it feels fitting that this album has just been released, its 21 short tracks composed by bass guitarist-turned composer Lauri Porra, Sibelius’s great-grandson. Variously scored for solo piano and a small string ensemble, each number takes inspiration from a scene from the books.

The more introspective pieces are the ear-ticklers, Porra’s music often augmented by field recordings of wind, water and birdsong. Try “The Deep Part of the Forest”: two minutes of affecting ambient wooziness, sustained string chords and bird calls, underpinned by Porra’s electric bass. Or “A Song for Autumn”, pianist Antti Kujanpää and violinist Kasmir Uusitupa illustrating a moment when “you store up your thoughts and burrow yourself into a deep hole inside, a core of safety”. I liked the chilliness of “A Freezing White Mist”, and the handclaps and string slides that punctuate “Trolleyful of Pancakes”. The album is beautifully produced: close your eyes and it’s as if you’re sequestered in a small wood-panelled room, swaddled in a blanket. Sony’s production values are appealing, Jansson’s texts and illustrations reproduced in the booklet.

Ailís Ní Ríain: Holocene Onyx Brass, Hammonds Brass Band (NMC)

Ailís Ní Ríain: Holocene Onyx Brass, Hammonds Brass Band (NMC)

A perk of this gig is enlarging one’s vocabulary, so I now know that the Holocene is ‘is an interglacial period within the ongoing glacial cycles of the Quaternary’. Put simply, it’s the 11,700 years since the last Ice Age, a relatively warm period in the planet’s history between ice ages. Ailís Ní Ríain’s 14-minute Holocene was premiered at Bradford Cathedral in June (where this live recording was made), a New Music Biennial collaboration between Ní Ríain and Onyx Brass, supported by the local Hammonds Band. Listen to this through headphones and you’re made aware of the work’s strata, the busier brass quintet writing playing out over slow-moving, dense slabs of sound. Chords slip in and out of focus, the murky textures periodically broken by chattering trumpets and trombones. It’s akin to witnessing a seismic event in slow motion, a doleful close with a handful of instruments gasping for breath suggesting that the future doesn’t look too hopeful. Ní Ríain’s deafness means that she can only hear low frequencies: that Holocene is so viscerally effective suggests that she possesses a remarkable musical imagination. Recommended.

Domenico Scarlatti: Sonatas Javier Perianes (piano) (Harmonia Mundi)

Domenico Scarlatti: Sonatas Javier Perianes (piano) (Harmonia Mundi)

The problem with programming a disc of Scarlatti sonatas – how to choose 15 out of the 550+ available? – fortunately has an easy solution: they are all so good it is impossible to make a duff selection. The back cover boasts that Javier Perianes has put together a “compendium of his most attractive sonatas”, and it’s hard to quibble even in the absence of several favourites. Perianes’s is perhaps a slightly safe choice, without the most wild of Scarlatti’s experiments, and the playing lacks the eccentricity and extremity of Mikhail Pletnev’s, who is my personal touchstone in this repertoire. But there is still plenty to enjoy. I think Scarlatti benefits from being heard on a modern piano more than other baroque masters: lots of the textures are so perfect for the piano it’s hard to remember the instrument was in the future.

Of the pieces here, K.141 is irresistibly virtuosic in its rapidly repeated notes, a particularly pianistic effect, as are the rising left-hand octaves. Equally flamboyant and even more exuberant is K.125, with Perianes’s right-hand semiquavers flowing with seamless legato, also a feature of K.386, with its chromatic adventures. And there is an appropriate finale in K.448, which sounds more like Scarlatti’s exact contemporary Bach than anything else here – they are normally poles apart.

But it isn’t all about display. K.466 is pared-back and played with touching fragility, exploring a three-against-two cross-rhythm that is advanced for the time. Likewise K.462, in the same key of F minor, has a bare two-part texture which belies a depth of expression that Perianes mines without exploiting. Elsewhere the sheer joyful invention is infectious – K.492 twists and turns in a new direction each time it seems to get established, and K.380 trills and bounces along delightfully. This is a nicely sequenced and tastefully played selection, and if it won’t displace Pletnev in my pantheon, it doesn’t have to: the more Scarlatti, the better, there’s plenty to go round. - Bernard Hughes

Schumann: Dichterliebe and Kerner-Lieder, Schubert/Nitschke: Schwanengesang Jonas Kaufmann (tenor), Helmut Deutsch (piano), Claus Guth (director of "dramatized staging" on DVD) (Sony)

Schumann: Dichterliebe and Kerner-Lieder, Schubert/Nitschke: Schwanengesang Jonas Kaufmann (tenor), Helmut Deutsch (piano), Claus Guth (director of "dramatized staging" on DVD) (Sony)

Jonas Kaufmann’s set Doppelgänger has four parts to it. First there is a truly fabulous Dichterliebe recorded in April 2020. Kaufmann and Helmut Deutsch spent a period of nine days in the lakeside town of Herrsching am Ammersee near Munich to record both this cycle and the twelve Schumann settings of poems by Kerner, Op.35. The clarity and purpose in every word of Dichterliebe is just stunning. To hear Kaufmann launch himself into the upper "ossias", the top G in “ganz und gar gesund” in the fourth song and, even better, the exultant top A in “die Schlang", die dir am Herzen frisst” has made my week. I am less sure about Kaufmann’s Kerner cycle. I think I just warm to a deeper, darker voice in these songs, such as Matthias Goerne with his two recordings, with Eric Schneider in 1999, or the way he sank into lower keys 20 years later with Leif Ove Andsnes, and I have an irresistible affection for Martti Talvela with Irwin Gage.

For a fascinating contrast with the new Dichterliebe, there is a previously unissued recording of six songs from the cycle with Kaufmann and pianist Jan Philip Schulze from 1994. Schulze these days has guru status in the highly successful Lied faculty in Hannover. The then-and-now juxtaposition of Kaufmann in the same repertoire in the same keys twenty-six years apart is fascinating, particularly in the way they convey the scale of his dramatic presence in the later recording.

The fourth element of this set is, with apologies to John Cleese, something completely different. It is an 83-minute DVD of a live performance in Wade Thompson Drill Hall in the Park Avenue Armory in New York, made to look like a stylised military hospital, with some 70 beds laid out in neat geometric rows, many of the beds containing dancers acting the parts of war-wounded soldiers. We see a "dramatized staging" of Schubert’s Schwanengesang. The song cycle has been shorn of its final, presumably too optimistic “Taubenpost” but also has some additions: from Schubert we are gifted “Herbst”, another Rellstab setting, and also the ten-minute andante movement of the late B flat piano sonata. Germans do love their Spannungsbögen (arcs of tension) and theatre director Claus Guth put sound artist Mathis Nitschke to the task of binding the songs together with electronic sounds, and to provide “music and soundscapes that take up the harmonic thread of one song and transfer it into that of the next.” And with such additives we move towards a final sequence in which Kaufmann is carried pall-bearer-style in his bed and processed round the room in “Am Meer”, followed by the darkness of “Die Stadt”, to finish with the intensity of “Der Doppelgänger”. It was clearly a powerful and immersive experience in the hall, mainly because Kaufmann and his voice and dramatic presence are at the centre of the action. But, clearly, neither Schubert-as-soundtrack nor Schubert-with-electronic-additives is not going to be to everyone’s taste… - Sebastian Scotney

Verdi: Simon Boccanegra (original 1857 version) Germán Enrique Alcántara (baritone), Eri Nakamura (soprano), Chorus of Opera North, Hallé/Sir Mark Elder (Opera Rara)

Verdi: Simon Boccanegra (original 1857 version) Germán Enrique Alcántara (baritone), Eri Nakamura (soprano), Chorus of Opera North, Hallé/Sir Mark Elder (Opera Rara)

That this is a new recording of a little-known score is not this set’s main selling point. The biggest draw for me is that Opera Rara’s exhumation of Verdi’s 1857 original version of Simon Boccanegra is a studio recording, with all the advantages that brings. It’s idiomatically conducted by Sir Mark Elder, with a strong cast, fulsome orchestral playing, and there’s no stage or audience noise. Based on historical events, Francesco Maria Pave’s libretto is a convoluted tale of 14th century politics, the titular hero’s problems beginning when he’s elected Doge of Genoa in 1339. The opera received mixed reviews when premiered, Verdi remembering it as “a fiasco”. Some years later, his publisher Ricordi prompted him to revise the work with the help of librettist Arrigo Boito. The biggest change was the rewritten Act 2 finale, an intense council chamber scene replacing a more conventional one set in Genoa’s main square. Opera Rara’s Roger Parker, editor of a new Critical Edition, describes the 1857 score as “much sparer, more stylistically coherent… with a completely different attitude to orchestral sonorities.” That original finale, its "Prisoners and African women" aside, is a blast here, with magnificent contributions from the Chorus of Opera North and the RNCM's Opera Chorus. A “Chorus of Women on the Sea” is glorious, the voices imperceptibly growing louder as they get closer, and the entry of the men’s voices in their “Viva Simon!” is spectacular.

Argentinian baritone Germán Enrique Alcántara is a convincing lead, nicely supported by Eri Nakamura as his long-lost daughter Maria. Sergio Vitale has fun as the villainous Paolo, bent on revenge after Amelia turns down his marriage proposal, and Iván Ayón-Rivas is sympathetic as Gabriele, his upper register magnificent. Elder’s enthusiasm is palpable, his Hallé players following every gear change. Verdi’s sombre finale, the poisoned Boccanegra gasping for breath, is deeply moving. Presentation and packaging impress, Opera Rara’s thick booklet including a full libretto plus English translation. The engineering is alluring, the acoustic of Hallé St Peter’s a more sympathetic and immediate-sounding venue than Manchester’s Bridgewater Hall.

The Music Never Ends Vasari Singers/Jeremy Backhouse (Naxos)

The Music Never Ends Vasari Singers/Jeremy Backhouse (Naxos)

In Your Dreams Kantos Chamber Choir/Ellie Slorach (Delphian)

Here’s a double bill of very different choral albums; Kantos Chamber Choir’s programme explores sleep and dreams while the Vasari Singers The Music Never Ends is a fun romp through close-harmony repertoire. They speak to the variety on offer in the choral world at the moment.

Kantos is a professional chamber choir (19 strong on this project) based in the north of England and led here by its founder Ellie Slorach, celebrating its 10th anniversary this year. In Your Dreams started out as a live concert programme, now become a concept album combining music with spoken poetry, all bound together by the topic of sleep and dreams. It is a very winning combination: the (very short) spoken interludes, sound-effects of waking and sleep-talking, jump-cutting from item to item (In Your Dreams very much should be listened to straight through) and the fantastical subject matter all meld together into a powerful artistic statement. The singing is first rate and the recording made with Delphian’s usual care.

Some of the pieces are established in the repertoire: Eric Whitacre’s Sleep was an obvious choice, as was Rheinberger’s Abendlied. Philip Lawson’s arrangement of Billy Joel’s "Lullabye", made for the Kings Singers, perhaps less so, but lets us hear another side of Kantos. They sing lovingly but do not indulge the sentimentality of the song and keep it moving. Of the pieces that explore the nonsensical quality of dreams by far the best is Jaakko Mäntyjärvi’s Pseudo-Yoik, two minutes of crazed chanting in a made-up language. It is difficult to describe but once heard is never forgotten, and this is the best recorded version I’ve heard. On the other hand, I have a bit of an aversion to Mátyas Seiber’s Nonsense Songs on Lear limericks, although they are sung with spirit.

The three previously unrecorded pieces are all very different gems. The opening track is Slorach’s own arrangement of an anonymous setting of Golden Slumbers, which her mother used to sing to her as a child. It is haunting, starting with three voices at a distance and slowly coming into focus for full choir. Kantos sing with confident resonance in Edmund Jolliffe’s rollicking (initially) and noble (later) Be not afeard, while Kristina Arakelyan’s Train Ride is a daydream, eccentric and busy, sung ostinatos alternating with passages of muttering, showcasing the choir’s willingness to take risks in performance.

The three previously unrecorded pieces are all very different gems. The opening track is Slorach’s own arrangement of an anonymous setting of Golden Slumbers, which her mother used to sing to her as a child. It is haunting, starting with three voices at a distance and slowly coming into focus for full choir. Kantos sing with confident resonance in Edmund Jolliffe’s rollicking (initially) and noble (later) Be not afeard, while Kristina Arakelyan’s Train Ride is a daydream, eccentric and busy, sung ostinatos alternating with passages of muttering, showcasing the choir’s willingness to take risks in performance.

The Vasari Singers have been one of London’s leading amateur choirs since the 1980s, always under the leadership of founder Jeremy Backhouse. On The Music Never Ends, the 21 tracks include arrangements by Jonathan Rathbone (former Swingle Singer) and the master himself, Ward Swingle, in songs as varied as “Waltzing Matilda” and “Send in the Clowns”, as well as a handful of original compositions. The arrangements that work best are the Lennon and McCartney ones, while the Shakespeare section left me a bit underwhelmed – George Shearing’s Songs and Sonnets from Shakespeare are disappointingly pedestrian.

If the Vasaris lack the vocal strength and polish of Kantos they are still very good, and clearly revel in this repertoire, taking one-to-a-part arrangements and singing them chorally. The tuning is precise, no matter how involved the harmonic progressions, and choir sets out to characterise the contrasting songs, from the languid richness of Ward Swingle’s Romance, with its lovely baritone solo by Matthew Wood, to the “ba-doo-wah” swing of “Penny Lane”. The album finishes with Jocelyn Somerville’s subtle solo on “Send in the Clowns” followed by an upbeat “It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing” - both show the choir at its best. - Bernard Hughes

Add comment